Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Plateaus in Language Learning and How to Overcome Them

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth. I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth.

I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

I told this nice, patient lady that I was studying Japanese and she asked me how long I was staying in China for. I wanted to tell her I was going back to England next Thursday, but instead I said 先週の水曜日に帰ります (senshuu no suiyoubi ni kaerimasu) - "I'll go back last Wednesday."

OOPS.

I think about this day quite a lot because it shows, I think, that although I'd studied lots of Japanese at that point my communicative skills were pretty poor. I considered myself an intermediate learner, but I couldn't quickly recall the word for Wednesday, or the word for last week.

I realised at that point that I hadn't made much real progress in the last two years. The first year I zipped along, memorising kana and walking around my house pointing at things saying "denki, tsukue, tansu" (lamp, desk, chest of drawers) But after that my Japanese had plateaued.

So, I started actively trying to speak - I took small group lessons, engaged in them properly, did the prep work. I wrote down five sentences every day about my day and had my teacher check them. I met up with a Japanese friend regularly and did language exchange - he corrected my grammar and told me when I sounded odd (thanks, Kenichi!)

(Most of this happened in Japan, but like I said, you don't need to live in Japan to learn Japanese.)

And I came out of the plateau. I set myself a concrete goal - to pass the JLPT N3. The JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) is a standardised test in Japanese, for non-native speakers. N3 is the middle level - intermediate.

Once I’d passed that, I started aiming for N2, the next level up. I had some job interviews in Japanese, a terrifying and fascinating experience.

I wanted to get a job with a Board of Education, and a recruiter told me you needed N1 - the highest level of the JLPT - for that, so I started cramming kanji and obscure words. I was back on the Japanese-learning train.

I didn't pass N1 though, not that time.

And I was bored of English teaching and didn't want to wait to pass the test before I got a job using Japanese - that felt a bit like procrastinating - so I quit my English teaching job and got a job translating wacky entertainment news.

And after six months translating oddball news I passed the test.

That's partly because exams involve a certain amount of luck and it depends what comes up. But I also believe it's because using language to actively do something - working with the language - is a much, much better way of advancing your skills than just "studying" it.

Thanks to translation work, I was out of the plateau again. Hurrah!

When you're in the middle of something - on the road somewhere - it's hard to see your own development.

Progress doesn't move gradually upwards in a straight line. It comes in fits and starts.

Success doesn't look like this:

It looks like this:

And if you feel like you're in a slump at the moment, there are two approaches.

One is to trust that - as long as you're working hard at it - if you keep plugging away, you'll suddenly notice you've jumped up a level without even realising. You're working hard? You got this.

The other approach is to change something. Make a concrete goal. Start something new. Find a new friend to talk to or a classmate to message in Japanese. Talk to the man who owns the noodle shop about Kansai dialect. Write five things you did each day in Japanese. Take the test. Apply for the job. がんばる (gambaru; “try your best”).

Originally posted February 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

Why Does The Japanese Language Have So Many Alphabets?

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

Until the 1st or 2nd century, Japan had no writing system. Then, sometime before 500AD, kanji - Chinese characters - made its way to Japan from China (probably via Korea).

These characters were originally used for their meaning only - they weren't used to write native Japanese words.

↓ And at that time, Japanese writing looked like this. Look, it looks like Chinese!

(Image Source - Nihon Shoki, Wikipedia)

But it was inconvenient not being able to write native Japanese words down, and so people began to use kanji to represent the phonetic sounds of Japanese words, not only the meaning. This is called manyougana and is the oldest native Japanese writing system.

For example, in manyougana the word asa (morning) was written 安佐 (that's a kanji for the “a” sound - 安 - and another for the “sa” sound - 佐). These characters indicate the sound of the word - “asa” - but not its meaning.

In modern Japanese we'd use 朝, the kanji that means "morning" for asa. This character shows its meaning AND its sound.

The problem was, manyougana used multiple kanji for each phonetic sound - over 900 characters for the 90 phonetic sounds in Japanese - so it was inefficient and time-consuming.

Gradually, people began to simplify kanji characters into simpler characters - that's where hiragana and katakana came from.

Katakana means "broken kana" or "fragmented characters". It was developed by monks in the 9th century who were annotating Chinese texts so that Japanese people could read them. So katakana was really an early form of shorthand.

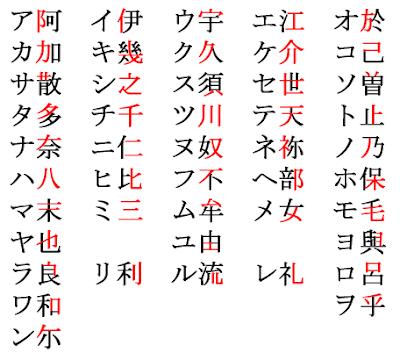

Each katakana character comes from part of a kanji: for example, the top half of the kanji 呂 became katakana ロ (ro), and the left side of the kanji 加 became katakana カ (ka).

↓ Each katakana comes from part of a kanji.

(Source - Katakana origins, Wikipedia)

Women in Japan, on the other hand, wrote in cursive script, which was gradually simplified into hiragana. That's why hiragana looks all loopy and squiggly. Like katakana, hiragana characters don't have meaning - they just indicate sound.

↓ How kanji (top) evolved into manyougana (middle in red), and then hiragana (bottom).

(Source - Hiragana evolution, Wikipedia)

Because it was simpler than kanji, hiragana was accessible for women who didn't have the same education level as men. The 11th-century classic The Tale of Genji was written almost entirely in hiragana, because it was written by a female author for a female audience.

Modern Japanese writing uses all three of these “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji - often all mixed up in the same sentence.

What would 12th-century people in Japan think of my students, 900 years later, learning hiragana as they take their first steps into the Japanese language?

First published 28th Oct 2016

Updated 27th Jan 2020

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.