Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Plateaus in Language Learning and How to Overcome Them

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth. I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth.

I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

I told this nice, patient lady that I was studying Japanese and she asked me how long I was staying in China for. I wanted to tell her I was going back to England next Thursday, but instead I said 先週の水曜日に帰ります (senshuu no suiyoubi ni kaerimasu) - "I'll go back last Wednesday."

OOPS.

I think about this day quite a lot because it shows, I think, that although I'd studied lots of Japanese at that point my communicative skills were pretty poor. I considered myself an intermediate learner, but I couldn't quickly recall the word for Wednesday, or the word for last week.

I realised at that point that I hadn't made much real progress in the last two years. The first year I zipped along, memorising kana and walking around my house pointing at things saying "denki, tsukue, tansu" (lamp, desk, chest of drawers) But after that my Japanese had plateaued.

So, I started actively trying to speak - I took small group lessons, engaged in them properly, did the prep work. I wrote down five sentences every day about my day and had my teacher check them. I met up with a Japanese friend regularly and did language exchange - he corrected my grammar and told me when I sounded odd (thanks, Kenichi!)

(Most of this happened in Japan, but like I said, you don't need to live in Japan to learn Japanese.)

And I came out of the plateau. I set myself a concrete goal - to pass the JLPT N3. The JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) is a standardised test in Japanese, for non-native speakers. N3 is the middle level - intermediate.

Once I’d passed that, I started aiming for N2, the next level up. I had some job interviews in Japanese, a terrifying and fascinating experience.

I wanted to get a job with a Board of Education, and a recruiter told me you needed N1 - the highest level of the JLPT - for that, so I started cramming kanji and obscure words. I was back on the Japanese-learning train.

I didn't pass N1 though, not that time.

And I was bored of English teaching and didn't want to wait to pass the test before I got a job using Japanese - that felt a bit like procrastinating - so I quit my English teaching job and got a job translating wacky entertainment news.

And after six months translating oddball news I passed the test.

That's partly because exams involve a certain amount of luck and it depends what comes up. But I also believe it's because using language to actively do something - working with the language - is a much, much better way of advancing your skills than just "studying" it.

Thanks to translation work, I was out of the plateau again. Hurrah!

When you're in the middle of something - on the road somewhere - it's hard to see your own development.

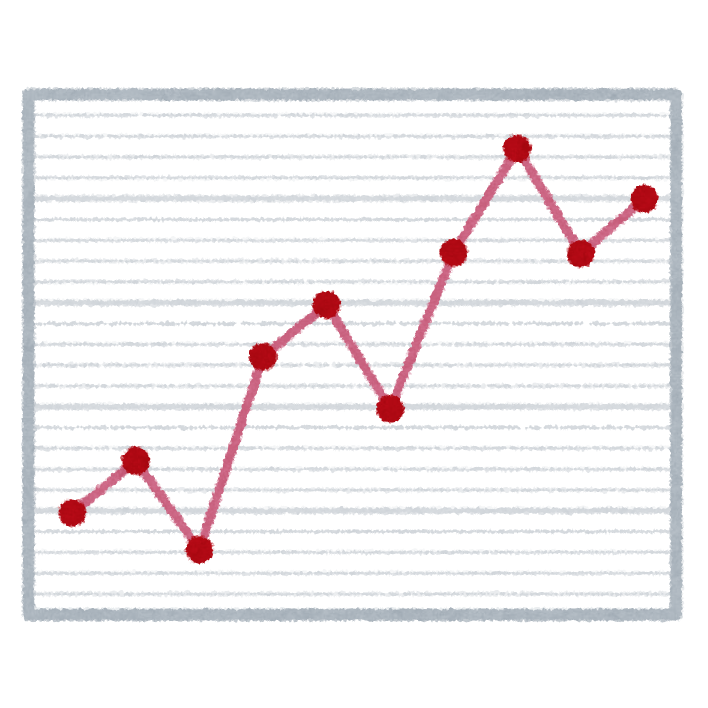

Progress doesn't move gradually upwards in a straight line. It comes in fits and starts.

Success doesn't look like this:

It looks like this:

And if you feel like you're in a slump at the moment, there are two approaches.

One is to trust that - as long as you're working hard at it - if you keep plugging away, you'll suddenly notice you've jumped up a level without even realising. You're working hard? You got this.

The other approach is to change something. Make a concrete goal. Start something new. Find a new friend to talk to or a classmate to message in Japanese. Talk to the man who owns the noodle shop about Kansai dialect. Write five things you did each day in Japanese. Take the test. Apply for the job. がんばる (gambaru; “try your best”).

Originally posted February 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

"How Did You Learn Japanese?"

When I tell people I'm a Japanese teacher they quite often ask: how did you learn Japanese? And I don't find this question particularly easy to answer.

Sometimes I give a quick answer which is that I used to live there.

But you can live in Japan for years and not learn Japanese.

I've met lots of people like this (and there's nothing wrong with that, unless learning Japanese is the reason you moved to Japan).

The long and more honest answer to "how come you speak Japanese?":

When I tell people I'm a Japanese teacher they quite often ask: how did you learn Japanese? And I don't find this question particularly easy to answer.

Sometimes I give a quick answer which is that I used to live there.

But you can live in Japan for years and not learn Japanese.

I've met lots of people like this (and there's nothing wrong with that, unless learning Japanese is the reason you moved to Japan).

The long and more honest answer to "how come you speak Japanese?" is that I studied a bit in university, then studied a LOT in my free time, got slightly obsessed with kanji, spent a lot of time with Japanese-speaking friends, avoided English-only situations and people who wanted to learn English from me for free, took all the JLPTs, went to Japanese language school full-time for a bit, read books and manga and newspapers (even when I couldn't read them yet), and watched a lot of Japanese TV.

You don't need to be in Japan to do any of those things:

listen to Japanese audio all day

learn kanji on the bus (with Anki. Use anki. I wrote a post about that too)

find friends who speak Japanese

watch Japanese TV on Netflix (seriously, there's loads)

Being in Japan was great motivation to learn Japanese for me because I hate not understanding things and find it incredibly frustrating.

If you're in Japan and you want to know what's in your lunch or what that sign over there says or what the person next to you on the train is saying, you need to understand Japanese. That was a big push for me.

But you definitely don't need to live in Japan to get motivated.

I also started off working in English conversation school which was a good opportunity to listen to the kind of Japanese that five-year-olds speak. And one of the many good things about conversation school is you have the mornings off so I would get up and STUDY. Every day. Forever.

But I also probably have more free time now than I did in Japan.

You don't need to live in Japan to learn Japanese.

There are people all over the world who learn languages without living in the country the language comes from. I've met lots of people like this and had the pleasure of teaching some of them.

(The other thing I tell people when they ask how I learned Japanese is that I didn't learn it. I'm still learning.)

First published 17th Feb 2017

Updated 2nd March 2020

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

"Kyūkei shimashou" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called kyūkeijo 休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to strike up a conversation …

"

Ky

ū

kei shimashou

" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called

kyūkeijo

休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to

.

Luckily for me, the bit of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail I walked this spring had interesting and varied rest stops throughout. So what kind of places are used as

kyūkeijo

?

1) Temple outbuildings

On the first day I walked with another pilgrim, who I'd met at temple number 1. We stopped around midday, at a

ky

ū

keijo

in a temple outhouse building.

The women inside offered us tea and sweets, and in exchange we handed them

osamefuda

(納め札),

slips of paper with your name and a message, on which pilgrims carry instead of money

.

(...traditionally, I mean. Most modern pilgrims carry money too now.)

I was grateful to receive the tea and sweets, but even more grateful to have the opportunity to chat with these friendly women, who said they had lived in Shikoku all their lives.

They told me their ages (in their 70s and 80s), and that some of them had walked the 750-mile pilgrimage three or four times in their lifetimes.

2) Private houses

Some rest stops are out the front of a private home. The owners prepare tea or hot water each morning, and leave it out for visiting walkers:

I sat at this one alone and ate my packed lunch. It was a baking hot day, so I was glad to be out of the sunshine.

Both these

ky

ū

keijo

had signs explaining that the snacks and drinks are offered for free as

o-settai

(お接待), small gifts given to walking pilgrims to help them on their way.

3) Vending-machine seating

Usually, at the temple itself there will be a vending machine or two, with seating next to it.

It can be seen as impolite to eat or drink while walking in Japan, so vending machines often have seats next to them.

You can enjoy your snack first, and then walk around afterwards. Remember, rest is important!

I sat at this one and had a can of iced coffee:

I also spotted this set of hardwood chairs in one temple rest area, which look like they're set up to accommodate a whole coach trip:

4) Outdoor rest stops

In the mountains, a clearing with a place to sit down can be a really nice surprise. This one below had obviously taken some work to create, being in the middle of the forest. And it was labeled (in English!) as a "lounge", which I thought was just great.

It clearly is a lounge. It just happen to be outside!

5) Wooden huts

There are also small rest houses maintained by community groups. These are good for getting out of the sun (or the rain!)

This one had a formidable list of rules about not leaving rubbish behind, and stating that it was only for the use of walking pilgrims. It was on a main road in a town, so I guess they'd had problems before.

Anyway, it seems the rules are being followed these days, as the house was spotless:

I had some tea and a delicious fresh orange, read the extensive rules, and wrote in the guestbook.

Towards the end of my walk, I spotted another outdoor rest stop. This one was also purpose-built, with concrete table and seating, and a great view.

What I liked was that people had added extra seating - the sofa and chair, presumably from someone's home:

But the best type of rest stop is when you get to your lodging for the night, and can put your feet up.

それでは、休憩しましょう!

Sore dewa, kyūkei shimashou!

So,

let's take a break!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move. They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly …

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move.

They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly. I waved the little grey bag with its digital camera inside. "

KAMERA

!"

I still couldn't make out their faces, but I thought I saw a glimmer of recognition. One of the pair walked towards me, and it was only then that I saw her face.

"I thought you were Japanese," she said, and I heard a European accent I couldn't place.

"I thought

you

were Japanese," I said.

"We're French," she offered.

"Ah." I paused. "Um, bonjour?"

We walked together a little bit, and then I left them at a rest stop.

I bumped into them again later in the week, at breakfast in the inn we were staying at. The women was showing the owner a piece of paper, and he was squinting at it.

They seemed to be having some difficulty, so I offered to help.

I squinted at the piece of paper too, and was suddenly transported back to year 6, learning about French cursive in class.

There was the name of a youth hostel in the next town over, and a short message underneath. It was all in romaji (Japanese written in the roman alphabet), but in looping, cursive letters:

futari desu. kyou, yoyaku onegai shimasu.

"For two people. A reservation for tonight, please."

I read it aloud to the owner, who promptly got on the phone and made a reservation for them.

"Your note was fine," I told them. "I think he just didn't have his glasses."

Or perhaps he couldn't read their cursive? I didn't say that though.

I wondered later how the rest of their trip went. They seemed to be having a great time.

There's no right or wrong way to walk the Shikoku pilgrimage. And it's possible to travel in Japan without any Japanese language at all. But if you can learn even a bit of the language, you'll have a richer experience, I think.

And you'll understand when someone's trying to tell you you've dropped your camera.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

On walking, and creativity

There are two reasons I like to walk.

The first is that if something is bothering me, I usually find it impossible to be annoyed about it once I have been walking for about half an hour.

You might think that's just because the irritating person or thing is now half an hour away from me.

And that's true. But I think it's something deeper than that, too.

There's something about …

There are two reasons I like to walk.

The first is that if something is bothering me, I usually find it impossible to be annoyed about it once I have been walking for about half an hour.

You might think that's just because the irritating person or thing is now half an hour away from me.

And that's true. But I think it's something deeper than that, too.

There's something about movement, and being outside, that forces my brain to think about things differently.

Maybe

I

was in the wrong?

Or maybe they

are

being unreasonable, but there's nothing I can do about that, and that's ok?

Everything seems better after a half hour walk.

The second reason I like to walk is that's when inspiration seems to strike.

Or to put it another way, I find it almost impossible to be creative while sitting at my desk.

The idea of a

course had been rumbling around in my head for a while, but it formed itself into something concrete when I was in Shikoku in April.

I was surrounded by all these

, and reading constantly. It made me think back to the first time I visited Japan, in 2008. I couldn't read

anything

then, and it was so frustrating.

By the end of the day, I had a clear idea in my head of what I wanted the Survival Japanese course to look like - a practical class, all about getting around.

And an explicit invitation to students to be pro-active and selective about what they need to learn, and what they don't.

I wasn't trying to plan a course on my walk. I was on holiday! I was supposed to be resting my brain, and definitely not working...

But don't you ever find that ideas pop up when you're relaxed, physically away from your work space, and thinking about something else?

This can be annoying. My office isn't at the beach, and I can't take my computer with me on a walk. (You could get out your smartphone, I suppose, and start making notes. But that's not really in the spirit of the thing.)

The writing-things-down part has to happen at my desk. But the thinking part - that usually happens on a walk.

I suspect I'm not the only one. Am I?

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

"Gambatte kudasai" is sort of untranslatable but also extremely translatable. (The best kind of Japanese phrase!)

Gambatte kudasai means "do your best!" or "go for it!"

When I started learning Japanese at university in 2008, my classmates and I thought the phrase gambatte kudasai was quite funny for some reason ...

"Gambatte kudasai"

is sort of untranslatable but also extremely translatable. (The best kind of Japanese phrase!)

Gambatte kudasai

means

"do your best!"

or

"go for it!"

When I started learning Japanese at university in 2008, my classmates and I thought the phrase

gambatte kudasai

was quite funny for some reason. So when we had to write a short dialogue about a holiday and commit it to memory as part of a speaking test, my partner and I shoehorned in a bunch of "

gambatte kudasai"s.

My partner showed our work to his (Japanese) mum, who sent it back covered in red corrections and with all our "

gambatte kudasai

"s crossed out. Apparently they didn't work in context.

The problem is, I knew that

gambatte kudasai

means "try your best", but I didn't know it sounds weird if you're talking about buying a plane ticket...

I heard lots of "

gambatte kudasai"

walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage this spring. It was written everywhere too - in fact there were lots of interesting signs.

The pilgrimage trail is pretty well marked. Signage is consistently spaced, and in many places there's a way-marker every 100 metres.

But it's also endearingly inconsistent in design - on some stretches every sign is different, and many are handmade.

There are these little

aruki-henro

(歩き遍路

;

walking pilgrims) to mark the way:

Red is the dominant colour - sometimes just a red arrow, like this stone below. Actually, there's kanji (Chinese characters) carved into the stone too, but it's difficult to see:

Some signs are in English as well as Japanese, although this was less common:

Some show you which way to turn at an upcoming junction. This took a bit of getting used to, but was very useful. Even in rural areas, I didn't get lost once.

Sometimes, the signs just said 道しるべ (

michi-shirube;

guidepost).

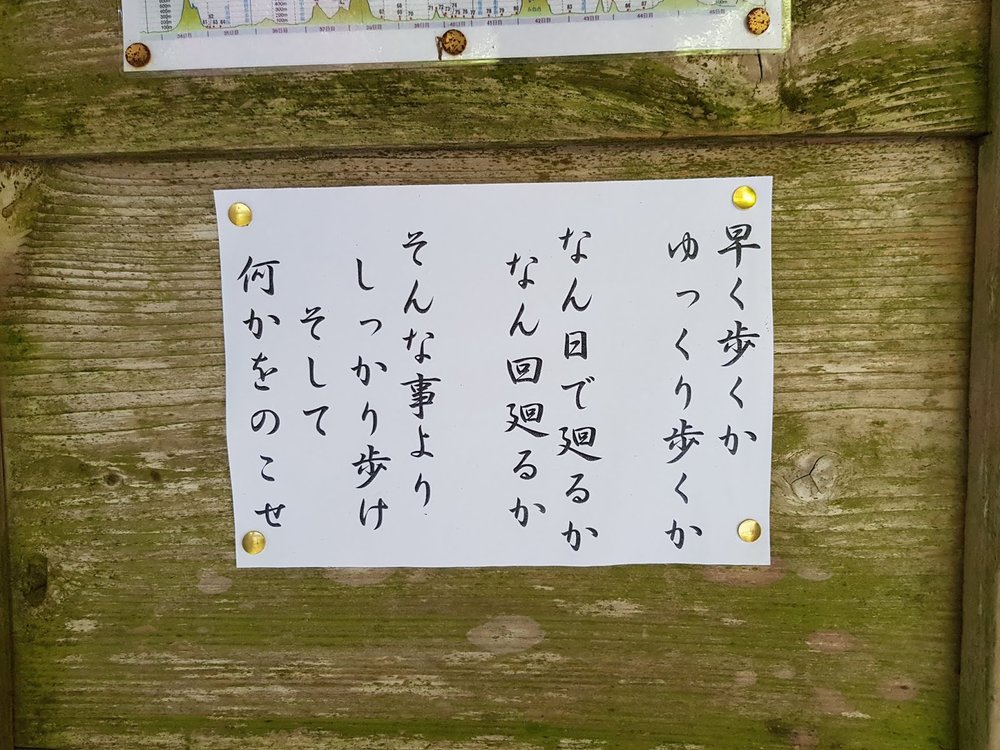

Note that many of these handwritten signs are in vertical text, and from right to left:

This next sign packs a lot of meaning into a few kanji characters:

空海

kūkai

(aka Kōbō Daishi, the Buddhist monk in whose footsteps pilgrims walk)

遍路道

henro michi

(pilgrimage trail)

同行二人

dougyou ni-nin

("two people going together" - the idea that the walking pilgrim is never alone, as Kōbō Daishi is walking with you)

The tough parts of the trail are called

henro korogashi

(遍路ころがし; "the place where the pilgrim falls down").

This bit of

henro korogashi

had even more signposts throughout, so you know how far you have left to go. There's a 1/6 sign to let you know when you are one-sixth of the way through; then 2/6 for two-sixths, and so on.

This picture was taken just before the last stretch, when I was a bit tired:

And of course there are plenty of little signs saying がんばって下さい

gambatte kudasai

(

"keep going!"

.

This made me smile, and was genuinely quite encouraging.

We all need a bit of encouragement sometimes!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

P.S.

If you can't read Japanese, but you want to recognise common signs and notices before your holiday to Japan, you should check out my new

Survival Japanese for Beginners

-

, it starts Thursday 26th July in central Brighton.

Or if you do read Japanese but want to get better, join us for

- a summer course in learning Japanese by reading lots of easy books.

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

A stranger, they say, is just a friend you haven't met yet.

And talking to strangers is a great way to speak lots of Japanese. I did lots of this while walking the first section of the Shikoku pilgrimage this spring.

But how do you start a conversation with a stranger? Here are some ideas to get you going, even if you're a beginner at Japanese.

1) the weather

Brits love to talk about the weather. Luckily, so do people in Japan. It's almost like a greeting.

Chuck one of these out and start the conversation:

暑いですね atsui desu ne! "Hot, isn't it?"

寒いですね samui desu ne! "Cold, isn't it?"

Very possibly, you'll get a そうですね sou desu ne; "Isn't it just", in response, and you can start the conversation from there.

2) things you can see

You reach the top of a hill and sit on a bench. The person on the adjacent seat turns to greet you.

You can start a conversation easily by simply pointing and commenting on what you can see:

すごいですね Sugoi desu ne. "Amazing, isn't it?"

綺麗ですね Kirei desu ne. "Isn't it lovely?"

美しいですね。Utsukushii desu ne. Beautiful, isn't it?

3) ask simple questions

What about if you don't know what you're looking at? Just ask.すみませんが、それはなんですか。 Sumimasen ga, sore wa nan desu ka.

"Excuse me, but what's that?"

これは日本語でなんと言いますか。 Kore wa nihongo de nan to iimasu ka. "What do you call this in Japanese?"

4) start in Japanese

If your Japanese is limited, and you speak English, it might be tempting to walk into a hotel or restaurant and start the conversation in English - or to ask if the person speaks Japanese.Even if you're a beginner, try and start the conversation in Japanese, with a greeting:

こんにちは! konnichiwa! "hello"

こんばんは! kombanwa! "good evening"

おはようございます! ohayou gozaimasu! "good morning"

Remember, if you start the conversation in English (or another language), the chances of getting some Japanese practice are virtually zero. Try and at least start in Japanese.

5) smile

You might be nervous about speaking Japanese. But the absolute best way to get someone to speak with you is to smile while talking with them!

Hopefully, you can put them at ease that you're a friendly, wonderful person. Someone worth talking to. Which, of course, you are.

After all, you're just a friend they haven't met yet too.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

P.S. If you liked this post on talking to strangers in simple Japanese, check out my new course Survival Japanese for Beginners - starts July 26th 2018, in central Brighton. It's ideal for anyone planning a trip to Japan soon!

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.