Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Are Loanwords "Real" Japanese?

Shortly after I started studying Japanese at university, I got an email from a friend in Sweden:

“How’s it going? Learned any more ‘Japanese words’ like camera and video?”

I’d copy-pasted her some of the "new words" from my textbook. There was a list of them - words like kamera (camera) and rajio (radio)…

I felt like I was cheating. These aren’t Japanese words!

Or are they?

Shortly after I started studying Japanese at university, I got an email from a friend in Sweden:

“How’s it going? Learned any more ‘Japanese words’ like camera and video?”

I’d copy-pasted her some of the "new words" from my textbook. There was a list of them - words like kamera (camera) and rajio (radio)…

I felt like I was cheating. These aren’t Japanese words!

Or are they?

Japanese has LOADS of these loanwords - words borrowed from other languages. And two things often happen when a foreign word gets used as a loanword:

Extra vowel sounds

All Japanese syllables - except ん (n) - end in a vowel sound. That means when we convert a foreign word into Japanese, some rogue vowels get thrown in there too:

hot dogホットドッグ hotto doggu

world cup ワールドカップ waarudo kappu

2. Abbreviations

Adding in all those extra vowels makes these loanwords in Japanese much longer than their English equivalents, so they often get shortened:

suupaamaaketto スーパーマーケット

↓

suupaa スーパー (supermarket)

depaatomento sutoa デパートメントストア

↓

depaato デパート (department store)

↓ Spot the katakana loanword(s)!

Sometimes the first bit of both words gets used:

dejitaru kamera デジタルカメラ

↓

dejikame デジカメ (digital camera)

paasonaru konpuuta パーソナルコンピュータ

↓

pasokon パソコン (personal computer)

...which I hope you'll agree are some of the most adorable words ever.

These loanwords, therefore, can teach us a bit about Japanese pronunciation, as well as the Japanese love of abbreviations. I was wrong about them not being "Japanese words", though - depaato and pasokon are definitely Japanese words. Japan may have borrowed them, but it's not giving them back.

Is learning loanwords cheating? What's your favourite Japanese loanword? Let me know in the comments!

First published December 2015

Updated December 7, 2018

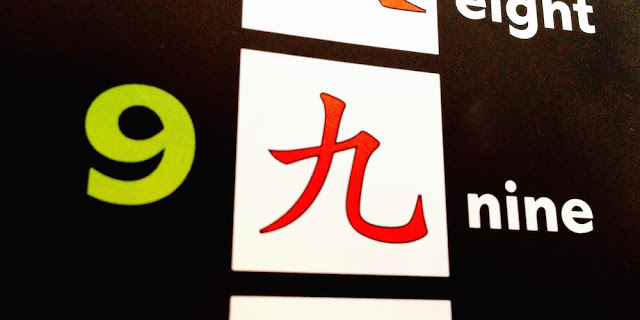

Is it Nana or Shichi? A Brief Introduction to Japanese Numbers

Counting 1-10 should be easy, right?

“Ichi, ni, san, yon... (or is it shi?), go, roku, nana (or shichi), hachi, kyuu (but sometimes ku)...”

Oh, yeah...Japanese has multiple words for the same number! Seven can be either "nana" or "shichi", for example.

So how do you know which word to use?

Sometimes, either is fine – like when you count 1-10, for example. But sometimes, only one word will do.

Let's take a look at some of those special cases.

Counting 1-10 should be easy, right?

“Ichi, ni, san, yon... (or is it shi?), go, roku, nana (or shichi), hachi, kyuu (but sometimes ku)...”

Oh, yeah...Japanese has multiple words for the same number! Seven can be either "nana" or "shichi", for example.

So how do you know which word to use?

Sometimes, either is fine – like when you count 1-10, for example. But sometimes, only one word will do.

Let's take a look at some of those special cases.

FOUR - yon / shi / yo

Yon is used in ages:

よんさい yonsai four years old

and in big numbers:

よんじゅう yonjuu 40

よんひゃく yonhyaku 400

よんせん yonsen 4,000

よんまん yonman 40,000

But you have to use shi for the month:

しがつ shigatsu April

And there’s yo, too, occasionally. Think of it as an abbreviated "yon":

よじ yoji 4 o’clock

よにん yo’nin four people

SEVEN - nana / shichi

Nana is also used in ages:

ななさい nanasai 7 years old

...and in big numbers:

ななじゅう nanajuu 70

ななひゃく nanahyaku 700

ななせん nanasen 7,000

ななまん nanaman 70,000

But shichi must be used in the month AND the o’clock:

しちがつ shichigatsu July

しちじ shichiji 7 o’clock

NINE - kyuu / ku

Nine is usually kyuu, but a notable exception is:

9時くじ kuji nine o’clock

When is a one not a one? When it’s January

So why does Japanese have multiple words for the same number?

It's partly to do with superstition - “shi” sounds like the Japanese word for death and “ku” can mean suffering; “shichi” can also mean “place of death”.

But actually, most languages have multiple words for numbers. We have this in English, too:

1st is “first” (not “one-th”)

The first month of the year is “January” (not “month one”)

Practice makes perfect

Once you've learned which number word to use when, the next step is to practise until they stick!

Anyway, I hope these examples have demystified Japanese numbers for you a little bit. How do you like to practise numbers?

This blog post started life as the answer to a question in one of my Japanese classes (back in 2015!) If you have a question you can't find the answer to, please let me know in the comments or on Facebook / Twitter.

First published November 2015

Updated 27th January, 2019

"I treasure this pen case"

“I treasure this mechanical pencil.”

(Applause)

One of the interesting things about working as an Assistant Language Teacher (ALT) in Japan is that you get to see the kind of English taught in Japanese state schools.

Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s bad; but in my opinion it’s always interesting, and you’re always learning something …

“I treasure this mechanical pencil.”

(Applause)

One of the interesting things about working as an Assistant Language Teacher (ALT) in Japan is that you get to see the kind of English taught in Japanese state schools.

Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s bad; but in my opinion it’s always interesting, and you’re always learning something.

I worked as an ALT for a year in Nagoya, before I started teaching and translating Japanese.

On this particular day I was scheduled to be in class with 13 and 14-year-olds who were giving speeches about a special personal item. The Japanese teacher of English wanted the native English speaker (that’s me!) to assess the kids’ speaking.

I quite liked helping out with speaking assessments - most students enjoy it, and their talks were often funny and creative.

This day was a bit different, though. As the students started to give their talks, I realised all the speeches ended in the same, slightly odd, distinctive phrase:

“I treasure this mechanical pencil.”

“I treasure this eraser.”

“I treasure this pen case.”

(ペンケース (pen keesu), incidentally, is a perfectly good Japanese loanword, but it’s not the English word for “pencil case”, or not where I’m from anyway).

I looked at the textbook. The example from their textbooks was a boy talking about an ice hockey jersey his father had given him, and ended with “I treasure this jersey.”

Ah.

A large number of the students had either:

1) not understood that they were supposed to choose a special and important possession

or

2) forgotten to do the assignment altogether, and hastily cobbled together a speech based on an stationery item they had nearby.

Incidentally, the Japanese translation in their textbook for “I treasure this jersey” (a fairly uncommon English phrase, I’d say) is このジャージを大切にしています (kono jaaji wo taisetsu ni shite imasu).

〜を大切にします (_____wo taisetsu ni shimasu) is a nice, natural sounding way to say you care about or value something in Japanese:

持ち物を大切にする mochimono o taisetsu ni suru - to look after your belongings

体を大切にして下さい karada o taisetsu ni shite kudasai - please take care of yourself

So, at least I learned some Japanese that day, even if I had to sit through thirty speeches about treasured erasers.

What’s your treasure? I’ll tell you about mine next week!

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.