Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

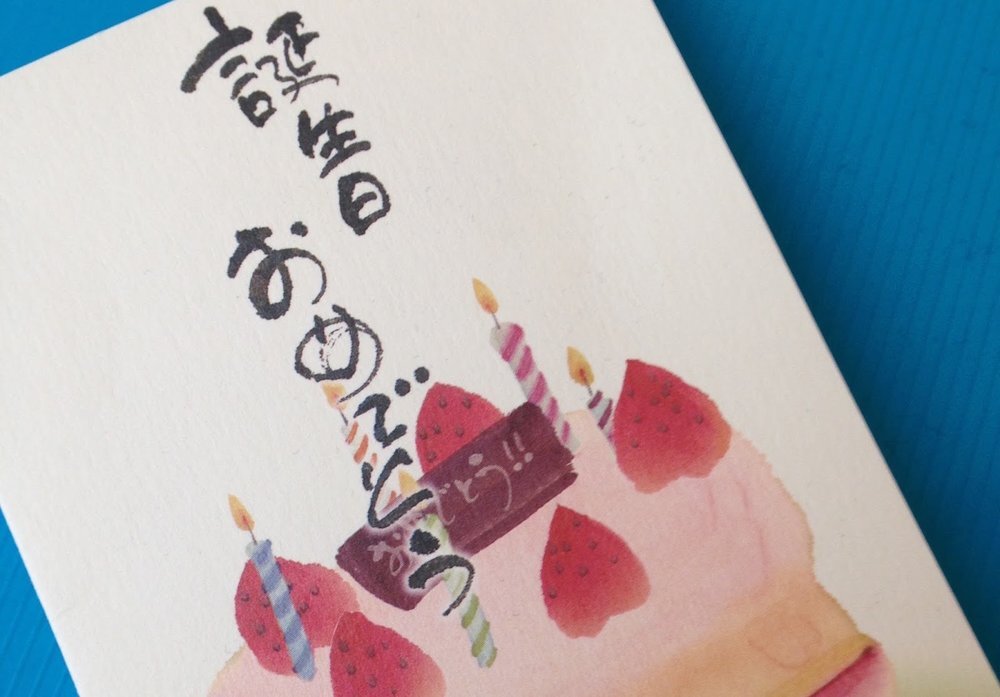

Six Ways To Say "Happy Birthday" In Japanese

So you want to wish your Japanese-speaking friends "happy birthday" in Japanese.

Whether you're sending a birthday card, or just writing a message, here are six different ways to share the love.

First of all, let's say “Happy Birthday”:

So you want to wish your Japanese-speaking friends "happy birthday" in Japanese.

Whether you're sending a birthday card, or just writing a message, here are six different ways to share the love.

First of all, let's say “Happy Birthday”:

1) お誕生日おめでとう! o-tanjoubi omedetou

Simple and classic, this one means "happy birthday", or literally "congratulations on your birthday".

2) お誕生日おめでとうございます。 o-tanjoubi omedetou gozaimasu

Stick a "gozaimasu" on the end to make it more polite.

Good for people older than you, people you know less well, and definitely good for your boss.

3) ハッピーバースデー!happii baasudee!

This one is actually one of my favourites - a Japan-ified version of the English phrase “happy birthday”.

Shop Japanese “Happy Birthday” T-shirts:

If you're writing a message, it's good to follow up after the birthday greeting by also wishing the person well:

1) 楽しんでください tanoshinde kudasai

"Have fun!"

e.g. お誕生日おめでとう!楽しんでください ^ ^

"Happy birthday! Have fun :)"

2) 素敵な一日を sutekina ichinichi o

"Have a great day."

e.g. お誕生日おめでとう!素敵な一日を〜

"Happy birthday! Have a great day."

3) 素晴らしい1年になりますように subarashii ichinen ni narimasu you ni

"I hope it's a wonderful year for you."

e.g. お誕生日おめでとうございます。素晴らしい1年になりますように。

"Happy birthday. I hope you have a wonderful year."

As you may have noticed, birthday messages wishing someone well for the year are kind of similar to a New Years' Greeting in Japanese.

それじゃ、素敵な一日を! sutekina ichinichi o!

And with that, I hope you have a wonderful day!

Learn beginner Japanese:

Get my newsletter:

Updated 10th August 2021

A Year of Monthly Japanese Learning Challenges

How do you keep practising Japanese, even when it doesn’t seem relevant? How do you stay motivated, when your life and your motivations change?

At the beginning of 2019, I decided to set myself a series of monthly Japanese study challenges. I’d do one every other month, and blog about it.

In January, I tried to speak Japanese every day for a month. This was probably the hardest challenge, from a logistical perspective. I don’t live in Japan, and we don’t speak Japanese at home (much). At the time, I was also working another job three days a week, where I wasn’t using Japanese at all. So speaking Japanese every day was, quite literally, a challenge.

How do you keep practising Japanese, even when it doesn’t seem relevant? How do you stay motivated, when your life and your motivations change?

At the beginning of 2019, I decided to set myself a series of monthly Japanese study challenges. I’d do one every other month, and blog about it.

In January, I tried to speak Japanese every day for a month. This was probably the hardest challenge, from a logistical perspective. I don’t live in Japan, and we don’t speak Japanese at home (much).

At the time, I was also working another job three days a week, where I wasn’t using Japanese at all. So speaking Japanese every day was, quite literally, a challenge.

But this was a great start to the year and probably one of my favourite things I’ve done using Japanese. Plus, I got to eat katsu curry at cafe an-an in Portslade and chalk it up as Japanese practice:

I Tried to Speak Japanese Every Day for a Month (Without Being in Japan)

In March, I tried shadowing every day.

What is shadowing? Most people are familiar with “listen and repeat” in language learning contexts. You listen to a conversation line-by-line and repeat each sentence after the recording.

Shadowing is different from simple “listen and repeat” in that you start speaking while the person on the audio is still talking. The goal is to be able to produce the dialogue with perfect pronunciation, as close to the recorded audio as possible.

I really enjoyed this challenge, and I also discovered that you can practise shadowing (quietly) in hotel rooms, waiting rooms, and even on the bus.

What is Shadowing and Can it Improve Your Spoken Japanese? I Tried Shadowing Every Day for a Month

In May, I read Japanese books every day. This was really fun, too, and not so hard once I got into a routine. If you get in the habit of taking a book with you everywhere you go, reading every day is relatively easy:

How to Read More in Japanese – I Tried Reading in Japanese Every Day for a Month

In July, I decided to play Japanese video games every day for a month, because who says challenges have to be challenging?

I played Japanese video games for about 20 minutes a day for a month, and here’s what I learned: six reasons to play video games in a foreign language.

This is not a “how to” post. I’m not going to tell you how to “learn Japanese in a week just by playing video games” or to claim this is a “quick route to fluency” (it’s not, namely because there is no quick route to fluency, just an endless and potentially very enjoyable road trip).

Instead, I’m just going to share some reflections on the very fun experience that was playing Japanese video games every day.

How to Practise Japanese by Playing Video Games Every Day

(IMAGE SOURCE: NINTENDO)

In September, I tried to watch Japanese TV every day. This is where the monthly challenges really started to come unstuck. September was a busy month, and life got in the way.

I also discovered that when a challenge isn’t very challenging, I don’t personally find it very motivating!

One fantastic thing that came out of this experience, however, was the idea for my new course Learn Japanese with Netflix! … but then covid-19 happened, which meant the Netflix course only ran for a few weeks. I hope to run it, or a similar course, again in the future.

Watching Japanese TV Every Day for a Month (Or, What to Do When Things Don't Go To Plan)

After that I took a two month break, and then in December, I got well and truly back on the horse, and spent a month practising handwriting kanji from memory every day.

I really enjoyed the routine of practising kanji again. I find kanji practice surprisingly relaxing - and I mentioned this to some students, who also said they find kanji writing practice relaxing, even meditative. Little and often is probably key.

"How Did You Learn Kanji?"

What next?

The process of setting bi-monthly goals was a stimulating and enjoyable experience, and I might repeat it another year, but I’m not doing monthly challenges in 2020.

We’re a few months into 2020, and due to covid-19, this year is already shaping up to be significantly more challenging than 2019.

2020 has already proved to be a year of radical change, for students at Step Up Japanese as well as for people all over the world. In March 2020 I moved all lessons online - another new challenge, but an enjoyable one.

I hope you stay healthy and safe throughout 2020, and that if Japanese study is a part of your life at the moment, that you enjoy it and have fun. And if life gets in the way sometimes….that’s okay too.

I Tried to Speak Japanese Every Day for a Month (Without Being in Japan)

Many people believe you need to live abroad to get speaking practice in a foreign language, but this isn’t true.

Similarly, people often assume that if you in Japan, like I did, you’ll pick up the language easily. But that’s not necessarily true either.

If you speak English, it’s possible - indeed easy - to live in another country for years and not become fluent in the language.

I didn't make any year-long New Years’ Resolutions this year. Instead, I decided to set myself some monthly language-related challenges. I’ll decide them as the year goes on, and I’ll probably do one every other month.

In January, I decided to speak Japanese every day for a month.

Many people believe you need to live abroad to get speaking practice in a foreign language, but this isn’t true.

Similarly, people often assume that if you live in Japan, like I did, you’ll pick up the language easily. But that’s not necessarily true either.

If you speak English, it’s possible - indeed easy - to live in another country for years and not become fluent in the language.

I didn't make any year-long New Years’ Resolutions this year. Instead, I decided to set myself some monthly language-related challenges. I’ll decide them as the year goes on, and I’ll probably do one every other month.

In January, I decided to speak Japanese every day for a month.

For context: I live in the UK, I don’t speak Japanese at home, and although I work as a Japanese teacher, I don’t currently teach Japanese every day. So this was going to take some effort.

When I lived in Japan, I was using Japanese every day. My Japanese reading and writing is significantly better now than it was then (I have five years’ more practice under my belt). But I don’t speak Japanese every day like I used to. So I decided to try!

I set myself the following, slightly arbitrary, rules:

1) Speak in Japanese for a minimum of 15 minutes a day (ideally more)

2) Texting doesn't count

3) Talking to yourself doesn't count either*

*Incidentally, I am a big fan of talking to yourself as a method of practicing a language. But I decided it wouldn’t count for this challenge.

Day 1

Every year on January 1st the Brighton Japan Club has a New Year’s swim in the sea. A great opportunity to practice different words for “ohmygodit’sfreezing” .

I don't swim this year, just go along afterwards for a post-swim lunch and some Japanese- and English-language chat in a café.

Tip number 1: Find people to speak with. You can’t practice speaking by yourself. Could you join a group class or a social club?

Photo from last year’s New Year’s Day Swim (2018). Photo by Tom Orsman

Day 2

I get up an hour early and have a 30 minute italki lesson on Skype before work. Italki is a website and app where you can find online language teachers.

I plan to start teaching on Skype in 2019, possibly using italki, so I take the opportunity to ask the teacher all about italki and how she finds it. The teacher is friendly and I have fun talking with her. I’ve never met her before – I just found her on italki.

Day 3

I go to the weekly Japanese-English Language Exchange with Brighton Japan Club. It’s a good way to meet Japanese people, and people interested in Japan. There’s usually a good mix of old and new faces, which keeps things fresh.

Day 4

I have dinner with a Japanese friend I met last month at the end-of-year party of the Brighton & Hove Japanese Club (a similarly named but different group to the Brighton Japan Club). We go to Goemon, arguably Brighton’s best ramen bar. We talk in Japanese all night.

Day 5

I go to 書き初め kakizome (first calligraphy of the year) at Brighton Japan Club. I don't speak much Japanese at this event and on the way home I wonder if it ‘counts’… I have a lot of fun though.

Day 6

I Skype with a friend in Japan, who I met when I lived in Nagoya. This was probably the most fun thing I did all week. I saw her last spring, so catching up over video chat, there is a lot to talk about.

I reflect that being able to talk with friends in Japanese is really important to me.

Tip number 2: make friends who speak the language you’re learning

Day 7

I have a 30 min italki “instant lesson” with teacher S. She used to live in Canada where she ran language exchange events. She’s thinking about studying abroad in the UK, so we chat about that. She talks quickly, and so do I, happily and unthinkingly.

Day 8

I go to Café an-an in Portslade for lunch. I chat briefly with the owner, Noriko, while eating katsu curry. I take home some 花びら餅 hanabira mochi (“flower-petal mochi”) sweets.

After lunch I have a video meeting scheduled with Jess from Nihongo Connection. We chat in Japanese for the first half of the call - Jess is British, so I wasn't expecting to talk with her in Japanese, but its fun. We make plans to meet up the following month in Edinburgh.

Day 9

Skype lesson with Sugita-sensei. I met Sugita-sensei at Yamasa in Okazaki, where I studied on the Advanced Japanese Studies Program in 2014. Now, I consider myself lucky to call him a friend as well as 先輩 (senpai; senior colleague) and teacher. When I have time, I usually have a Skype lesson with him once a week. We read fiction and news articles, and sometimes I write stories or essays and we work together to correct them.

Day 10

I’m going to London for the day, to the video-games exhibition at the V&A and to see Macbeth. I have an italki lesson with teacher H in the morning. I ask her how I can improve my speaking. She says the goal “improve my speaking” is too broad, and I agree. She suggests I should think about what kind of speaking I want to get better at; and what I want to be able to talk about. Then, focus in on those topics, by reading about them. This seems like very good advice.

Tip number 3: find a good teacher

Day 11

I go out for dinner with a Japanese friend and a Spanish friend. We switch between speaking English and Japanese all night.

Day 12

I spend the day out with my boyfriend and some friends. My boyfriend can speak Japanese, but we don’t speak Japanese together, because - well, just because we don’t.

We get home at 11:45pm and I realise I haven’t spoken any Japanese yet today. Reluctantly, my boyfriend agrees to speak Japanese with me until midnight. We set a timer for 15 minutes and I pour him a beer.

Day 13

I go to Brighton Japan Club’s annual new-year mochi-making event. My favourite events are the ones involving food! I eat squishy rice cakes and chat with some new people.

Day 14

I have an italki lesson at 7am with a new teacher, T. This is the only italki lesson I had that wasn’t really for me. He suggests some resources that are way too low a level for me and a Japanese grammar website with picture explanations that I think are kind of unclear.

I take this as a useful lesson in how not to teach on Skype.

Day 15

Term starts today, which means I teach STEP 1 (beginner) and STEP 2 (upper beginner) Japanese classes on Tuesday nights. STEP 1 students are doing a quiz about which country well-known brands are from. STEP 2 students practice asking each other to do things, which is always fun.

On the way home I wonder if teaching beginner level classes counts as speaking practice for me. Probably not, but I decide to let it count for this experiment anyway. It’s still three hours of Japanese time.

Day 16

7am Skype class with Sugita-san. We read a section on “Friendship” from Tsurezuregusa (徒然草, Essays in Idleness), a collection of essays written by the Japanese monk Yoshida Kenkō in the 14th century, and talk about it.

Day 17

I teach two more Japanese classes, STEP 3 and STEP 4, at pre-intermediate and intermediate level.

My higher-level classes usually need a bit less structure than beginner classes. I still speak more slowly than natural speech, but I don't plan the wording of my instructions in the same way as I do with beginner classes. Especially in STEP 4, students like to chat and always have good questions, which they can ask in Japanese.

Tip number 4: ask questions!

Day 18

I’m going to my office job 9-5 today (no chance to speak Japanese there), and to a birthday party afterwards (no Japanese speakers). So I get up at 7am and have another italki lesson with M-sensei. We talk about Brexit…

Day 19

I go to a Heart Sutra writing workshop with the Brighton Japan Club. The workshop is in Japanese with English interpretation. I have fun listening along to both.

Day 20

I Skype with another Japanese friend in Japan. She had a baby recently, so a lot has changed for her. She fills me on her new life. After our conversation, I walk around all day with a huge smile on my face.

Day 21

Another italki lesson with M-sensei. She is an ex TV announcer, so I ask a bunch of questions about pitch accent. (Briefly: Japanese has high-low tones, and pronouncing a word with the wrong pitch accent pattern makes you sound unnatural).

She says that my pitch is mostly good but I make occasional pitch and stress mistakes which identify me as a non-native speaker.

Like many non-native speakers, I have never explicitly learned Japanese pitch accent, and I think this is probably something I should rectify. She has me read an article from NHK news, and corrects my pitch accent. It’s hard.

I also go to see a Japanese film with another of my students – 君の名は (kimi no na wa; ‘Your Name’). We see another former student of mine in the foyer and speak briefly in Japanese.

Day 22

I teach two beginner classes. STEP 1 students are practicing verbs like 行きます、来ます、帰ります (ikimasu, kimasu, kaerimasu; go / come / come back), so I have them read a short story about my trip to Disneyland last year.

I am reminded that reading helps with speaking. We need to be exposed to lots of language in order to eventually produce it.

STEP 2 students are learning about giving directions. Confession: I find teaching directions really hard. I used to practice this by playing video games (students shout out directions while one person is playing), but the flash game wont work on the classroom computer any more. I consider switching this up next year.

I think more about input/output. How useful is it for my students to learn to give directions in Japanese? Not very. How useful is it for them to understand verbal directions in Japanese? If they go to Japan, probably very useful.

Tip number 5: Read! There can be no meaningful output without input.

Day 23

I ask Sugita-san more about pitch accent. He is currently teaching on a course for people studying to become Japanese teachers in Okazaki, Japan. He says many Japanese people don’t explicitly understand pitch accent either.

My boyfriend shows me a video series on Japanese phonetics by Dogen, the Japanese teacher and YouTuber. I go on an internet deep dive into pitch accent. Maybe that will be my next challenge…?

Day 24

I teach two Japanese lessons. In STEP 3 (lower-intermediate) we cover short forms in casual speech. I love teaching this because it’s so ridiculously useful and common in everyday speech. It’s not in the textbook we use at all, so I made my own materials.

Day 25

I go to the pub again with my Spanish friend and Japanese friend. Japanese friend is going back to Japan the following day. He has also, excitingly, just become a father. Lots to talk about. As before, we probably talk about half in English and half in Japanese.

Day 26

I go to an 生け花 ikebana (flower arranging) workshop with the Brighton Japan Club. The workshop is in English, but I chat with the organisers in Japanese a bit.

I have to rush off as I am going to see the film 万引き家族 (Manbiki Kazoku; Shoplifters) with my student in Eastbourne. I love hanging out wth my adult students outside of class, and I’m always super pleased when they invite me to spend time with them, especially when it’s Japan-related!

Tip number 6: find fun things to do related to the language you’re learning

Day 27

I go to Kantenya, the Japanese supermarket, and buy sashimi-grade tuna to make まぐろたたき丼 (maguro tataki don; chopped tuna rice bowl). I ask the staff how long it will take to defrost the tuna. She explains you can just take it out the freezer, or there is a proper technique that’s should make it taste better. She produces a handout that shows how to do it! They have the handout in Japanese and in English. I take the Japanese one. We talk about the Manbiki Kazoku film too.

Day 28

I have a 30 minute italki lesson with N-sensei. We talk about her plans to study abroad in the UK and my time in Japan. It’s fun, but I don’t really learn anything.

I reflect that just talking is not very good practice for me personally. I think I need to talk about difficult topics and be corrected quite closely.

Italki makes a distinction between “community tutors” (unqualified) and “professional teachers”. N-sensei is a community tutor, and mostly does “free talk”. On reflection, this is not really what I need from a paid class.

Day 29

Before my group classes, I teach a private lesson in a cafe. We go over some grammar points my student has questions about, but mostly I just try and get her to speak Japanese, without using English.

Most students need more speaking practice. The experience of being totally lost in language, and not understanding most of what’s going on is something we may not have felt since childhood. As such, it can be really scary.

I believe it’s a feeling you need to get used to if you’re going to make progress. I tell my student I want her to be a little bit outside her comfort zone - not so far that it’s terrifying, but just enough that she’s pushing herself and learning new things.

Day 30

Skype lesson with Sugita-san. We read ネギを刻む (negi o kizamu; literally “Chopping Leeks”) a short story by 江國香織 (Kaori Ekuni). One of my favourite things about my lessons with Sugita-sensei is that he introduces me to stories and essays I wouldn’t necessarily find by myself.

Day 31

A Japanese volunteer, Aria, comes to class with me. My students ask her questions and talk with her in Japanese. We also make 四コマ漫画 (yon-koma manga), manga comic strips with four panels. Aria helps out a lot and my students enjoy speaking with her.

I get requests from local Japanese people to come and volunteer at class fairly frequently. I’m grateful for their help, and it’s good for my students to practice speaking in this way.

Speaking in Japanese every day for a month - my conclusions

1) Find a good teacher

You need a teacher who fits your needs. If you just want speaking practice, find someone who will “just talk” with you. If you want to be corrected, ask your teacher to correct you more. Chatting with friends is good, but your friends aren’t language teachers (probably)

2) Make friends

The absolute best things I did this month – not just in this challenge, but the most fun things I did this month overall – was talk with my friends in Japan.

I was reminded too that being able to talk with friends in Japanese is really important to me.

3) Connect offline as well as online

If you live in a country where Japanese isn’t widely spoken, you might need to go online to find people to talk with. But I did get a bit bored of having so many Skype lessons, especially as I started to feel I wasn’t getting much out of it.

Plus, italki is kind of expensive to take lessons so often. I plan to start teaching online late this year, so I told myself that taking Skype lessons was research…

Speaking to people offline was way more fun for me.

4) Be open to surprises!

Japanese popped up in some unexpected places this month. I knew that Jess runs a Japanese speaking club, but she’s English so I wasn't expecting us to talk in Japanese so much. That was a lot of fun.

5) Find work using your languages

I get to use Japanese in my work, because I teach Japanese. Arguably it’s not really speaking practice for me, but my students always ask me good questions and help me see things about the Japanese language from a new perspective.

If you want to get serious about having more chance to use your Japanese, consider looking for a job or a voluntary position where you can use it. Could you work in a Japanese restaurant, or for a Japanese travel agency?

And finally…

At an advanced level, speaking a lot is actually not a great way to get better at speaking.

One of the italki teachers told me: “You don't need speaking practice, because you can already speak. If you read more, you’l be become able to talk more fluently about complex topics.”

This fits with what I know about input-based methods of learning languages – essentially, that these two things happen in this order:

1. You get input — you read and listen to sentences in some language. If you understand these sentences, they are stored in your brain. More specifically, they are stored in the part of your brain responsible for language.

2. When you want to say or write something in that language (when you want to produce output), your brain can look for a sentence that you have heard or read before — a sentence that matches the meaning you want to express. Then, it imitates the sentence (produces the same sentence or a similar one) and you say your “own” sentence in the language. This process is unconscious: the brain does it automatically.

(quote from Antimoon)

There can be no good quality output (speaking the language; writing it well) without massive amounts of input (listening to and reading the language).

But if you’re a beginner or intermediate learner, you’re probably not getting enough speaking practice.

Speaking Japanese every day was really fun. As you can see, it didn’t quite have the result I was hoping for, but I definitely learned a lot. Why not give it a go?

Hiking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage Trail in 2018 - A Round-Up

The week I spent last spring walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail was peaceful, thought-provoking, and challenging - often all at once.

Here’s all my writing about that trip in one place.

The week I spent last spring walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail was peaceful, thought-provoking, and challenging - often all at once.

Here’s all my writing about that trip in one place.

Part 1 - Plan, plan, plan!

Are you a planner? Or a no-planner?

Some people like to "wing it" when they travel. They book a ticket and turn up, deciding what to do once they arrive. Me, I like to have things planned out. Especially when the trip involves a week of solo walking in Japan…

Click here to read Part 1 - Plan, plan, plan!

Part 2 - The Best First Day in Japan

Spoiler alert: this post isn't about the Shikoku pilgrimage, although it is about the same trip. It's about what I did with my spare first day in Nagoya: the lost day...

Arriving first thing in the morning on a long-haul flight is not ideal. You're tired, jet-lagged and yet you need to stay awake until a normal bedtime, so you can adjust your body clock.

I had almost 12 hours to kill on that first day, and was waiting for my friends to finish work.

So what do you do with a whole day to yourself?

Ciick here to read Part 2 - The Best First Day in Japan

Part 3 - What To Wear

When I told my Japanese friends I was planning to walk the Shikoku Henro trail, several of them said the same thing. "Are you going to wear a hat?"

For many people, the image of a walker in a bamboo hat is the first thing that comes to mind when they think of the pilgrimage.

But what "should" you wear on the Shikoku 88, a Buddhist pilgrimage trail?

Click here to read Part 3 - What To Wear

Part 4 - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

A stranger, they say, is just a friend you haven't met yet.

And talking to strangers is a great way to speak lots of Japanese. I did lots of this while walking the first section of the Shikoku pilgrimage this spring.

But how do you start a conversation with a stranger? Here are some ideas to get you going, even if you're a beginner at Japanese.

Click here to read Part 4 - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

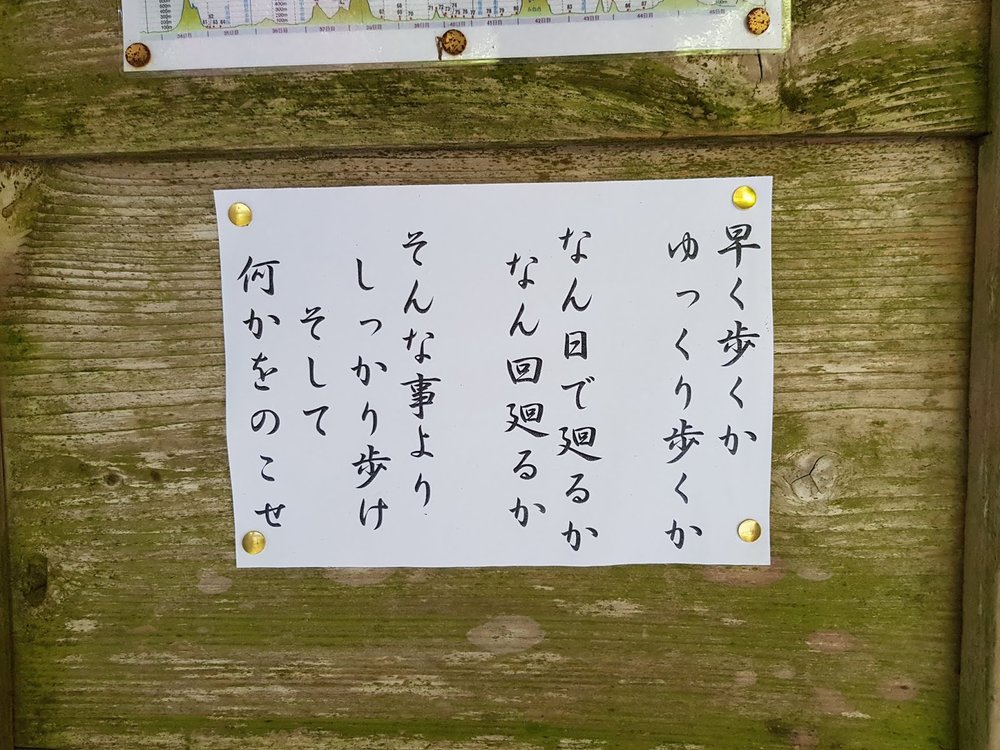

Part 5 - Signs of Shikoku

I heard lots of "gambatte kudasai" (“keep going!”) walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage this spring. It was written everywhere too - in fact there were lots of interesting signs.

The pilgrimage trail is pretty well marked. Signage is consistently spaced, and in many places there's a way-marker every 100 metres.

But it's also endearingly inconsistent in design - on some stretches every sign is different, and many are handmade….

Click here to read Part 5 - Signs of Shikoku

Part 6 - Shouting at the French

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!" I shouted. ("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move.

They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!" ("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly. I waved the little grey bag with its digital camera inside. "KAMERA!"

I still couldn't make out their faces, but I thought I saw a glimmer of recognition. One of the pair walked towards me, and it was only then that I saw her face.

"I thought you were Japanese," she said, and I heard a European accent I couldn't place.

"I thought you were Japanese," I said…

Click here to read Part 6 - Shouting at the French

Part 7 - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

Kyūkei shimashou" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called kyūkeijo 休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to

strike up a conversation.

Click here to read Part 7 - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

Part 8 - O-settai, or, "I'll treasure this tissue case"

Near Kumadani-ji, temple number 8, we had stopped in front of some glorious cherry blossom, and I got chatting to two older gentlemen who were walking the trail. One told me he had never spoken to a gaijin-san, foreigner, before. We took some pictures in front of the cherry blossom, and walked up the hill together.

Further up the road, a lady came out of her house and gave us some hard-boiled sweets.

The sweets were a form of o-settai, small gifts given to walking pilgrims. Traditionally, pilgrims didn't carry money, so they were helped along their way by gifts of food, lodging and other acts of generosity from local people.

“Wait here,” she said when she saw me, “I have something else for you.”

Click here to read Part 8 - O-settai, or, "I'll treasure this tissue case"

Part 9 - Eating Shōjin Ryōri - Buddhist temple food

The “strange” meals were “quite unlike any food I’ve ever tasted”, wrote one visitor to the Sekishoin Shukubo temple in Mount Kōya, eliciting the blunt reply from one monk:

“Yeah, it’s Japanese monastic cuisine you uneducated fuck.”

Guests online also complained about the lack of heating in the Buddhist temple, the absence of English tour guides, and “basic and vegetarian” food.

I stayed in a couple of shukubo (宿坊) earlier this year…

Click here to read Part 9 - Eating Shōjin Ryōri - Buddhist temple food

Thanks so much for reading! I hope you found it useful and/or interesting.

I can’t wait to go back and walk the next bit…

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

"Kyūkei shimashou" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called kyūkeijo 休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to strike up a conversation …

"

Ky

ū

kei shimashou

" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called

kyūkeijo

休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to

.

Luckily for me, the bit of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail I walked this spring had interesting and varied rest stops throughout. So what kind of places are used as

kyūkeijo

?

1) Temple outbuildings

On the first day I walked with another pilgrim, who I'd met at temple number 1. We stopped around midday, at a

ky

ū

keijo

in a temple outhouse building.

The women inside offered us tea and sweets, and in exchange we handed them

osamefuda

(納め札),

slips of paper with your name and a message, on which pilgrims carry instead of money

.

(...traditionally, I mean. Most modern pilgrims carry money too now.)

I was grateful to receive the tea and sweets, but even more grateful to have the opportunity to chat with these friendly women, who said they had lived in Shikoku all their lives.

They told me their ages (in their 70s and 80s), and that some of them had walked the 750-mile pilgrimage three or four times in their lifetimes.

2) Private houses

Some rest stops are out the front of a private home. The owners prepare tea or hot water each morning, and leave it out for visiting walkers:

I sat at this one alone and ate my packed lunch. It was a baking hot day, so I was glad to be out of the sunshine.

Both these

ky

ū

keijo

had signs explaining that the snacks and drinks are offered for free as

o-settai

(お接待), small gifts given to walking pilgrims to help them on their way.

3) Vending-machine seating

Usually, at the temple itself there will be a vending machine or two, with seating next to it.

It can be seen as impolite to eat or drink while walking in Japan, so vending machines often have seats next to them.

You can enjoy your snack first, and then walk around afterwards. Remember, rest is important!

I sat at this one and had a can of iced coffee:

I also spotted this set of hardwood chairs in one temple rest area, which look like they're set up to accommodate a whole coach trip:

4) Outdoor rest stops

In the mountains, a clearing with a place to sit down can be a really nice surprise. This one below had obviously taken some work to create, being in the middle of the forest. And it was labeled (in English!) as a "lounge", which I thought was just great.

It clearly is a lounge. It just happen to be outside!

5) Wooden huts

There are also small rest houses maintained by community groups. These are good for getting out of the sun (or the rain!)

This one had a formidable list of rules about not leaving rubbish behind, and stating that it was only for the use of walking pilgrims. It was on a main road in a town, so I guess they'd had problems before.

Anyway, it seems the rules are being followed these days, as the house was spotless:

I had some tea and a delicious fresh orange, read the extensive rules, and wrote in the guestbook.

Towards the end of my walk, I spotted another outdoor rest stop. This one was also purpose-built, with concrete table and seating, and a great view.

What I liked was that people had added extra seating - the sofa and chair, presumably from someone's home:

But the best type of rest stop is when you get to your lodging for the night, and can put your feet up.

それでは、休憩しましょう!

Sore dewa, kyūkei shimashou!

So,

let's take a break!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move. They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly …

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move.

They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly. I waved the little grey bag with its digital camera inside. "

KAMERA

!"

I still couldn't make out their faces, but I thought I saw a glimmer of recognition. One of the pair walked towards me, and it was only then that I saw her face.

"I thought you were Japanese," she said, and I heard a European accent I couldn't place.

"I thought

you

were Japanese," I said.

"We're French," she offered.

"Ah." I paused. "Um, bonjour?"

We walked together a little bit, and then I left them at a rest stop.

I bumped into them again later in the week, at breakfast in the inn we were staying at. The women was showing the owner a piece of paper, and he was squinting at it.

They seemed to be having some difficulty, so I offered to help.

I squinted at the piece of paper too, and was suddenly transported back to year 6, learning about French cursive in class.

There was the name of a youth hostel in the next town over, and a short message underneath. It was all in romaji (Japanese written in the roman alphabet), but in looping, cursive letters:

futari desu. kyou, yoyaku onegai shimasu.

"For two people. A reservation for tonight, please."

I read it aloud to the owner, who promptly got on the phone and made a reservation for them.

"Your note was fine," I told them. "I think he just didn't have his glasses."

Or perhaps he couldn't read their cursive? I didn't say that though.

I wondered later how the rest of their trip went. They seemed to be having a great time.

There's no right or wrong way to walk the Shikoku pilgrimage. And it's possible to travel in Japan without any Japanese language at all. But if you can learn even a bit of the language, you'll have a richer experience, I think.

And you'll understand when someone's trying to tell you you've dropped your camera.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

"Gambatte kudasai" is sort of untranslatable but also extremely translatable. (The best kind of Japanese phrase!)

Gambatte kudasai means "do your best!" or "go for it!"

When I started learning Japanese at university in 2008, my classmates and I thought the phrase gambatte kudasai was quite funny for some reason ...

"Gambatte kudasai"

is sort of untranslatable but also extremely translatable. (The best kind of Japanese phrase!)

Gambatte kudasai

means

"do your best!"

or

"go for it!"

When I started learning Japanese at university in 2008, my classmates and I thought the phrase

gambatte kudasai

was quite funny for some reason. So when we had to write a short dialogue about a holiday and commit it to memory as part of a speaking test, my partner and I shoehorned in a bunch of "

gambatte kudasai"s.

My partner showed our work to his (Japanese) mum, who sent it back covered in red corrections and with all our "

gambatte kudasai

"s crossed out. Apparently they didn't work in context.

The problem is, I knew that

gambatte kudasai

means "try your best", but I didn't know it sounds weird if you're talking about buying a plane ticket...

I heard lots of "

gambatte kudasai"

walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage this spring. It was written everywhere too - in fact there were lots of interesting signs.

The pilgrimage trail is pretty well marked. Signage is consistently spaced, and in many places there's a way-marker every 100 metres.

But it's also endearingly inconsistent in design - on some stretches every sign is different, and many are handmade.

There are these little

aruki-henro

(歩き遍路

;

walking pilgrims) to mark the way:

Red is the dominant colour - sometimes just a red arrow, like this stone below. Actually, there's kanji (Chinese characters) carved into the stone too, but it's difficult to see:

Some signs are in English as well as Japanese, although this was less common:

Some show you which way to turn at an upcoming junction. This took a bit of getting used to, but was very useful. Even in rural areas, I didn't get lost once.

Sometimes, the signs just said 道しるべ (

michi-shirube;

guidepost).

Note that many of these handwritten signs are in vertical text, and from right to left:

This next sign packs a lot of meaning into a few kanji characters:

空海

kūkai

(aka Kōbō Daishi, the Buddhist monk in whose footsteps pilgrims walk)

遍路道

henro michi

(pilgrimage trail)

同行二人

dougyou ni-nin

("two people going together" - the idea that the walking pilgrim is never alone, as Kōbō Daishi is walking with you)

The tough parts of the trail are called

henro korogashi

(遍路ころがし; "the place where the pilgrim falls down").

This bit of

henro korogashi

had even more signposts throughout, so you know how far you have left to go. There's a 1/6 sign to let you know when you are one-sixth of the way through; then 2/6 for two-sixths, and so on.

This picture was taken just before the last stretch, when I was a bit tired:

And of course there are plenty of little signs saying がんばって下さい

gambatte kudasai

(

"keep going!"

.

This made me smile, and was genuinely quite encouraging.

We all need a bit of encouragement sometimes!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

P.S.

If you can't read Japanese, but you want to recognise common signs and notices before your holiday to Japan, you should check out my new

Survival Japanese for Beginners

-

, it starts Thursday 26th July in central Brighton.

Or if you do read Japanese but want to get better, join us for

- a summer course in learning Japanese by reading lots of easy books.

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.