Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Why Does The Japanese Language Have So Many Alphabets?

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

Until the 1st or 2nd century, Japan had no writing system. Then, sometime before 500AD, kanji - Chinese characters - made its way to Japan from China (probably via Korea).

These characters were originally used for their meaning only - they weren't used to write native Japanese words.

↓ And at that time, Japanese writing looked like this. Look, it looks like Chinese!

(Image Source - Nihon Shoki, Wikipedia)

But it was inconvenient not being able to write native Japanese words down, and so people began to use kanji to represent the phonetic sounds of Japanese words, not only the meaning. This is called manyougana and is the oldest native Japanese writing system.

For example, in manyougana the word asa (morning) was written 安佐 (that's a kanji for the “a” sound - 安 - and another for the “sa” sound - 佐). These characters indicate the sound of the word - “asa” - but not its meaning.

In modern Japanese we'd use 朝, the kanji that means "morning" for asa. This character shows its meaning AND its sound.

The problem was, manyougana used multiple kanji for each phonetic sound - over 900 characters for the 90 phonetic sounds in Japanese - so it was inefficient and time-consuming.

Gradually, people began to simplify kanji characters into simpler characters - that's where hiragana and katakana came from.

Katakana means "broken kana" or "fragmented characters". It was developed by monks in the 9th century who were annotating Chinese texts so that Japanese people could read them. So katakana was really an early form of shorthand.

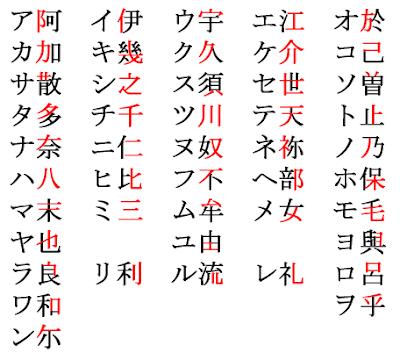

Each katakana character comes from part of a kanji: for example, the top half of the kanji 呂 became katakana ロ (ro), and the left side of the kanji 加 became katakana カ (ka).

↓ Each katakana comes from part of a kanji.

(Source - Katakana origins, Wikipedia)

Women in Japan, on the other hand, wrote in cursive script, which was gradually simplified into hiragana. That's why hiragana looks all loopy and squiggly. Like katakana, hiragana characters don't have meaning - they just indicate sound.

↓ How kanji (top) evolved into manyougana (middle in red), and then hiragana (bottom).

(Source - Hiragana evolution, Wikipedia)

Because it was simpler than kanji, hiragana was accessible for women who didn't have the same education level as men. The 11th-century classic The Tale of Genji was written almost entirely in hiragana, because it was written by a female author for a female audience.

Modern Japanese writing uses all three of these “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji - often all mixed up in the same sentence.

What would 12th-century people in Japan think of my students, 900 years later, learning hiragana as they take their first steps into the Japanese language?

First published 28th Oct 2016

Updated 27th Jan 2020

What’s the difference between sensei and kyōshi?

The word "sensei" is pretty well-known even among people who don't speak Japanese, but did you know that you shouldn't use sensei about yourself?

Here's what the textbook has to say:

"Use 'kyōshi' for yourself and the respectful 'sensei' for another person."

That's a pretty good starting point. But there's a bit more to it than that.

Japanese has (at least) two words for "teacher".

The word "sensei" is pretty well-known even among people who don't speak Japanese, but did you know that you shouldn't use sensei about yourself?

Here's what the textbook has to say:

"Use 'kyōshi' for yourself and the respectful 'sensei' for another person."

That's a pretty good starting point. But there's a bit more to it than that.

1. Kyōshi = school teacher

Kyōshi means the academic kind of teacher, someone who teaches in a school:

(私は)高校の教師です。

(watashi wa) kōkō no kyōshi desu.

I'm a high school teacher.

Images: Irasutoya

2. Sensei is a title

Sensei, however, is a respectful title, and should be used when talking about other people:

彼は中学校の先生です。

kare wa chūgakkō no sensei desu.

He's a junior high school teacher.

Watashi wa sensei desu is best avoided.

3. Sensei = master

Sensei can also be used more generally for a person who teaches something.

People who teach flower arranging or martial arts, for example, are sensei:

お花の先生

ohana no sensei

flower-arranging teacher

空手の先生

karate no sensei

karate teacher

茶道の先生

sadō no sensei

teacher of tea ceremony

If you're talking about yourself, however, you still shouldn't go around calling yourself sensei.

You can use the verb 教える oshieru (to teach) instead:

(私は)お花を教えてます。

(watashi wa) ohana wo oshiete imasu.

I teach flower arranging.

Certain types of professionals such as doctors or lawyers are also sensei (but again, not kyōshi).

4. "Sensei!"

Sensei is attached after teachers' names instead of san:

山本先生

Yamamoto Sensei

= Mr/Ms Yamamoto; “Yamamoto teacher”

It's pretty common to drop the name, too, and just call your teacher sensei:

先生、おはようございます!

Sensei, ohayō gozaimasu!

“Good morning, teacher”

So to summarise:

Use '“kyōshi” for yourself and the respectful “sensei” for another person.

“Sensei“ is not just for teachers, but also for masters of other skills, and for doctors

Affix “sensei” to your teacher’s name to show respect

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.