Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Plateaus in Language Learning and How to Overcome Them

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth. I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth.

I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

I told this nice, patient lady that I was studying Japanese and she asked me how long I was staying in China for. I wanted to tell her I was going back to England next Thursday, but instead I said 先週の水曜日に帰ります (senshuu no suiyoubi ni kaerimasu) - "I'll go back last Wednesday."

OOPS.

I think about this day quite a lot because it shows, I think, that although I'd studied lots of Japanese at that point my communicative skills were pretty poor. I considered myself an intermediate learner, but I couldn't quickly recall the word for Wednesday, or the word for last week.

I realised at that point that I hadn't made much real progress in the last two years. The first year I zipped along, memorising kana and walking around my house pointing at things saying "denki, tsukue, tansu" (lamp, desk, chest of drawers) But after that my Japanese had plateaued.

So, I started actively trying to speak - I took small group lessons, engaged in them properly, did the prep work. I wrote down five sentences every day about my day and had my teacher check them. I met up with a Japanese friend regularly and did language exchange - he corrected my grammar and told me when I sounded odd (thanks, Kenichi!)

(Most of this happened in Japan, but like I said, you don't need to live in Japan to learn Japanese.)

And I came out of the plateau. I set myself a concrete goal - to pass the JLPT N3. The JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) is a standardised test in Japanese, for non-native speakers. N3 is the middle level - intermediate.

Once I’d passed that, I started aiming for N2, the next level up. I had some job interviews in Japanese, a terrifying and fascinating experience.

I wanted to get a job with a Board of Education, and a recruiter told me you needed N1 - the highest level of the JLPT - for that, so I started cramming kanji and obscure words. I was back on the Japanese-learning train.

I didn't pass N1 though, not that time.

And I was bored of English teaching and didn't want to wait to pass the test before I got a job using Japanese - that felt a bit like procrastinating - so I quit my English teaching job and got a job translating wacky entertainment news.

And after six months translating oddball news I passed the test.

That's partly because exams involve a certain amount of luck and it depends what comes up. But I also believe it's because using language to actively do something - working with the language - is a much, much better way of advancing your skills than just "studying" it.

Thanks to translation work, I was out of the plateau again. Hurrah!

When you're in the middle of something - on the road somewhere - it's hard to see your own development.

Progress doesn't move gradually upwards in a straight line. It comes in fits and starts.

Success doesn't look like this:

It looks like this:

And if you feel like you're in a slump at the moment, there are two approaches.

One is to trust that - as long as you're working hard at it - if you keep plugging away, you'll suddenly notice you've jumped up a level without even realising. You're working hard? You got this.

The other approach is to change something. Make a concrete goal. Start something new. Find a new friend to talk to or a classmate to message in Japanese. Talk to the man who owns the noodle shop about Kansai dialect. Write five things you did each day in Japanese. Take the test. Apply for the job. がんばる (gambaru; “try your best”).

Originally posted February 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

Three Favourite Japanese Jokes

The worst job interview I ever had started with the interviewer asking me to tell him a joke.

I sat there flustered for a while before mumbling something about a man walking into a bar. The interviewer rolled his eyes.

I didn't get the job.

Sitting in a smokey cafe after the interview I remembered The Michael Jackson Joke which is probably the best beginner-Japanese joke of all time. I should've told him that one! Although he probably would have rolled his eyes at that too...

The worst job interview I ever had started with the interviewer asking me to tell him a joke.

I sat there flustered for a while before mumbling something about a man walking into a bar. The interviewer rolled his eyes.

I didn't get the job.

Sitting in a smokey cafe after the interview I remembered The Michael Jackson Joke which is probably the best beginner-Japanese joke of all time. I should've told him that one! Although he probably would have rolled his eyes at that too...

They say explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog - you understand it better but the frog dies in the process. So with that in mind, here are my three favourite, brilliant, terrible Japanese jokes.

The Michael Jackson Joke

「マイケルジャクソンの好きな色は何ですか。」

「青」

Maikeru Jakkuson no sukina iro wa nan desu ka.

Ao!

"What's Michael Jackson's favourite colour?"

"Blue."

You have to really commit to the punchline for this one. You can even tell the question in English and the punchline in Japanese, as long as the person you're speaking to knows the Japanese word ao.

I once told The Michael Jackson Joke to a friend while standing at a traffic light in Nagoya and a stranger in front of us burst out laughing. True story.

↓ (Skip to 1:05)

2. The Hawaiian Dentist Joke

「どうしてハワイ人は歯医者に行かないの? 」

「歯はいいから!」

Doushite Hawaii jin wa haisha ni ikanai no?

Ha wa ii kara.

"Why don't Hawaiians go to the dentist?"

"Because their teeth (=ha) are good (=ii)"

My friend Kendal sent me this one last week. ありがとうケンダル!

3. The Panda Joke

パンダの好きな餌は?

パンだ。

Panda no sukina esa wa?

Pan da.

"What's a panda's favourite food?"

"Bread (=pan)"

Pandas and puns are probably two of my favourite things. This joke has both.

What's your favourite Japanese joke? Have you ever told a joke in a job interview? Let me know in the comments!

First published 10 Feb 2017

Updated 31 March 2020

"How Did You Learn Japanese?"

When I tell people I'm a Japanese teacher they quite often ask: how did you learn Japanese? And I don't find this question particularly easy to answer.

Sometimes I give a quick answer which is that I used to live there.

But you can live in Japan for years and not learn Japanese.

I've met lots of people like this (and there's nothing wrong with that, unless learning Japanese is the reason you moved to Japan).

The long and more honest answer to "how come you speak Japanese?":

When I tell people I'm a Japanese teacher they quite often ask: how did you learn Japanese? And I don't find this question particularly easy to answer.

Sometimes I give a quick answer which is that I used to live there.

But you can live in Japan for years and not learn Japanese.

I've met lots of people like this (and there's nothing wrong with that, unless learning Japanese is the reason you moved to Japan).

The long and more honest answer to "how come you speak Japanese?" is that I studied a bit in university, then studied a LOT in my free time, got slightly obsessed with kanji, spent a lot of time with Japanese-speaking friends, avoided English-only situations and people who wanted to learn English from me for free, took all the JLPTs, went to Japanese language school full-time for a bit, read books and manga and newspapers (even when I couldn't read them yet), and watched a lot of Japanese TV.

You don't need to be in Japan to do any of those things:

listen to Japanese audio all day

learn kanji on the bus (with Anki. Use anki. I wrote a post about that too)

find friends who speak Japanese

watch Japanese TV on Netflix (seriously, there's loads)

Being in Japan was great motivation to learn Japanese for me because I hate not understanding things and find it incredibly frustrating.

If you're in Japan and you want to know what's in your lunch or what that sign over there says or what the person next to you on the train is saying, you need to understand Japanese. That was a big push for me.

But you definitely don't need to live in Japan to get motivated.

I also started off working in English conversation school which was a good opportunity to listen to the kind of Japanese that five-year-olds speak. And one of the many good things about conversation school is you have the mornings off so I would get up and STUDY. Every day. Forever.

But I also probably have more free time now than I did in Japan.

You don't need to live in Japan to learn Japanese.

There are people all over the world who learn languages without living in the country the language comes from. I've met lots of people like this and had the pleasure of teaching some of them.

(The other thing I tell people when they ask how I learned Japanese is that I didn't learn it. I'm still learning.)

First published 17th Feb 2017

Updated 2nd March 2020

"How Did You Learn Kanji?"

I had a friend in 2011 who also lived in Japan and was also learning Japanese. Like me, he hoped to be fluent one day. I told him that I was going to learn all 2136 common-use kanji by making up a mnemonic story for each one. He laughed at me, of course. I don’t blame him.

But this slightly convoluted method is the thing that took my Japanese kanji knowledge from beginner to advanced.

So here is the story of how I studied kanji, some suggestions for kanji practice, plus some advice from another friend who took a totally different approach to me. I hope you’ll find it useful!

I had a friend in 2011 who also lived in Japan and was also learning Japanese. Like me, he hoped to be fluent one day. I told him that I was going to learn all 2136 common-use kanji by making up a mnemonic story for each one. He laughed at me, of course. I don’t blame him.

But this slightly convoluted method is the thing that took my Japanese kanji knowledge from beginner to advanced.

So here is the story of how I studied kanji, some suggestions for kanji practice, plus some advice from another friend who took a totally different approach to me. I hope you’ll find it useful!

Learning kanji takes time

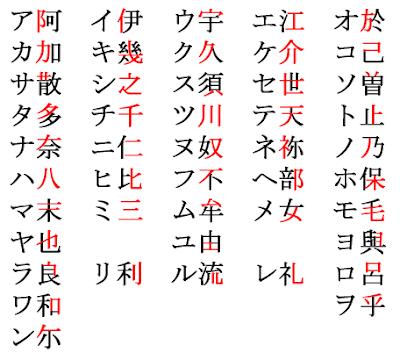

Written Japanese uses a mix of three “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji (Chinese characters).

Individual hiragana and katakana characters indicate sound only - the hiragana character あ makes the sound “a”, but it doesn’t have any meaning by itself. (Just like how the letter “B” doesn’t have any meaning by itself - it’s just a sound).

Kanji, on the other hand, indicate meaning as well as sound. For example, the kanji 木 means “tree”; 重 means “heavy”.

To read Japanese fluently, a student must be able to understand at least 2000 kanji. There is even an official list of the 2136 kanji that all Japanese children learn by the end of secondary school, called the jōyō kanji (常用漢字, meaning “regular-use kanji”).

The task of learning at least 2000 kanji is a major undertaking - even for Japanese people. That’s why students in Japan continue learning the jōyō kanji right up until the end of high school. And traditional methods of learning kanji tend to focus on rote memorisation, which is very inefficient.

The Heisig Method

When I got serious about learning kanji, in 2010, I did a bit of googling and stumbled across people talking about “the Heisig method”. This is the kanji study method introduced by James W. Heisig in his popular (and somewhat controversial) book ‘Remembering the Kanji I: A complete course on how not to forget the meaning and writing of Japanese characters’.*

The Heisig approach can be summed up as follows:

1) Learn the meaning of kanji

2) Learn the meaning of radicals

3) Memorise how to write kanji by making up descriptive mnemonic stories

You’ll note that reading kanji (how to pronounce them) does not feature on this list.

1) Learn the meaning of kanji

Heisig argues that before learning the readings of any kanji characters, it is more efficient to first learn the meanings. To this end, he gives each kanji an English keyword. For example, the kanji character 行 means “go”, so Heisig gives it the English keyword “going”.

By learning the meanings of kanji, the learner can guess at unfamiliar words.

I got to show off this ability years later in Okinawa, when my good friend Karli and I were looking at some artefact:

“What’s it made of?” she asked.

“I think it’s ivory.”

“Fran, why the hell do you know the Japanese word for ‘ivory’?”

“I don’t,” I said, pointing at the sign which had the word 象牙 on it. “But this one (象) "means ‘elephant’, and this one (牙) means ‘tusk’.”

2) Learn radicals

Heisig also puts a lot of focus on learning radicals - small parts which make up kanji. (He calls them “primitive elements”, but radicals is a more commonly-used term).

Radicals are the building blocks of kanji, and by learning to identify these constituent parts, you can “unpick” new and unfamiliar characters. Knowledge of radicals is also very helpful for looking up kanji in a dictionary.

For example, the kanji 明 (meaning “bright”) is made up of the two smaller parts 日 (“sun“) and 月 (“moon”). If the SUN and the MOON appeared in the sky together, that’d be pretty BRIGHT, right?

3) Make mnemonics

Using these radicals, Heisig argues that by making vivid and memorable stories, you can remember even complex kanji easily.

A common and simple example of a kanji mnemonic is 男, the character for “man”. The top half of this kanji is 田 “rice field“, and the bottom half is 力, “power”. So here’s the image: A MAN is someone who uses POWER in the RICE FIELD.

(If you’re not great at making up mnemonics, you can do what I did and copy other people’s funny stories from the Kanji Koohii website).

4) Practice writing by hand - from memory

Heisig says that in order to learn to read and recognise kanji characters, you should practise writing them. But rather than just copying them out endlessly, you need to use the power of active recall. He tells the student to use flashcards to test yourself on your ability to write the character from memory.

So for instance, on the front of the flashcard you have the word “man”, and then you recall the story ("oh yes, the POWER 力 in the RICE FIELD 田”) and write the kanji out from memory: 男.

The controversial part is the suggestion that you should do all of this work - make up 2000+ mnemonic stories, and learn to handwrite each kanji from memory - before learning how to read (i.e. pronounce) any of the kanji.

In practice, most students will be studying Japanese at the same time. (Who’s using the Heisig method to learn kanji, but not also learning the Japanese language? Nobody, I reckon.)

Combining the Heisig method with Anki

Heisig’s book was first published in 1977, so he suggests using paper flashcards. But the method really comes into its own when you use it with a flashcard app. I’l talk about Anki here because it’s the app I used.

Anki is a flashcard app that uses the principle of spaced repetition to make practising with flashcards as efficient as possible. Put simply, spaced repetition means the app decides when you need to see a flashcard next, based on how recently you got it right.

I used Anki for years, both for vocabulary practice and for kanji writing practice. It’s actually the reason I got a smartphone, in 2011.

You can make your own flashcard decks (a “deck” is what Anki calls a set of cards) with Anki, or you can download decks that other people have made. I used a deck that someone else made, but I edited it a bit.

On the front of the each card, I had the Heisig keyword. In this case, Heisig’s keyword is “eat”. This is a good keyword, as the kanji 食 means “eating” or “foodstuff”, and 食べる (taberu) is a verb meaning “to eat”. So, the idea is that you see the word “eat” and have to remember how to write the kanji:

How this works in practice

I probably practised writing kanji like this every day for about 15 minutes, for about a year and a half in 2010-2011. Essentially, that’s how I learned to write Japanese.

And by learning the meanings of kanji, suddenly all those signs and labels all around me (I was living in Japan by this time) started to have meaning.

Outside my flat there was a sign with the word 歩行者 on it. I knew that 歩 meant “walk”, 行 meant “go”, and 者 meant “person”. That’s how I learned that 歩行者 means “pedestrian”. I didn’t know how to read it aloud, but I knew what it meant.

The school that I worked at was an eikaiwa gakkou, an English conversation school. On the front of the school was the word 英会話. I knew that 英 could mean “English”, 会 meant “meet”, and 話 meant “talk”. I also knew that the character 英 could be read as ei, because it was in the word 英語 (eigo, the English language). And that 話 could be read as wa, because it was at the end of 電話 (denwa, telephone). So from this I could guess that 英会話 was ei-something-wa… and I knew the word eikaiwa (English conversation), so I asked my boss if 英会話 was “eikaiwa” - yes.

I was vegetarian when I first moved to Japan, so I spent some time scouring packages in supermarkets to work out whether I could eat things or not. I knew that the radical 月 could mean “meat” or “flesh”, and I knew that 豕 meant “pig”, so I could guess that 豚 was probably “pork” or “pig”. I didn’t know the word for pig, or the word for pork. But I could guess that I probably didn’t want to eat something with 豚 in it.

In other words, the Heisig method works - when combined with other Japanese study.

(Incidentally, I don’t “teach” Heisig because it’s a bit weird, and not for everyone. But I don’t teach kanji through rote memorisation either. I use an integrated approach - I want students to learn the meaning of individual kanji, and the readings of whole words, and to learn kanji in context as much as possible. But I still think that Heisig is a great self-study method, and if you’re interested, you should check out his book*).

Post-Heisig

As my Japanese got better, I no longer associated the kanji with English keywords. When I saw the kanji 食 I’d think of the meaning - something to do with eating or food - but not necessarily Heisig’s keyword. So later, on the front of each card, I added an example word containing the kanji, which is written in hiragana. In this case, the word is たべる (taberu; to eat), and to test myself, I have to write out the word 食べる (i.e., not just the individual kanji):

I also have the stroke order on the back of the card, so that I can check straight away if the stroke order I wrote out is correct or not. I added these by screenshotting the stroke order diagram in takoboto, the dictionary app I use on my phone.

(I used to be a bit lazy about stroke order, but since I started teaching Japanese I have spent some time correcting my bad habits).

The stroke order diagram is good for checking that you’re handwriting the kanji in the correct way, too. A common mistake learners make is copying typeface fonts, but many kanji look quite different when handwritten to how they look in type.

In December 2019, I decided to dust off this (very neglected) Anki deck and do some handwriting practice, every day for a month. For twenty minutes every day, I’d go through flashcards and test myself on whether I could handwrite the kanji.

I really enjoyed the routine of practising kanji again. I find kanji practice surprisingly relaxing. I mentioned this to some students, and they (well some of them anyway!) said they find kanji writing practice relaxing, even meditative. Little and often is probably key.

Find something you enjoy, and do it every day forever

Years later, I was out for dinner with an American friend in Japan. We were looking at the kanji-filled handwritten menu, and I realised that his Japanese reading was really quick - much faster than mine. “How did you learn to read kanji?” I asked him.

“Er, I dunno. Just, reading books I guess? For, like, years.”

It probably doesn’t matter too much how you study kanji. To be honest, I’m not sure that the Heisig method is better than any other. It worked for me, but if you put the time in, there are other methods of learning kanji that might work just as well.

The key thing is to find something that works for you, and spend a little time on it every day. And if your friends laugh at you, try and ignore them! One day they might be asking you how you did it.

Related posts

Links

Links with an asterisk* are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

Why Does The Japanese Language Have So Many Alphabets?

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

Until the 1st or 2nd century, Japan had no writing system. Then, sometime before 500AD, kanji - Chinese characters - made its way to Japan from China (probably via Korea).

These characters were originally used for their meaning only - they weren't used to write native Japanese words.

↓ And at that time, Japanese writing looked like this. Look, it looks like Chinese!

(Image Source - Nihon Shoki, Wikipedia)

But it was inconvenient not being able to write native Japanese words down, and so people began to use kanji to represent the phonetic sounds of Japanese words, not only the meaning. This is called manyougana and is the oldest native Japanese writing system.

For example, in manyougana the word asa (morning) was written 安佐 (that's a kanji for the “a” sound - 安 - and another for the “sa” sound - 佐). These characters indicate the sound of the word - “asa” - but not its meaning.

In modern Japanese we'd use 朝, the kanji that means "morning" for asa. This character shows its meaning AND its sound.

The problem was, manyougana used multiple kanji for each phonetic sound - over 900 characters for the 90 phonetic sounds in Japanese - so it was inefficient and time-consuming.

Gradually, people began to simplify kanji characters into simpler characters - that's where hiragana and katakana came from.

Katakana means "broken kana" or "fragmented characters". It was developed by monks in the 9th century who were annotating Chinese texts so that Japanese people could read them. So katakana was really an early form of shorthand.

Each katakana character comes from part of a kanji: for example, the top half of the kanji 呂 became katakana ロ (ro), and the left side of the kanji 加 became katakana カ (ka).

↓ Each katakana comes from part of a kanji.

(Source - Katakana origins, Wikipedia)

Women in Japan, on the other hand, wrote in cursive script, which was gradually simplified into hiragana. That's why hiragana looks all loopy and squiggly. Like katakana, hiragana characters don't have meaning - they just indicate sound.

↓ How kanji (top) evolved into manyougana (middle in red), and then hiragana (bottom).

(Source - Hiragana evolution, Wikipedia)

Because it was simpler than kanji, hiragana was accessible for women who didn't have the same education level as men. The 11th-century classic The Tale of Genji was written almost entirely in hiragana, because it was written by a female author for a female audience.

Modern Japanese writing uses all three of these “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji - often all mixed up in the same sentence.

What would 12th-century people in Japan think of my students, 900 years later, learning hiragana as they take their first steps into the Japanese language?

First published 28th Oct 2016

Updated 27th Jan 2020

Even More Japanese Loanwords From Languages That Aren't English

Last time I talked about Japanese loanwords - words that Japanese has “borrowed” from other languages - which come from languages other than English.

But there are also some tricky loanwords that look and sound like they came from English - but they didn’t!

Last time I talked about Japanese loanwords - words that Japanese has “borrowed” from other languages - which come from languages other than English.

But there are also some tricky loanwords that look and sound like they came from English - but they didn’t!

Challenge time!

Don’t be fooled. These loanwords look and sound a bit like they came from English - but they didn’t! Can you guess what languages these loanwords come from?

(Hint: not English!)

Koohii コーヒー coffee

Zero ゼロ zero

Pompu ポンプ pump

Botan ボタン button

Koppu コップ cup

Sarada サラダ salad

Kokku コック cook

Scroll down for the answers…!

The Answers:

Did you guess what non-English languages these loanwords come from?

Koohii コーヒー coffee - Portuguese

Zero ゼロ zero - French

Pompu ポンプ pump - Dutch; Flemish

Botan ボタン button - Portuguese

Koppu コップ cup - Dutch; Flemish

Sarada サラダ salad - Portuguese

Kokku コック cook - Dutch; Flemish

Students often ask why there are so many Portuguese and Dutch loanwords in Japanese. Words from these two languages have been used as loanwords in Japanese since the 16th and 17th centuries, when both countries established trade with Japan.

So, just because that katakana word you’ve learned looks like English, doesn’t mean it came from English!

Japanese Loanwords From Languages That Aren't English

Modern Japanese contains a lot of loan words - words that Japanese has “borrowed” from other languages. These words are typically written in the katakana “alphabet”.

Many of these words come from English - but not all.

Modern Japanese contains a lot of loan words - words that Japanese has “borrowed” from other languages. These words are typically written in the katakana “alphabet”.

Many of these words come from English - but not all.

So if you’ve been wondering what happened to the “t” sound at the end of the Japanese word resutoran (レストラン, restaurant), it was never there in the first place - because that loanword didn’t come from English. It came from French.

And my students sometimes ask me why the Japanese word for salad is sarada (サラダ), not “sarado”. That’s because sarada comes not from the Engish word “salad”, but from the Portuguese “salada”.

It’s good to know which loanwords didn’t come from English - and it's interesting to know what languages they come from - so you can remember how to pronounce them correctly.

Hopefully this will help you remember that it’s resutoran (not resutoranto!)

Quiz time!

How many of these Japanese loanwords do you know? Can you guess the meaning of any?

Rentogen レントケン

Piero ピエロ

Arubaito アルバイト

Piiman ピーマン

Ruu ルー

Esute エステ

Ikura イクラ

Noruma ノルマ

Karuta カルタ

Sukoppu スコップ

Igirisu イギリス

⇩ HINT: Japan believes in calling a スコップ a スコップ

The Answers:

Rentogen レントケン X-ray (from German)

Piero ピエロ clown (French)

Arubaito アルバイト part time job (German)

Piiman ピーマン peppers [the vegetable] (French)

Run ルー roux sauce [or, more commonly, a block of Japanese curry mix used to make curry sauce] (French)

Esute エステ aesthetic salon i.e. beauty salon (French)

Ikura イクラ salmon roe (Russian)

Noruma ノルマ quota (Russian)

Karuta カルタ Japanese playing cards (Portuguese)

Sukoppu スコップ spade (Dutch; Flemish)

Igirisu イギリス the U.K. (Portuguese)

Pan パン bread (Portuguese)

So, next time you see a katakana word you don't recognise, don't despair - it might not have originated from a language you speak!

First published May 2016

Updated 9th Jan 2020

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.