Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Five (and a Half) Apps to Get You Started Learning Japanese

Do you take your smartphone with you wherever you go? If the answer’s “yes”, congratulations! You have a powerful language-learning tool in your pocket at all times.

Supplementing what you're learning in class with apps and games is fun, easy, and cheap. But with so many applications out there, here do you know where to start?

So in no particular order, here are five and a half brilliant apps to get you started on the magical quest that is learning Japanese.

Do you take your smartphone with you wherever you go? If the answer’s “yes”, congratulations! You have a powerful language-learning tool in your pocket at all times.

Supplementing what you're learning in class with apps and games is fun, easy, and cheap. But with so many applications out there, here do you know where to start?

So in no particular order, here are five and a half brilliant apps to get you started on the magical quest that is learning Japanese.

1. Hiragana Pixel Party

If you want to read Japanese, you need to start by learning hiragana, the 46 characters that make up Japanese's basic 'alphabet'. And there are a plethora of apps to help you on your way. The problem is...well, lots of them are quite boring. Hiragana Pixel Party breaks that mould with an addictive little rhythm game that is actually good fun.

As kana characters appear on screen, you listen to the sound of each character, and then tap in time with the beat to successfully jump over obstacles. So it's a musical running game that also happens to be teaching you to read the characters.

I'm going to go out a limb here and say Hiragana Pixel Party is probably the most fun you can have learning hiragana (and katakana). Unless you don't like chiptunes, I guess...?

Hiragana Pixel Party: iOS | Nintendo Switch! and Steam

2. Mindsnacks

Mindsnacks is a series of smartphone learning games for different foreign languages. You start with a couple of games, and unlock more by completing tasks.

The games themselves are pretty fun, and easy to get the hang of. You spell vocab words in hiragana by tapping on squeaky little chipmunks in the right order, or match words and meanings by spinning the cubes of a totem pole. So, it's basically vocab matching, gamified.

Did I mention it has chipmunks? Naww ↓

You can also choose between romaji, kana, and kanji when learning words, which is a nice touch.

The only downside with Mindsnacks (apart from the fact it's for iPhone/iPad only - sorry...) is that I do find it a bit repetitive. To try it as a beginner, I downloaded the Mandarin app too, and felt like I was being tested too many times on the same words before the app was satisfied that I'd "mastered" them.

It is a fun set of games, though, and worth checking out. You can try out one lesson for free - to unlock all 50 lessons is £3.99.

Learn Japanese by Mindsnacks: iOS

3. Dr. Moku

Dr. Moku claims to be able to teach you hiragana and katakana in one hour, through mnemonics and quizzes. I like the illustrations - they're cute (and sometimes creepy, but in a funny way, which is helpful for committing the images to memory).

↓ Creepy and cute.

4. Hiragana Memory Hint

Less of a game and more of a learning aid, this app from the Japan Foundation Kansai has mnemonics and varied quizzes to test yourself on the reading and sound of the hiragana. There's a separate app for katakana too - but the best part though is that they're both FREE!

Hiragana Memory Hint: iOS | Android

Katakana Memory Hint: iOS | Android

5. Tae Kim

Tae Kim's grammar guide is a comprehensive reference to (you guessed it) Japanese grammar. It started life as a website before taking flight in app form for iOS. Having this app on your phone is like carrying around a searchable textbook that you can look things up on at any time. And it's free! Yay!

Don't be scared by the kanji - you can tap on underlined words and the reading and English meaning appear in a nifty pop-up.

↓ It's pretty nifty generally, actually.

What I like about the guide is that it attempts to explain grammar "not from English but from a Japanese point of view". So, instead of translating Japanese sentences into natural, long-winded English, it tells us what the sentence is saying (and no more).

↓ You go Tae Kim!

You probably won't want to read it from start to finish (although some people do), but it's great for double-checking something you're not sure on, or for when you need a quick refresher. For looking things up on the go you can't get much better than this.

Tae Kim's Guide to Learning Japanese: iOS

Number 5½...

I read in the front of a dictionary once (a paperback one) that all you need to learn a language is a good teacher and a good dictionary. And that's why essential app number 5 and a half is...a dictionary!

Sure, you could just fire up a web-based dictionary like jisho.org - but if you've got the space for it, having offline access to a dictionary is more useful than you might think. It won't eat all your data, and you can still use it on top of Mt. Fuji.

There are loads and loads of free Japanese dictionaries for smartphones. Imi wa is deservedly popular for iPhone, or you could try JED or Akebi on Android. The best thing to do is just download as many free ones as you can, figure which one you like and delete all the others.

Just don't use google translate to do your homework, unless you want a string of garbled directly-translated text and a disappointed teacher.

And finally...

Apps won't teach you everything - you're not going to get much speaking practice from playing with hiragana all day - but they're a great way to add in a bit of extra practice and complement your language learning.

So there you have it - five-and-a-half apps to get you started on the road to learning Japanese! What do you reckon of my selection? What did I miss? I'd love to know what you think, so please let me know in the comments!

First published November 05, 2015

Updated October 03, 2018

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 8) - O-settai, or, "I'll treasure this tissue case"

Near Kumadani-ji, temple number 8, we had stopped in front of some glorious cherry blossom, and I got chatting to two older gentlemen who were walking the trail. One told me he had never spoken to a gaijin-san, foreigner, before.

(The cynic in me wonders if that’s really true, or if by “foreigner” he meant “white person”…)

We took some pictures in front of the cherry blossom, and walked up the hill together.

Further up the road, a lady came out of her house and gave us some hard-boiled sweets ...

“Wait here. I want to give you o-settai.”

Near Kumadani-ji, temple number 8, we had stopped in front of some glorious cherry blossom, and I got chatting to two older gentlemen who were walking the trail. One told me he had never spoken to a gaijin-san, foreigner, before.

(The cynic in me wonders if that’s really true, or if by “foreigner” he meant “white person”…)

We took some pictures in front of the cherry blossom, and walked up the hill together.

Further up the road, a lady came out of her house and gave us some hard-boiled sweets.

The sweets were a form of o-settai, small gifts given to walking pilgrims. Traditionally, pilgrims didn't carry money, so they were helped along their way by gifts of food, lodging and other acts of generosity from local people.

“Wait here,” she said when she saw me, “I have something else for you.”

She came back with a colourful children’s section of the newspaper – a visual guide to the Shikoku pilgrimage, with readings for the kanji characters written above in hiragana.

It was several years old. I wondered if she had been saving it for a passing foreigner.

I briefly considered attempting to refuse it: I already had a good map, and I can read kanji, so I didn't need a children’s guide. The next non-Japanese person she met might have more use for it.

But explaining that would have felt arrogant, and you’re supposed to accept o-settai graciously, so I thanked her, and we went on our way.

The next day, I heard it again. “Wait here. I want to give you o-settai.”

I was alone this time. I had stopped to rest on a fading bench outside a children’s centre, and was enjoying my first iced can coffee in a couple of years.

There were no houses on this side of the road, but an elderly lady had come out of her house and crossed the busy road to strike up a conversation with me.

She referred to herself in the third person as obaa-chan, grandmother. She was 82.

The obaa-chan had walked the whole pilgrimage twice, she told me, and had hoped to do it a third time.

“But I’m too old to walk it again now, so I give o-settai instead.”

She went back into the house, and I saw her in the front room with a cardboard box. She did look frail. I wondered if I should follow her over the road so she didn't have to cross it again, but I didn't want to intrude.

“I must have given out hundreds of these,” she said proudly when she came back.

Inside the box were dozens of cotton tissue cases, in all different colours, each with a small packet of tissues inside.

“Did you make these?”

“Of course! Choose one.”

I picked out one with black cats sitting by front doors.

“Thank you very much. I’ll take good care of it.”

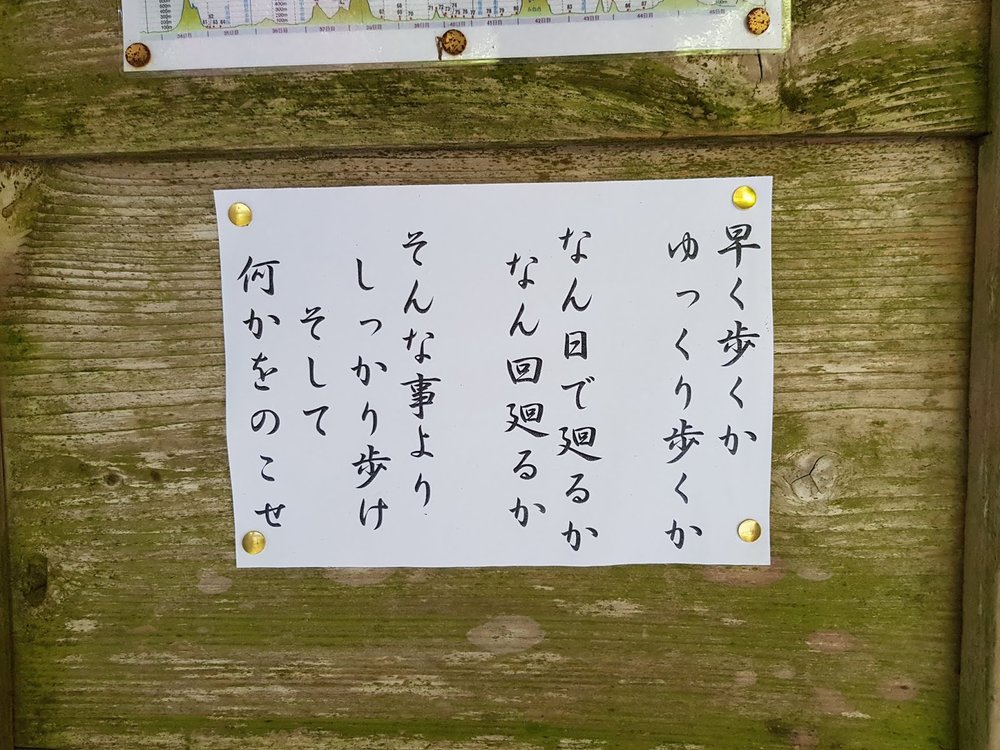

The tissue case had a secondary compartment, and inside that was a paper insert. It was a photocopy of handwriting - guidance for living a good life. “I like these words, so I included them too,” she added.

“When you use it, please remember the 82-year-old obaa-chan from Shikoku.”

The tissue case has travelled 6000 miles with me back to England, but I haven’t opened the tissues yet. I’m know she wanted me to use it; but I just want to keep it safe.

It smells faintly of incense.

I think about the obaa-chan sewing tissue cases. I wonder if she waits by the window in pilgrimage season – spring and autumn – waiting for walkers to pass by.

She gave me much more than a tissue case. She made me feel welcome, and showed me kindness. Perhaps that’s what o-settai is…? It’s about human connection. It’s not about things, it’s about people.

I’ll treasure this tissue case, I promise.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage(Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

And also: "I treasure this pen case"

"I treasure this pen case"

“I treasure this mechanical pencil.”

(Applause)

One of the interesting things about working as an Assistant Language Teacher (ALT) in Japan is that you get to see the kind of English taught in Japanese state schools.

Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s bad; but in my opinion it’s always interesting, and you’re always learning something …

“I treasure this mechanical pencil.”

(Applause)

One of the interesting things about working as an Assistant Language Teacher (ALT) in Japan is that you get to see the kind of English taught in Japanese state schools.

Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s bad; but in my opinion it’s always interesting, and you’re always learning something.

I worked as an ALT for a year in Nagoya, before I started teaching and translating Japanese.

On this particular day I was scheduled to be in class with 13 and 14-year-olds who were giving speeches about a special personal item. The Japanese teacher of English wanted the native English speaker (that’s me!) to assess the kids’ speaking.

I quite liked helping out with speaking assessments - most students enjoy it, and their talks were often funny and creative.

This day was a bit different, though. As the students started to give their talks, I realised all the speeches ended in the same, slightly odd, distinctive phrase:

“I treasure this mechanical pencil.”

“I treasure this eraser.”

“I treasure this pen case.”

(ペンケース (pen keesu), incidentally, is a perfectly good Japanese loanword, but it’s not the English word for “pencil case”, or not where I’m from anyway).

I looked at the textbook. The example from their textbooks was a boy talking about an ice hockey jersey his father had given him, and ended with “I treasure this jersey.”

Ah.

A large number of the students had either:

1) not understood that they were supposed to choose a special and important possession

or

2) forgotten to do the assignment altogether, and hastily cobbled together a speech based on an stationery item they had nearby.

Incidentally, the Japanese translation in their textbook for “I treasure this jersey” (a fairly uncommon English phrase, I’d say) is このジャージを大切にしています (kono jaaji wo taisetsu ni shite imasu).

〜を大切にします (_____wo taisetsu ni shimasu) is a nice, natural sounding way to say you care about or value something in Japanese:

持ち物を大切にする mochimono o taisetsu ni suru - to look after your belongings

体を大切にして下さい karada o taisetsu ni shite kudasai - please take care of yourself

So, at least I learned some Japanese that day, even if I had to sit through thirty speeches about treasured erasers.

What’s your treasure? I’ll tell you about mine next week!

Summer Barbecue Party 2018! (Or, "Where's The Corn?")

Last year, I tried to break up the long months of summer by inviting my students for an August barbecue.

This year I've been teaching my Summer Courses, so summer hasn't been the long lesson-free months I'd got used to.

(This is a good thing. I like teaching, and I think my students are really enjoying their summer classes too.)

I still wanted to have a student party though! ...

Last year, I tried to break up the long months of summer by inviting my students for an August barbecue.

This year I've been teaching my Summer Courses, so summer hasn't been the long lesson-free months I'd got used to.

(This is a good thing. I like teaching, and I think my students are really enjoying their summer classes too.)

I still wanted to have a student party though! It was a lot of fun. Here are some pictures from our sunny day on the beach:

Setting up. I wanted to make it easy to find us this time, so I invested in this excellent Japan flag.

Beer with somewhat controversial Japan-inspired ingredients. (I liked the packaging more than the taste, myself...)

Joe brought home-made burgers again!

(Not everyone was here yet when I took this group photo, and it looks like I forgot to take another one - sorry!)

Home-made beer! Arigatou gozaimasu!

CORN!

If you came to the barbecue last year (or read my blog post) you'll remember that accidentally everyone brought corn. This year, I think we went the other way, and for a while it looked like there would be no corn!

Luckily, David saved the day by turning up with corn. Hurray!

After an afternoon on the beach, clean up time and a trip to the recycling!

Some of us decanted to a pub, to talk about pub quizzes, parkour and the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage.

Thanks for coming! Roll on next year :o)

"Two beers, please!"

I don't speak Portuguese. But here's what I learned last week on holiday in Lisbon …

I don't speak Portuguese. But here's what I learned last week on holiday in Lisbon:

how to say "two beers, please"

it's olá, not hola.

a "thank you" with a smile is worth three "thank you"s with no smile

i need to add "this please" to my Survival Japanese course as a central key phrase.

learning words in a new language is a lot easier when you can read the words already (hurray for the roman alphabet!)

you can delete social media apps for a week and put the out-of-office on, and the world will not end

sometimes a very short blog post is fine

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

"Kyūkei shimashou" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called kyūkeijo 休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to strike up a conversation …

"

Ky

ū

kei shimashou

" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called

kyūkeijo

休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to

.

Luckily for me, the bit of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail I walked this spring had interesting and varied rest stops throughout. So what kind of places are used as

kyūkeijo

?

1) Temple outbuildings

On the first day I walked with another pilgrim, who I'd met at temple number 1. We stopped around midday, at a

ky

ū

keijo

in a temple outhouse building.

The women inside offered us tea and sweets, and in exchange we handed them

osamefuda

(納め札),

slips of paper with your name and a message, on which pilgrims carry instead of money

.

(...traditionally, I mean. Most modern pilgrims carry money too now.)

I was grateful to receive the tea and sweets, but even more grateful to have the opportunity to chat with these friendly women, who said they had lived in Shikoku all their lives.

They told me their ages (in their 70s and 80s), and that some of them had walked the 750-mile pilgrimage three or four times in their lifetimes.

2) Private houses

Some rest stops are out the front of a private home. The owners prepare tea or hot water each morning, and leave it out for visiting walkers:

I sat at this one alone and ate my packed lunch. It was a baking hot day, so I was glad to be out of the sunshine.

Both these

ky

ū

keijo

had signs explaining that the snacks and drinks are offered for free as

o-settai

(お接待), small gifts given to walking pilgrims to help them on their way.

3) Vending-machine seating

Usually, at the temple itself there will be a vending machine or two, with seating next to it.

It can be seen as impolite to eat or drink while walking in Japan, so vending machines often have seats next to them.

You can enjoy your snack first, and then walk around afterwards. Remember, rest is important!

I sat at this one and had a can of iced coffee:

I also spotted this set of hardwood chairs in one temple rest area, which look like they're set up to accommodate a whole coach trip:

4) Outdoor rest stops

In the mountains, a clearing with a place to sit down can be a really nice surprise. This one below had obviously taken some work to create, being in the middle of the forest. And it was labeled (in English!) as a "lounge", which I thought was just great.

It clearly is a lounge. It just happen to be outside!

5) Wooden huts

There are also small rest houses maintained by community groups. These are good for getting out of the sun (or the rain!)

This one had a formidable list of rules about not leaving rubbish behind, and stating that it was only for the use of walking pilgrims. It was on a main road in a town, so I guess they'd had problems before.

Anyway, it seems the rules are being followed these days, as the house was spotless:

I had some tea and a delicious fresh orange, read the extensive rules, and wrote in the guestbook.

Towards the end of my walk, I spotted another outdoor rest stop. This one was also purpose-built, with concrete table and seating, and a great view.

What I liked was that people had added extra seating - the sofa and chair, presumably from someone's home:

But the best type of rest stop is when you get to your lodging for the night, and can put your feet up.

それでは、休憩しましょう!

Sore dewa, kyūkei shimashou!

So,

let's take a break!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move. They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly …

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move.

They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly. I waved the little grey bag with its digital camera inside. "

KAMERA

!"

I still couldn't make out their faces, but I thought I saw a glimmer of recognition. One of the pair walked towards me, and it was only then that I saw her face.

"I thought you were Japanese," she said, and I heard a European accent I couldn't place.

"I thought

you

were Japanese," I said.

"We're French," she offered.

"Ah." I paused. "Um, bonjour?"

We walked together a little bit, and then I left them at a rest stop.

I bumped into them again later in the week, at breakfast in the inn we were staying at. The women was showing the owner a piece of paper, and he was squinting at it.

They seemed to be having some difficulty, so I offered to help.

I squinted at the piece of paper too, and was suddenly transported back to year 6, learning about French cursive in class.

There was the name of a youth hostel in the next town over, and a short message underneath. It was all in romaji (Japanese written in the roman alphabet), but in looping, cursive letters:

futari desu. kyou, yoyaku onegai shimasu.

"For two people. A reservation for tonight, please."

I read it aloud to the owner, who promptly got on the phone and made a reservation for them.

"Your note was fine," I told them. "I think he just didn't have his glasses."

Or perhaps he couldn't read their cursive? I didn't say that though.

I wondered later how the rest of their trip went. They seemed to be having a great time.

There's no right or wrong way to walk the Shikoku pilgrimage. And it's possible to travel in Japan without any Japanese language at all. But if you can learn even a bit of the language, you'll have a richer experience, I think.

And you'll understand when someone's trying to tell you you've dropped your camera.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.