Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Mini-interview with Elly Darrah of Ippo Ippo Japanese

Elly is the Edinburgh-based Japanese teacher behind Ippo Ippo Japanese. Did you know, Ippo Ippo means “step by step” in Japanese? I think that’s a great approach to learning Japanese - one step at a time.

In this mini interview I asked Elly some questions about the Japanese language, and we talked about tips for learners who are just getting started.

Elly is the Edinburgh-based Japanese teacher behind Ippo Ippo Japanese. Did you know, Ippo Ippo means “step by step” in Japanese? I think that’s a great approach to learning Japanese - one step at a time.

In this mini interview I asked Elly some questions about the Japanese language, and we talked about tips for learners who are just getting started.

Have you lived in Japan before? Do you have any favourite memories you think of at this time of year?

Yes, I previously lived in Hyogo (near Kobe) and Osaka, and this time of year brings back a lot of memories of Japanese spring. In particular, I remember getting the train from Hyogo to Osaka and seeing cherry blossoms all along the river when I was on my way to a hanami (cherry blossom viewing) picnic with friends. I actually miss riding the train in Japan quite a lot - at least out of rush hour!

Do you have a favourite kanji?

There are so many kanji I love for so many different reasons! However, one I’ve recently been reminded of is 傘 (umbrella) because it visually reminds me of what it means: people (人) being protected from the rain.

What tips do you have for anyone thinking of starting to learn Japanese?

My biggest tip is to not worry about doing things the “right” way. You can spend hours and hours looking for the perfect textbook or perfect study method, but the main factor in improving in a language is simply spending time on it. That said, if your study method of choice turns out not to motivate you, don’t be afraid to change things up and find something you enjoy. For me, I (unexpectedly) got really into Japanese dramas and music. Keep exploring and you’ll find something that grabs your interest too!

Elly and I are co-hosting Explore Japanese, an online event all about getting started in Japanese. Click here to find out more -29th March or 6th April.

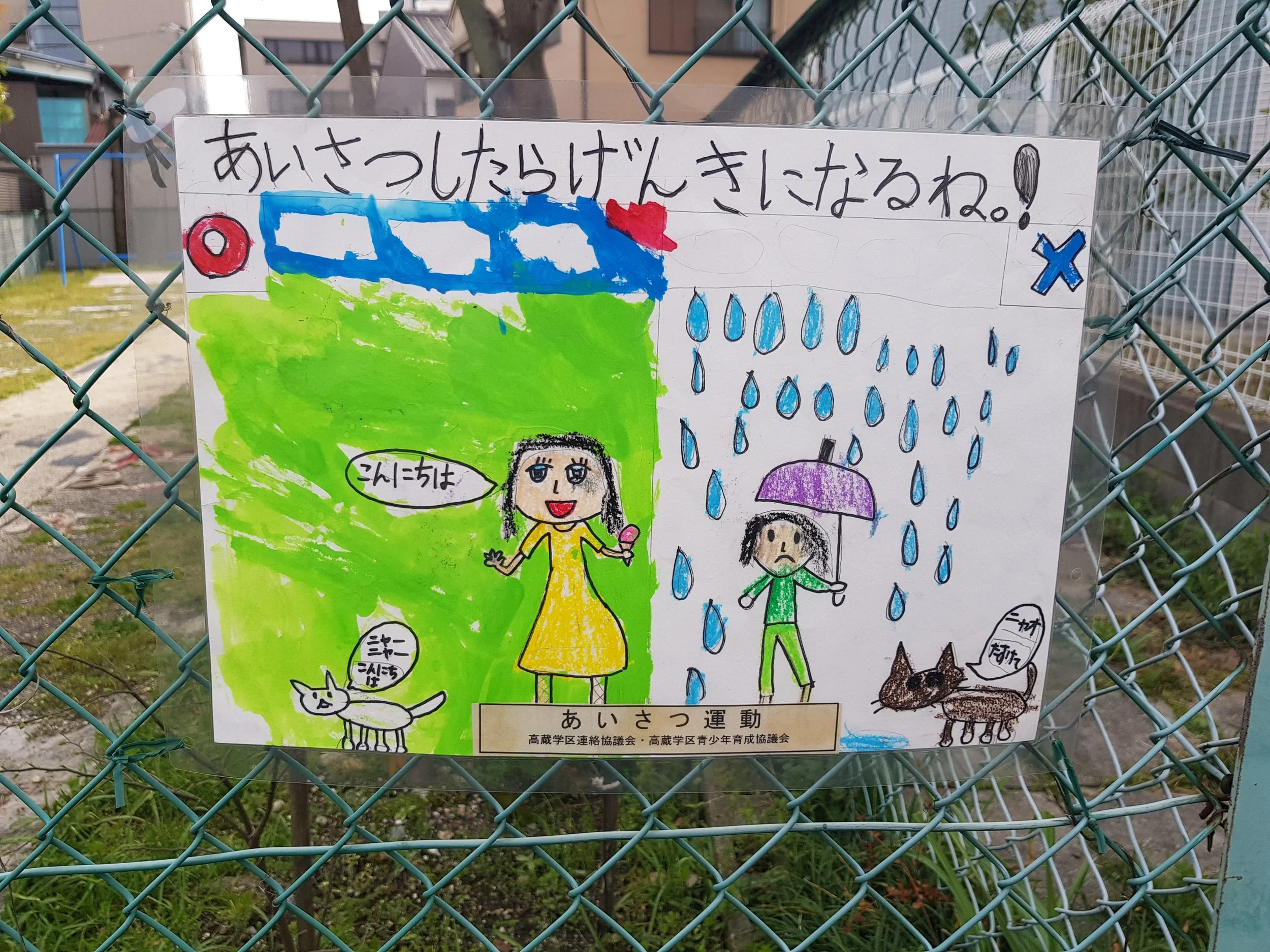

Say Good Morning to the Room - The Importance of Aisatsu (Greetings) in Japan

By the entrance to the conference room, there was a flip chart with a message: “Please sign in here, and then go through the door and say good morning to the room”.

“OHAYO GOZAIMAAASU!” I yelled. (GOOD MORNING!)

We had practiced this yesterday. “In Japanese workplaces,” they told us, “you must greet the room enthusiastically when entering.”

As I took my seat, I noticed that some trainees had been given a piece of card by staff as they entered.

By the entrance to the conference room, there was a flip chart with a message: “Please sign in here, and then go through the door and say good morning to the room”.

“OHAYO GOZAIMAAASU!” I yelled. (GOOD MORNING!)

We had practiced this yesterday. “In Japanese workplaces,” they told us, “you must greet the room enthusiastically when entering.”

As I took my seat, I noticed that some trainees had been given a piece of card by staff as they entered.

A member of staff took to the podium. “Well done everybody on your amazing greetings this morning. You sounded so energetic and loud!

“Those of you who’ve been given a card, your greetings were not quite as genki (energetic) as they could have been. Have a think about that.”

I was at a week’s training for my new job as Assistant Language Teacher (ALT) in Nagoya.

I wasn’t sure about the method of handing out cards to let some people know their greetings weren’t up to regulation enthusiasm standards. But I got the message - greetings are important.

Fast-forward three months, and I was teaching in Junior High school. Every morning, I’d take my shoes off in the entryway to the school and change into my indoor slippers. I’d slide open the door to the staffroom, and greet the room: “OHAYO GOZAIMAAASU!”

“Ohayo gozaimasu!” other teachers would say back, at varying volumes and with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Good morning!

A few minutes later, the vice principal passed by my desk:

フラン先生は、挨拶がいつも元気ですね。

Fran-sensei wa, aisatsu ga itsumo genki desu ne.

(“Your morning greetings are always so cheerful!”)

そうですか。ありがとうございます。

Sou desu ka. Arigatou gozaimasu.

(“Is that so? Thank you.”)

I smiled all day.

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 8) - O-settai, or, "I'll treasure this tissue case"

Near Kumadani-ji, temple number 8, we had stopped in front of some glorious cherry blossom, and I got chatting to two older gentlemen who were walking the trail. One told me he had never spoken to a gaijin-san, foreigner, before.

(The cynic in me wonders if that’s really true, or if by “foreigner” he meant “white person”…)

We took some pictures in front of the cherry blossom, and walked up the hill together.

Further up the road, a lady came out of her house and gave us some hard-boiled sweets ...

“Wait here. I want to give you o-settai.”

Near Kumadani-ji, temple number 8, we had stopped in front of some glorious cherry blossom, and I got chatting to two older gentlemen who were walking the trail. One told me he had never spoken to a gaijin-san, foreigner, before.

(The cynic in me wonders if that’s really true, or if by “foreigner” he meant “white person”…)

We took some pictures in front of the cherry blossom, and walked up the hill together.

Further up the road, a lady came out of her house and gave us some hard-boiled sweets.

The sweets were a form of o-settai, small gifts given to walking pilgrims. Traditionally, pilgrims didn't carry money, so they were helped along their way by gifts of food, lodging and other acts of generosity from local people.

“Wait here,” she said when she saw me, “I have something else for you.”

She came back with a colourful children’s section of the newspaper – a visual guide to the Shikoku pilgrimage, with readings for the kanji characters written above in hiragana.

It was several years old. I wondered if she had been saving it for a passing foreigner.

I briefly considered attempting to refuse it: I already had a good map, and I can read kanji, so I didn't need a children’s guide. The next non-Japanese person she met might have more use for it.

But explaining that would have felt arrogant, and you’re supposed to accept o-settai graciously, so I thanked her, and we went on our way.

The next day, I heard it again. “Wait here. I want to give you o-settai.”

I was alone this time. I had stopped to rest on a fading bench outside a children’s centre, and was enjoying my first iced can coffee in a couple of years.

There were no houses on this side of the road, but an elderly lady had come out of her house and crossed the busy road to strike up a conversation with me.

She referred to herself in the third person as obaa-chan, grandmother. She was 82.

The obaa-chan had walked the whole pilgrimage twice, she told me, and had hoped to do it a third time.

“But I’m too old to walk it again now, so I give o-settai instead.”

She went back into the house, and I saw her in the front room with a cardboard box. She did look frail. I wondered if I should follow her over the road so she didn't have to cross it again, but I didn't want to intrude.

“I must have given out hundreds of these,” she said proudly when she came back.

Inside the box were dozens of cotton tissue cases, in all different colours, each with a small packet of tissues inside.

“Did you make these?”

“Of course! Choose one.”

I picked out one with black cats sitting by front doors.

“Thank you very much. I’ll take good care of it.”

The tissue case had a secondary compartment, and inside that was a paper insert. It was a photocopy of handwriting - guidance for living a good life. “I like these words, so I included them too,” she added.

“When you use it, please remember the 82-year-old obaa-chan from Shikoku.”

The tissue case has travelled 6000 miles with me back to England, but I haven’t opened the tissues yet. I’m know she wanted me to use it; but I just want to keep it safe.

It smells faintly of incense.

I think about the obaa-chan sewing tissue cases. I wonder if she waits by the window in pilgrimage season – spring and autumn – waiting for walkers to pass by.

She gave me much more than a tissue case. She made me feel welcome, and showed me kindness. Perhaps that’s what o-settai is…? It’s about human connection. It’s not about things, it’s about people.

I’ll treasure this tissue case, I promise.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage(Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

And also: "I treasure this pen case"

What is Community Interpreting and Why Does it Matter?

The dentist talked for a long time, in Japanese I didn't understand, pointing and waving his hands at the X-ray on the wall. I was completely lost.

After he'd talked for about five minutes, my Japanese boss translated for me: "He says you need to fix this tooth."

That's it? I thought. The dentist had been talking for ages. He can't possibly have only said "you need to fix this tooth".

The dentist talked for a long time, in Japanese I didn't understand, pointing and waving his hands at the X-ray on the wall. I was completely lost.

After he'd talked for about five minutes, my Japanese boss translated for me: "He says you need to fix this tooth."

That's it? I thought. The dentist had been talking for ages. He can't possibly have only said "you need to fix this tooth".

The first year I was in Japan I had a lot of dental work done.

I broke a tooth (ouch!) and then it kept breaking. It was unpleasant.

I'm very grateful that my Japanese boss came to these appointments with me. And when he couldn't come, his mum would come with me. It was really kind of them.

But I usually didn't really understand what was going on. Imagine if I'd had access to a professional interpreter instead?

I often have interpreting on the brain. My "other job" (i.e. what I do when I don't have my Step Up Japanese hat on) is working in the offices of a community interpreting service here in Brighton.

So what is Community Interpreting?

Interpreting is listening to what is said in one language, and communicating the meaning in another language. And Community Interpreting (as opposed to conference interpreting, or interpreting in business meetings etc) basically exists to enable people to access public services.

Community Interpreters attend medical, legal and housing appointments with people who have limited English, helping them to understand fully what's going on.

Using a professional interpreter guarantees that interpreting is accurate and unbiased.

The interpreter's job is to remain impartial in a three-way conversation between the person with the language need (in Japan, that was me), and the professional they're seeing (the dentist).

Ah yes, my Japanese dentist.

After a while I could understand enough to attend the appointments by myself. Sometimes, I could tell the dentist was using simple language, to ensure I understood. That was kind of him.

But some medical messages are too important to be said in simple language.

So how would my experiences in Japan have been different if I'd had access to a professional interpreter?

It would have been empowering to make decisions about my medical care, without having to ask my boss's mum. I'm sure I would have felt a little less scared of the dentist waving his hands around, too.

If you'd like to learn more about Community Interpreting from a global perspective, you should check out Madeline Vadkerty's talk "Making the World a Better Place As an Interpreter" at next week's Women in Language event.

I'm really looking forward to hearing Madeline speak about her experiences as a Community Interpreter, helping asylum seekers and survivors of torture to rebuild their lives.

(I'll be speaking too - eek!)

Your ticket for Women in Language gets you access to the entire 4-day event with over 25 awesome women speaking.

Click here to get your ticket before the event begins on Thursday 8th March 2018.

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.