Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

How Do You Say "Nice to Meet You" in Japanese?

Hurray! You've met another Japanese-speaking person. Time to introduce yourself.

But how do you say "It's really nice to meet you" in Japanese? The first phrase you'll want is:

はじめまして。Hajimemashite. "Nice to meet you"

Hajimemashite literally means "we are meeting for the first time". So you can only use it the first time you meet someone.

Hurray! You've met another Japanese-speaking person. Time to introduce yourself.

But how do you say "Pleased to meet you" in Japanese?

The first phrase you'll want is:

はじめまして。

Hajimemashite.

"Nice to meet you"

Hajimemashite (almost literally) means "we are meeting for the first time". So you can only use it the first time you meet someone.

The other super-useful phrase is:

よろしくおねがいします。

Yoroshiku onegai shimasu.

"Please be kind to me."

Yoroshiku onegai shimasu is hard to translate, but means something like "please be kind to me".

It means that you are looking forward to having a good relationship with someone.

Shop “Nice To Meet You” Japanese necklaces (Step Up Japanese x designosaur):

Make it more polite

Add douzo to make your greeting more polite:

どうぞよろしくおねがいします。

Douzo yoroshiku onegai shimasu.

"Nice to meet you" (polite & a bit formal)

You could also say:

お会いできてうれしいです。

O-ai dekite ureshii desu.

"I'm happy to meet you." (more polite & formal)

or even:

お会いできて光栄です

O-ai dekite kouei desu.

"I'm honoured to meet you." (even more polite & formal)

Keep it casual

If you don't feel like being so polite, you could also say:

どうぞよろしく。

Douzo yoroshiku.

"Nice to meet you" (a bit more casual)

よろしくね。

Yoroshiku ne.

"Nice to meet you" (very casual)

It's good to be nice-mannered when you meet new people though, right?

"Nice to meet you too!"

Last but not least, when someone says yoroshiku onegaishimasu, you can add the feeling of "me too!" by replying with kochira koso ("me too!"):

こちらこそ宜しくお願いします。

Kochira koso yoroshiku onegaishimasu.

"No, I'm pleased to meet you." / "The pleasure is mine."

Now, go and find someone new to speak to, and tell them how pleased you are to meet them.

Yoroshiku ne!

Shop “Nice To Meet You” Japanese necklaces (Step Up Japanese x designosaur):

Updated 26th Oct 2020

"How Did You Learn Kanji?"

I had a friend in 2011 who also lived in Japan and was also learning Japanese. Like me, he hoped to be fluent one day. I told him that I was going to learn all 2136 common-use kanji by making up a mnemonic story for each one. He laughed at me, of course. I don’t blame him.

But this slightly convoluted method is the thing that took my Japanese kanji knowledge from beginner to advanced.

So here is the story of how I studied kanji, some suggestions for kanji practice, plus some advice from another friend who took a totally different approach to me. I hope you’ll find it useful!

I had a friend in 2011 who also lived in Japan and was also learning Japanese. Like me, he hoped to be fluent one day. I told him that I was going to learn all 2136 common-use kanji by making up a mnemonic story for each one. He laughed at me, of course. I don’t blame him.

But this slightly convoluted method is the thing that took my Japanese kanji knowledge from beginner to advanced.

So here is the story of how I studied kanji, some suggestions for kanji practice, plus some advice from another friend who took a totally different approach to me. I hope you’ll find it useful!

Learning kanji takes time

Written Japanese uses a mix of three “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji (Chinese characters).

Individual hiragana and katakana characters indicate sound only - the hiragana character あ makes the sound “a”, but it doesn’t have any meaning by itself. (Just like how the letter “B” doesn’t have any meaning by itself - it’s just a sound).

Kanji, on the other hand, indicate meaning as well as sound. For example, the kanji 木 means “tree”; 重 means “heavy”.

To read Japanese fluently, a student must be able to understand at least 2000 kanji. There is even an official list of the 2136 kanji that all Japanese children learn by the end of secondary school, called the jōyō kanji (常用漢字, meaning “regular-use kanji”).

The task of learning at least 2000 kanji is a major undertaking - even for Japanese people. That’s why students in Japan continue learning the jōyō kanji right up until the end of high school. And traditional methods of learning kanji tend to focus on rote memorisation, which is very inefficient.

The Heisig Method

When I got serious about learning kanji, in 2010, I did a bit of googling and stumbled across people talking about “the Heisig method”. This is the kanji study method introduced by James W. Heisig in his popular (and somewhat controversial) book ‘Remembering the Kanji I: A complete course on how not to forget the meaning and writing of Japanese characters’.*

The Heisig approach can be summed up as follows:

1) Learn the meaning of kanji

2) Learn the meaning of radicals

3) Memorise how to write kanji by making up descriptive mnemonic stories

You’ll note that reading kanji (how to pronounce them) does not feature on this list.

1) Learn the meaning of kanji

Heisig argues that before learning the readings of any kanji characters, it is more efficient to first learn the meanings. To this end, he gives each kanji an English keyword. For example, the kanji character 行 means “go”, so Heisig gives it the English keyword “going”.

By learning the meanings of kanji, the learner can guess at unfamiliar words.

I got to show off this ability years later in Okinawa, when my good friend Karli and I were looking at some artefact:

“What’s it made of?” she asked.

“I think it’s ivory.”

“Fran, why the hell do you know the Japanese word for ‘ivory’?”

“I don’t,” I said, pointing at the sign which had the word 象牙 on it. “But this one (象) "means ‘elephant’, and this one (牙) means ‘tusk’.”

2) Learn radicals

Heisig also puts a lot of focus on learning radicals - small parts which make up kanji. (He calls them “primitive elements”, but radicals is a more commonly-used term).

Radicals are the building blocks of kanji, and by learning to identify these constituent parts, you can “unpick” new and unfamiliar characters. Knowledge of radicals is also very helpful for looking up kanji in a dictionary.

For example, the kanji 明 (meaning “bright”) is made up of the two smaller parts 日 (“sun“) and 月 (“moon”). If the SUN and the MOON appeared in the sky together, that’d be pretty BRIGHT, right?

3) Make mnemonics

Using these radicals, Heisig argues that by making vivid and memorable stories, you can remember even complex kanji easily.

A common and simple example of a kanji mnemonic is 男, the character for “man”. The top half of this kanji is 田 “rice field“, and the bottom half is 力, “power”. So here’s the image: A MAN is someone who uses POWER in the RICE FIELD.

(If you’re not great at making up mnemonics, you can do what I did and copy other people’s funny stories from the Kanji Koohii website).

4) Practice writing by hand - from memory

Heisig says that in order to learn to read and recognise kanji characters, you should practise writing them. But rather than just copying them out endlessly, you need to use the power of active recall. He tells the student to use flashcards to test yourself on your ability to write the character from memory.

So for instance, on the front of the flashcard you have the word “man”, and then you recall the story ("oh yes, the POWER 力 in the RICE FIELD 田”) and write the kanji out from memory: 男.

The controversial part is the suggestion that you should do all of this work - make up 2000+ mnemonic stories, and learn to handwrite each kanji from memory - before learning how to read (i.e. pronounce) any of the kanji.

In practice, most students will be studying Japanese at the same time. (Who’s using the Heisig method to learn kanji, but not also learning the Japanese language? Nobody, I reckon.)

Combining the Heisig method with Anki

Heisig’s book was first published in 1977, so he suggests using paper flashcards. But the method really comes into its own when you use it with a flashcard app. I’l talk about Anki here because it’s the app I used.

Anki is a flashcard app that uses the principle of spaced repetition to make practising with flashcards as efficient as possible. Put simply, spaced repetition means the app decides when you need to see a flashcard next, based on how recently you got it right.

I used Anki for years, both for vocabulary practice and for kanji writing practice. It’s actually the reason I got a smartphone, in 2011.

You can make your own flashcard decks (a “deck” is what Anki calls a set of cards) with Anki, or you can download decks that other people have made. I used a deck that someone else made, but I edited it a bit.

On the front of the each card, I had the Heisig keyword. In this case, Heisig’s keyword is “eat”. This is a good keyword, as the kanji 食 means “eating” or “foodstuff”, and 食べる (taberu) is a verb meaning “to eat”. So, the idea is that you see the word “eat” and have to remember how to write the kanji:

How this works in practice

I probably practised writing kanji like this every day for about 15 minutes, for about a year and a half in 2010-2011. Essentially, that’s how I learned to write Japanese.

And by learning the meanings of kanji, suddenly all those signs and labels all around me (I was living in Japan by this time) started to have meaning.

Outside my flat there was a sign with the word 歩行者 on it. I knew that 歩 meant “walk”, 行 meant “go”, and 者 meant “person”. That’s how I learned that 歩行者 means “pedestrian”. I didn’t know how to read it aloud, but I knew what it meant.

The school that I worked at was an eikaiwa gakkou, an English conversation school. On the front of the school was the word 英会話. I knew that 英 could mean “English”, 会 meant “meet”, and 話 meant “talk”. I also knew that the character 英 could be read as ei, because it was in the word 英語 (eigo, the English language). And that 話 could be read as wa, because it was at the end of 電話 (denwa, telephone). So from this I could guess that 英会話 was ei-something-wa… and I knew the word eikaiwa (English conversation), so I asked my boss if 英会話 was “eikaiwa” - yes.

I was vegetarian when I first moved to Japan, so I spent some time scouring packages in supermarkets to work out whether I could eat things or not. I knew that the radical 月 could mean “meat” or “flesh”, and I knew that 豕 meant “pig”, so I could guess that 豚 was probably “pork” or “pig”. I didn’t know the word for pig, or the word for pork. But I could guess that I probably didn’t want to eat something with 豚 in it.

In other words, the Heisig method works - when combined with other Japanese study.

(Incidentally, I don’t “teach” Heisig because it’s a bit weird, and not for everyone. But I don’t teach kanji through rote memorisation either. I use an integrated approach - I want students to learn the meaning of individual kanji, and the readings of whole words, and to learn kanji in context as much as possible. But I still think that Heisig is a great self-study method, and if you’re interested, you should check out his book*).

Post-Heisig

As my Japanese got better, I no longer associated the kanji with English keywords. When I saw the kanji 食 I’d think of the meaning - something to do with eating or food - but not necessarily Heisig’s keyword. So later, on the front of each card, I added an example word containing the kanji, which is written in hiragana. In this case, the word is たべる (taberu; to eat), and to test myself, I have to write out the word 食べる (i.e., not just the individual kanji):

I also have the stroke order on the back of the card, so that I can check straight away if the stroke order I wrote out is correct or not. I added these by screenshotting the stroke order diagram in takoboto, the dictionary app I use on my phone.

(I used to be a bit lazy about stroke order, but since I started teaching Japanese I have spent some time correcting my bad habits).

The stroke order diagram is good for checking that you’re handwriting the kanji in the correct way, too. A common mistake learners make is copying typeface fonts, but many kanji look quite different when handwritten to how they look in type.

In December 2019, I decided to dust off this (very neglected) Anki deck and do some handwriting practice, every day for a month. For twenty minutes every day, I’d go through flashcards and test myself on whether I could handwrite the kanji.

I really enjoyed the routine of practising kanji again. I find kanji practice surprisingly relaxing. I mentioned this to some students, and they (well some of them anyway!) said they find kanji writing practice relaxing, even meditative. Little and often is probably key.

Find something you enjoy, and do it every day forever

Years later, I was out for dinner with an American friend in Japan. We were looking at the kanji-filled handwritten menu, and I realised that his Japanese reading was really quick - much faster than mine. “How did you learn to read kanji?” I asked him.

“Er, I dunno. Just, reading books I guess? For, like, years.”

It probably doesn’t matter too much how you study kanji. To be honest, I’m not sure that the Heisig method is better than any other. It worked for me, but if you put the time in, there are other methods of learning kanji that might work just as well.

The key thing is to find something that works for you, and spend a little time on it every day. And if your friends laugh at you, try and ignore them! One day they might be asking you how you did it.

Related posts

Links

Links with an asterisk* are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

A Japan Pub Quiz!

I wrote a little bit about my Japanese volunteers who come to help out at class and with events and workshops.

But I’m also helped enormously at Step Up Japanese by my students, who organise events, give me great ideas, and share helpful feedback on how to make class better.

I wrote a little bit about my Japanese volunteers who come to help out at class and with events and workshops.

But I’m also helped enormously at Step Up Japanese by my students, who organise events, give me great ideas, and share helpful feedback on how to make class better.

Huge thanks to STEP 4 student Sheen-san for organising this fantastic Japan-themed quiz for us last week. And thank you all for coming!

またしましょうね。Let’s do it again sometime!

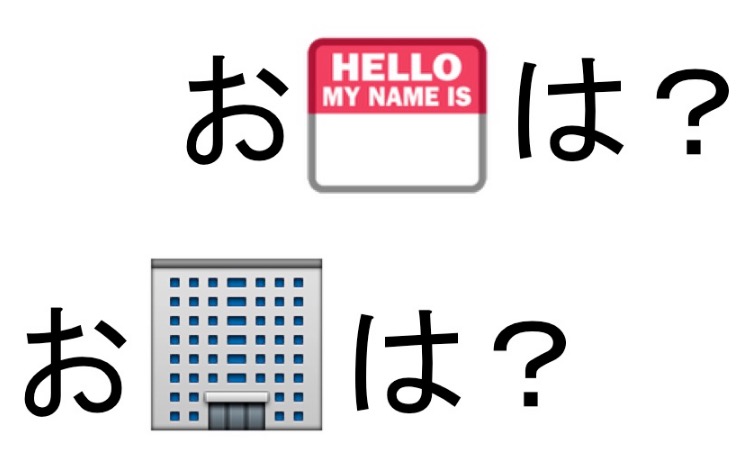

Three Ways You Should Be Using The Japanese Honorific お (Part 1)

Fairly early on in your Japanese-learning journey, you'll learn some set phrases like:

o-genki desu ka? (How are you?)

o-shigoto wa nan desu ka? (What's your job?)

Usually I teach that the “o” in o-genki desu ka makes the question more polite. This is true, but it’s not the whole story.

Fairly early on in your Japanese-learning journey, you'll learn some set phrases like:

o-genki desu ka? (How are you?)

o-shigoto wa nan desu ka? (What's your job?)

Usually I teach that the “o” in o-genki desu ka makes the question more polite. This is true, but it’s not the whole story.

Honorific o (or sometimes go) is basically used for three things:

1) Being polite about someone else

It's good to be more polite about other people than you are about yourself, right?

So when you're speaking about someone else, there are certain words that get an o (or go) on the front:

o-shigoto お仕事 (your honourable job)

o-sumai お住まい (your respected abode)

Like in these common Japanese questions:

o-namae wa? お名前は? (What is your esteemed name?)

o-genki desu ka お元気ですか。 (Are you [person I respect] well?)

When you talk about yourself, however, don't use o or go: just namae, genki, kazoku, shigoto. You can't talk about your own o-namae or go-kazoku!

2) Sounding more polite generally

Adding o to a word can make your speech sound more polished. Words that don’t necessarily need o, but often get it, include:

sushi / o-sushi (sushi)

kome / o-kome (rice)

sake / o-sake (rice wine)

With these words, either way is fine. If you're trying to speak politely you might want to use the 'o' version.

Unlike the first group, this kind of o isn’t anything to do with whose sushi or sake it is. It just sounds a bit nicer if you stick the o on there. Like you’re respecting the rice.

3) Some words just always have it

So, some words need o/go only when you're talking about someone else. Others can either have it or not.

There's a third category, too - words where the o/go has been subsumed into the word completely, and can't really be detached:

Gohan (ご飯, meal/cooked rice) always needs go - there's no unadorned word "han" for rice (although there presumably was at some point.)

O-cha (お茶, tea) pretty much always gets o, as does o-kane (お金, money). Just cha or kane sounds quite rough.

Words like this don't really belong to the "o/go is polite" rule of thumb. It's best just to learn them as whole words.

O or go?

Generally, words of Chinese origin take the prefix go, instead of o:

go-kazoku (your esteemed family)

go-kyouryoku (your noble cooperation)

go-ryoushin (your respected parents)

There are some exceptions, though… but more on that next time.

First published (as “Hey! What’s That お Doing There?”) in December 2015

Updated 21 December, 2018

Are Loanwords "Real" Japanese?

Shortly after I started studying Japanese at university, I got an email from a friend in Sweden:

“How’s it going? Learned any more ‘Japanese words’ like camera and video?”

I’d copy-pasted her some of the "new words" from my textbook. There was a list of them - words like kamera (camera) and rajio (radio)…

I felt like I was cheating. These aren’t Japanese words!

Or are they?

Shortly after I started studying Japanese at university, I got an email from a friend in Sweden:

“How’s it going? Learned any more ‘Japanese words’ like camera and video?”

I’d copy-pasted her some of the "new words" from my textbook. There was a list of them - words like kamera (camera) and rajio (radio)…

I felt like I was cheating. These aren’t Japanese words!

Or are they?

Japanese has LOADS of these loanwords - words borrowed from other languages. And two things often happen when a foreign word gets used as a loanword:

Extra vowel sounds

All Japanese syllables - except ん (n) - end in a vowel sound. That means when we convert a foreign word into Japanese, some rogue vowels get thrown in there too:

hot dogホットドッグ hotto doggu

world cup ワールドカップ waarudo kappu

2. Abbreviations

Adding in all those extra vowels makes these loanwords in Japanese much longer than their English equivalents, so they often get shortened:

suupaamaaketto スーパーマーケット

↓

suupaa スーパー (supermarket)

depaatomento sutoa デパートメントストア

↓

depaato デパート (department store)

↓ Spot the katakana loanword(s)!

Sometimes the first bit of both words gets used:

dejitaru kamera デジタルカメラ

↓

dejikame デジカメ (digital camera)

paasonaru konpuuta パーソナルコンピュータ

↓

pasokon パソコン (personal computer)

...which I hope you'll agree are some of the most adorable words ever.

These loanwords, therefore, can teach us a bit about Japanese pronunciation, as well as the Japanese love of abbreviations. I was wrong about them not being "Japanese words", though - depaato and pasokon are definitely Japanese words. Japan may have borrowed them, but it's not giving them back.

Is learning loanwords cheating? What's your favourite Japanese loanword? Let me know in the comments!

First published December 2015

Updated December 7, 2018

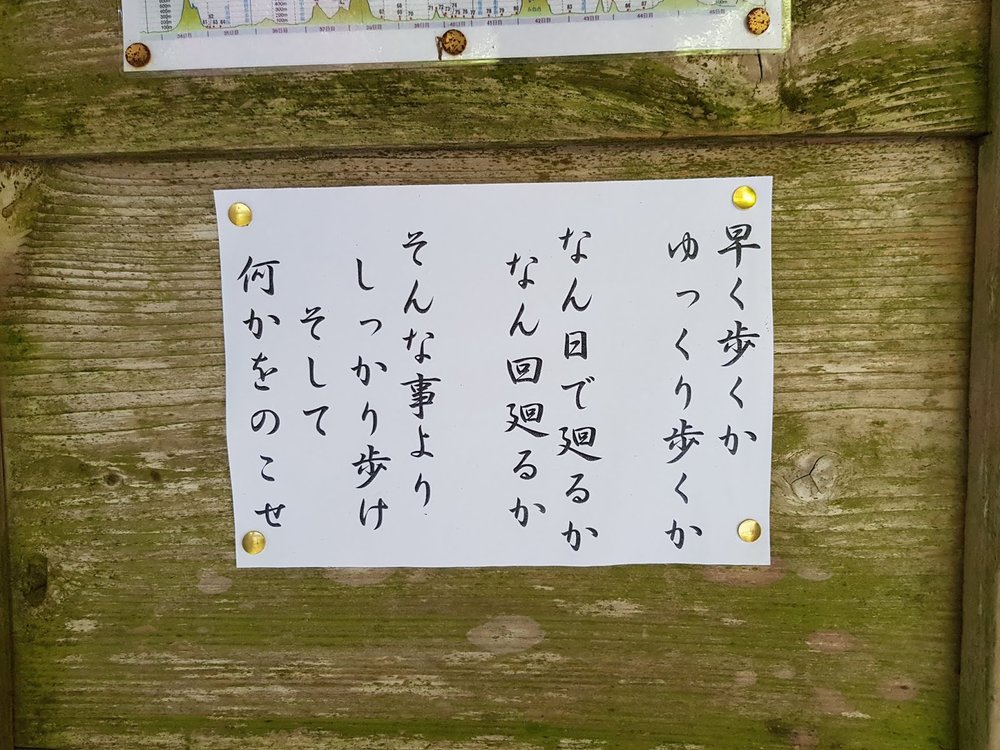

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

"Kyūkei shimashou" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called kyūkeijo 休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to strike up a conversation …

"

Ky

ū

kei shimashou

" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called

kyūkeijo

休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to

.

Luckily for me, the bit of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail I walked this spring had interesting and varied rest stops throughout. So what kind of places are used as

kyūkeijo

?

1) Temple outbuildings

On the first day I walked with another pilgrim, who I'd met at temple number 1. We stopped around midday, at a

ky

ū

keijo

in a temple outhouse building.

The women inside offered us tea and sweets, and in exchange we handed them

osamefuda

(納め札),

slips of paper with your name and a message, on which pilgrims carry instead of money

.

(...traditionally, I mean. Most modern pilgrims carry money too now.)

I was grateful to receive the tea and sweets, but even more grateful to have the opportunity to chat with these friendly women, who said they had lived in Shikoku all their lives.

They told me their ages (in their 70s and 80s), and that some of them had walked the 750-mile pilgrimage three or four times in their lifetimes.

2) Private houses

Some rest stops are out the front of a private home. The owners prepare tea or hot water each morning, and leave it out for visiting walkers:

I sat at this one alone and ate my packed lunch. It was a baking hot day, so I was glad to be out of the sunshine.

Both these

ky

ū

keijo

had signs explaining that the snacks and drinks are offered for free as

o-settai

(お接待), small gifts given to walking pilgrims to help them on their way.

3) Vending-machine seating

Usually, at the temple itself there will be a vending machine or two, with seating next to it.

It can be seen as impolite to eat or drink while walking in Japan, so vending machines often have seats next to them.

You can enjoy your snack first, and then walk around afterwards. Remember, rest is important!

I sat at this one and had a can of iced coffee:

I also spotted this set of hardwood chairs in one temple rest area, which look like they're set up to accommodate a whole coach trip:

4) Outdoor rest stops

In the mountains, a clearing with a place to sit down can be a really nice surprise. This one below had obviously taken some work to create, being in the middle of the forest. And it was labeled (in English!) as a "lounge", which I thought was just great.

It clearly is a lounge. It just happen to be outside!

5) Wooden huts

There are also small rest houses maintained by community groups. These are good for getting out of the sun (or the rain!)

This one had a formidable list of rules about not leaving rubbish behind, and stating that it was only for the use of walking pilgrims. It was on a main road in a town, so I guess they'd had problems before.

Anyway, it seems the rules are being followed these days, as the house was spotless:

I had some tea and a delicious fresh orange, read the extensive rules, and wrote in the guestbook.

Towards the end of my walk, I spotted another outdoor rest stop. This one was also purpose-built, with concrete table and seating, and a great view.

What I liked was that people had added extra seating - the sofa and chair, presumably from someone's home:

But the best type of rest stop is when you get to your lodging for the night, and can put your feet up.

それでは、休憩しましょう!

Sore dewa, kyūkei shimashou!

So,

let's take a break!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move. They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly …

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!"

I shouted.

("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move.

They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!"

("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly. I waved the little grey bag with its digital camera inside. "

KAMERA

!"

I still couldn't make out their faces, but I thought I saw a glimmer of recognition. One of the pair walked towards me, and it was only then that I saw her face.

"I thought you were Japanese," she said, and I heard a European accent I couldn't place.

"I thought

you

were Japanese," I said.

"We're French," she offered.

"Ah." I paused. "Um, bonjour?"

We walked together a little bit, and then I left them at a rest stop.

I bumped into them again later in the week, at breakfast in the inn we were staying at. The women was showing the owner a piece of paper, and he was squinting at it.

They seemed to be having some difficulty, so I offered to help.

I squinted at the piece of paper too, and was suddenly transported back to year 6, learning about French cursive in class.

There was the name of a youth hostel in the next town over, and a short message underneath. It was all in romaji (Japanese written in the roman alphabet), but in looping, cursive letters:

futari desu. kyou, yoyaku onegai shimasu.

"For two people. A reservation for tonight, please."

I read it aloud to the owner, who promptly got on the phone and made a reservation for them.

"Your note was fine," I told them. "I think he just didn't have his glasses."

Or perhaps he couldn't read their cursive? I didn't say that though.

I wondered later how the rest of their trip went. They seemed to be having a great time.

There's no right or wrong way to walk the Shikoku pilgrimage. And it's possible to travel in Japan without any Japanese language at all. But if you can learn even a bit of the language, you'll have a richer experience, I think.

And you'll understand when someone's trying to tell you you've dropped your camera.

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.