Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

How to Read The Japanese News (Or Any Japanese Website!) with Rikaichan

When I first moved back to Brighton from Japan I had a lot of time on my hands. I also didn't have a job, so I was desperate for free Japanese reading material.

So I started borrowing Japanese books from the library.

This plan was not exactly a success. It turns out reading Twilight in Japanese is only slightly more entertaining than reading it in English.

But we are really lucky to live in a world where, if you have internet access, you can read just about anything you want in Japanese online. And the news is a great place to start.

When I first moved back to the UK from Japan I had a lot of time on my hands. I also didn't have a job, so I was desperate for free Japanese reading material.

So I started borrowing Japanese books from the library.

This plan was not exactly a success. It turns out reading Twilight in Japanese is only slightly more entertaining than reading it in English.

But we are really lucky to live in a world where, if you have internet access, you can read just about anything you want in Japanese online. And the news is a great place to start.

If you can't read fluently yet, looking at a page of Japanese text can be intimidating. You don't know the meaning of the word, or even how to sound it out.

You need a dictionary - a really smart free one like Rikaichan. Rikaichan is a browser add-on that works as a pop-up dictionary. I used it every day for years, and I love it. Let's take a look at how it works, and start reading the news!

How Rikaichan works

Here we are on the website of the Asahi Shimbun, one of Japan's largest national newspapers.

I hover the cursor over the word 音楽. Rikaichan's little blue pop up tells me the reading of the word (おんがく ongaku) and what it means - "music".

Rikaichan also shows us the dictionary entries for individual kanji (Chinese characters).

Here, it's showing 音, the first character in the word 音楽, and telling us that 音 means "sound".

Learn where words begin and end

Standard written Japanese doesn't have spaces between words so if you're looking at unfamiliar words, it can be hard to know where each word starts and finishes.

Rikaichan is pretty smart at doing that bit for you.

Here, in the below example, it knows that 九州 (Kyushu island) is one word, and 豪雨 (torrential rain) is the next, separate word.

How to get it

So that's what Rikaichan does. Here's how to get started with it!

1) Get the right browser

Rikaichan and its "little brother" Rikaikun are for the web browsers Firefox and Chrome. If you're not using one of those, you'll need to download the browser first.

It's worth it. I used Firefox religiously for years just so I could use Rikaichan to get my morning news.

As far as I know the add-on doesn't work on mobile, unfortunately. (There's a similar-looking app called Wakaru for iOS - if you've used it, let me know what you think.)

2) Install Rikaichan or Rikaikun

Which one do you need? Rikaichan and Rikaikun are the same add-on, but for Firefox and Chrome. So, download and install Rikaichan from the Mozilla add ons page, or Rikaikun from the Chrome Web Store.

3) Download a dictionary

Rikaichan needs a dictionary to pull readings and meanings from, so after you've installed the add-on, you'll be prompted to install at least one dictionary file. If English is your first language, you want the "Japanese - English" dictionary.

I recommend installing the "Japanese Names" dictionary too, so that Rikaichan can identify common names when they pop up. That way, it'll know that 中田 is Nakada, a common Japanese surname, and doesn't just mean "middle of the ricefield".

4) Turn Rikaichan on

You probably won't want Rikaichan on all the time. Sometimes you'll want to read without a dictionary, and sometimes you won't be reading Japanese. You can turn it off and on when you like. Turn Rikaichan on, and let's give it a go.

Read everything!

Years ago when I started using Rikaichan, I set myself a challenge to read one headline with it every day.

Next, I made myself read three headlines per day. Then five. Then the first paragraph of an article. Eventually I was reading entire news articles, and using the dictionary less and less.

These days I get the Asahi Shimbun news straight to my inbox, because I don't need to look up words often enough to use Rikaichan any more.

But it was a completely invaluable part of my language learning journey. And it's definitely more interesting than reading Twilight in Japanese.

Updated 23rd Oct 2020

A Year of Monthly Japanese Learning Challenges

How do you keep practising Japanese, even when it doesn’t seem relevant? How do you stay motivated, when your life and your motivations change?

At the beginning of 2019, I decided to set myself a series of monthly Japanese study challenges. I’d do one every other month, and blog about it.

In January, I tried to speak Japanese every day for a month. This was probably the hardest challenge, from a logistical perspective. I don’t live in Japan, and we don’t speak Japanese at home (much). At the time, I was also working another job three days a week, where I wasn’t using Japanese at all. So speaking Japanese every day was, quite literally, a challenge.

How do you keep practising Japanese, even when it doesn’t seem relevant? How do you stay motivated, when your life and your motivations change?

At the beginning of 2019, I decided to set myself a series of monthly Japanese study challenges. I’d do one every other month, and blog about it.

In January, I tried to speak Japanese every day for a month. This was probably the hardest challenge, from a logistical perspective. I don’t live in Japan, and we don’t speak Japanese at home (much).

At the time, I was also working another job three days a week, where I wasn’t using Japanese at all. So speaking Japanese every day was, quite literally, a challenge.

But this was a great start to the year and probably one of my favourite things I’ve done using Japanese. Plus, I got to eat katsu curry at cafe an-an in Portslade and chalk it up as Japanese practice:

I Tried to Speak Japanese Every Day for a Month (Without Being in Japan)

In March, I tried shadowing every day.

What is shadowing? Most people are familiar with “listen and repeat” in language learning contexts. You listen to a conversation line-by-line and repeat each sentence after the recording.

Shadowing is different from simple “listen and repeat” in that you start speaking while the person on the audio is still talking. The goal is to be able to produce the dialogue with perfect pronunciation, as close to the recorded audio as possible.

I really enjoyed this challenge, and I also discovered that you can practise shadowing (quietly) in hotel rooms, waiting rooms, and even on the bus.

What is Shadowing and Can it Improve Your Spoken Japanese? I Tried Shadowing Every Day for a Month

In May, I read Japanese books every day. This was really fun, too, and not so hard once I got into a routine. If you get in the habit of taking a book with you everywhere you go, reading every day is relatively easy:

How to Read More in Japanese – I Tried Reading in Japanese Every Day for a Month

In July, I decided to play Japanese video games every day for a month, because who says challenges have to be challenging?

I played Japanese video games for about 20 minutes a day for a month, and here’s what I learned: six reasons to play video games in a foreign language.

This is not a “how to” post. I’m not going to tell you how to “learn Japanese in a week just by playing video games” or to claim this is a “quick route to fluency” (it’s not, namely because there is no quick route to fluency, just an endless and potentially very enjoyable road trip).

Instead, I’m just going to share some reflections on the very fun experience that was playing Japanese video games every day.

How to Practise Japanese by Playing Video Games Every Day

(IMAGE SOURCE: NINTENDO)

In September, I tried to watch Japanese TV every day. This is where the monthly challenges really started to come unstuck. September was a busy month, and life got in the way.

I also discovered that when a challenge isn’t very challenging, I don’t personally find it very motivating!

One fantastic thing that came out of this experience, however, was the idea for my new course Learn Japanese with Netflix! … but then covid-19 happened, which meant the Netflix course only ran for a few weeks. I hope to run it, or a similar course, again in the future.

Watching Japanese TV Every Day for a Month (Or, What to Do When Things Don't Go To Plan)

After that I took a two month break, and then in December, I got well and truly back on the horse, and spent a month practising handwriting kanji from memory every day.

I really enjoyed the routine of practising kanji again. I find kanji practice surprisingly relaxing - and I mentioned this to some students, who also said they find kanji writing practice relaxing, even meditative. Little and often is probably key.

"How Did You Learn Kanji?"

What next?

The process of setting bi-monthly goals was a stimulating and enjoyable experience, and I might repeat it another year, but I’m not doing monthly challenges in 2020.

We’re a few months into 2020, and due to covid-19, this year is already shaping up to be significantly more challenging than 2019.

2020 has already proved to be a year of radical change, for students at Step Up Japanese as well as for people all over the world. In March 2020 I moved all lessons online - another new challenge, but an enjoyable one.

I hope you stay healthy and safe throughout 2020, and that if Japanese study is a part of your life at the moment, that you enjoy it and have fun. And if life gets in the way sometimes….that’s okay too.

日本語教室で多読のコースを開いてみたイギリス人日本語教師の感想

私はどっちかといえばもの静かなほうだと思いますが、日本語を教える時はうるさい時もあります。授業では歌を歌ったり、盆踊りを踊ったり、にぎやかなゲームをしたりしています。隣の部屋で会議を行おうとしていた人たちに「少し静かにしてくれませんか」と注意されたこともあります。

でも、2018年に私はとても静かな日本語の授業を開きました。この授業では、生徒は主に一人で黙って勉強していました。

私はその授業の「先生」だったけれど、私も一人で手作りの絵本を読んでいて、時々生徒が大丈夫かを確かめるために目を上げただけ。

これは「多読」です。普通の日本語の授業と全然違う読解の学習法です。

(英語版はこちら Click here to read in English)

私はどっちかといえばもの静かなほうだと思いますが、日本語を教える時はうるさい時もあります。授業では歌を歌ったり、盆踊りを踊ったり、にぎやかなゲームをしたりしています。隣の部屋で会議を行おうとしていた人たちに「少し静かにしてくれませんか」と注意されたこともあります。

でも、2018年に私はとても静かな日本語の授業を開きました。この授業では、生徒は主に一人で黙って勉強していました。

私はその授業の「先生」だったけれど、私も一人で手作りの絵本を読んでいて、時々生徒が大丈夫かを確かめるために目を上げただけ。

これは「多読」です。普通の日本語の授業と全然違う読解の学習法です。

多読とは、文字通りたくさん読むことです。簡単な本をたくさん読んで、外国語を身につける方法です。多読では、今の勉強のレベルより少し簡単なレベルの本を読みながら、新しい言葉や表現や文法を自然に習うことができます。

私は、多読の「授業」を開くのにかなり緊張していました。生徒が読んでいる間、私は先生としてどうすればいいかな?そこに座るだけ?生徒は一人で読むなら家ですればいいんじゃない?いったい誰が「静かに一人で読む」クラスに参加したいのだろう?

ネットでいろいろ調べて、東京にある多読を支援する団体である「NPO多言語多読」から多読の本を取り寄せました。

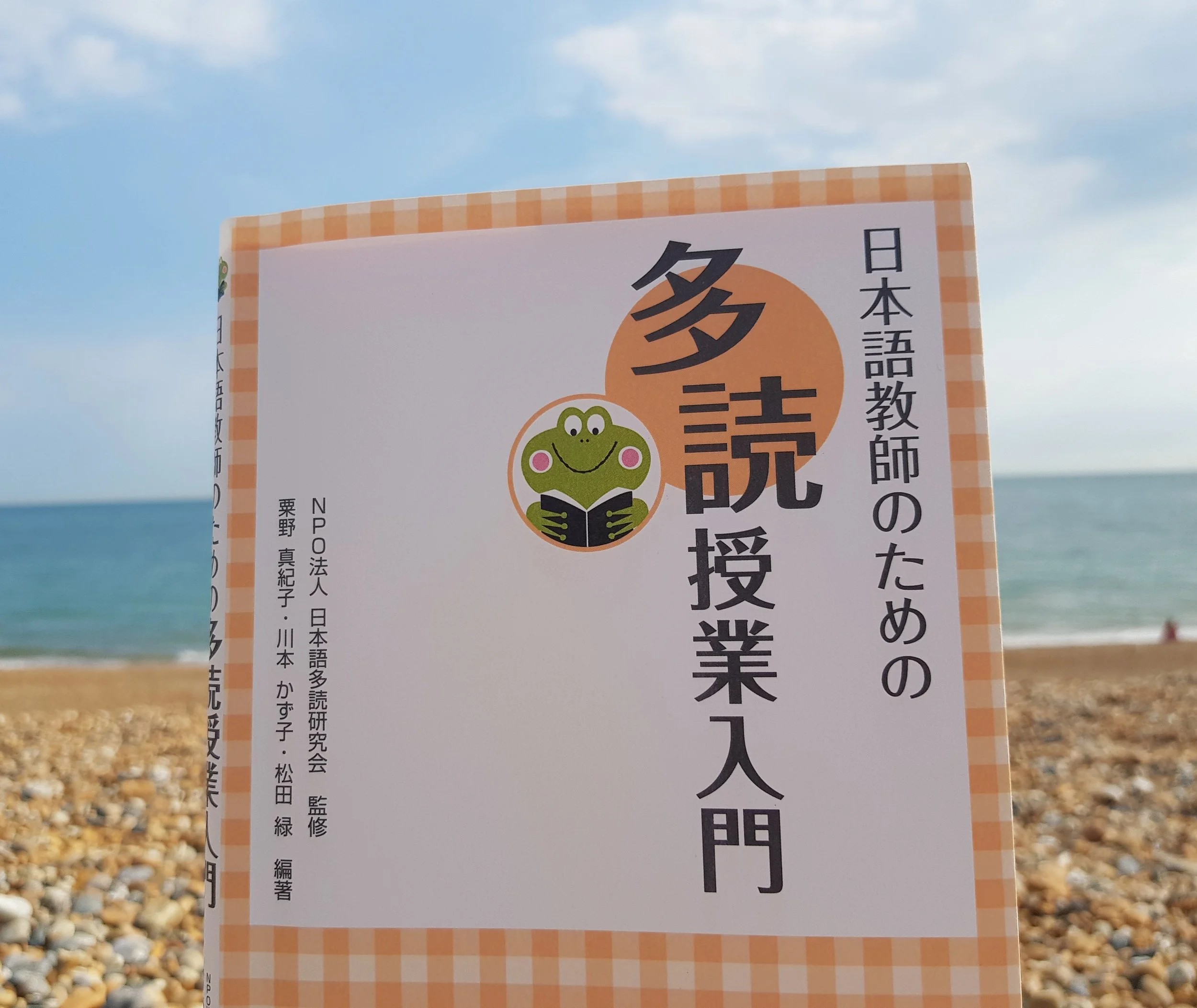

事例紹介や実際的なアドバイスがたくさん入っている「 日本語教師のための多読授業入門」*という本も買って読み始めました。

NPO多言語多読のメンバーからもメールで応援メッセージをもらって、自信が少しつきました。

その後私の新しい多読のコースはブライトンの新聞にも掲載されたんです! それを見て、かなり緊張し始めました。

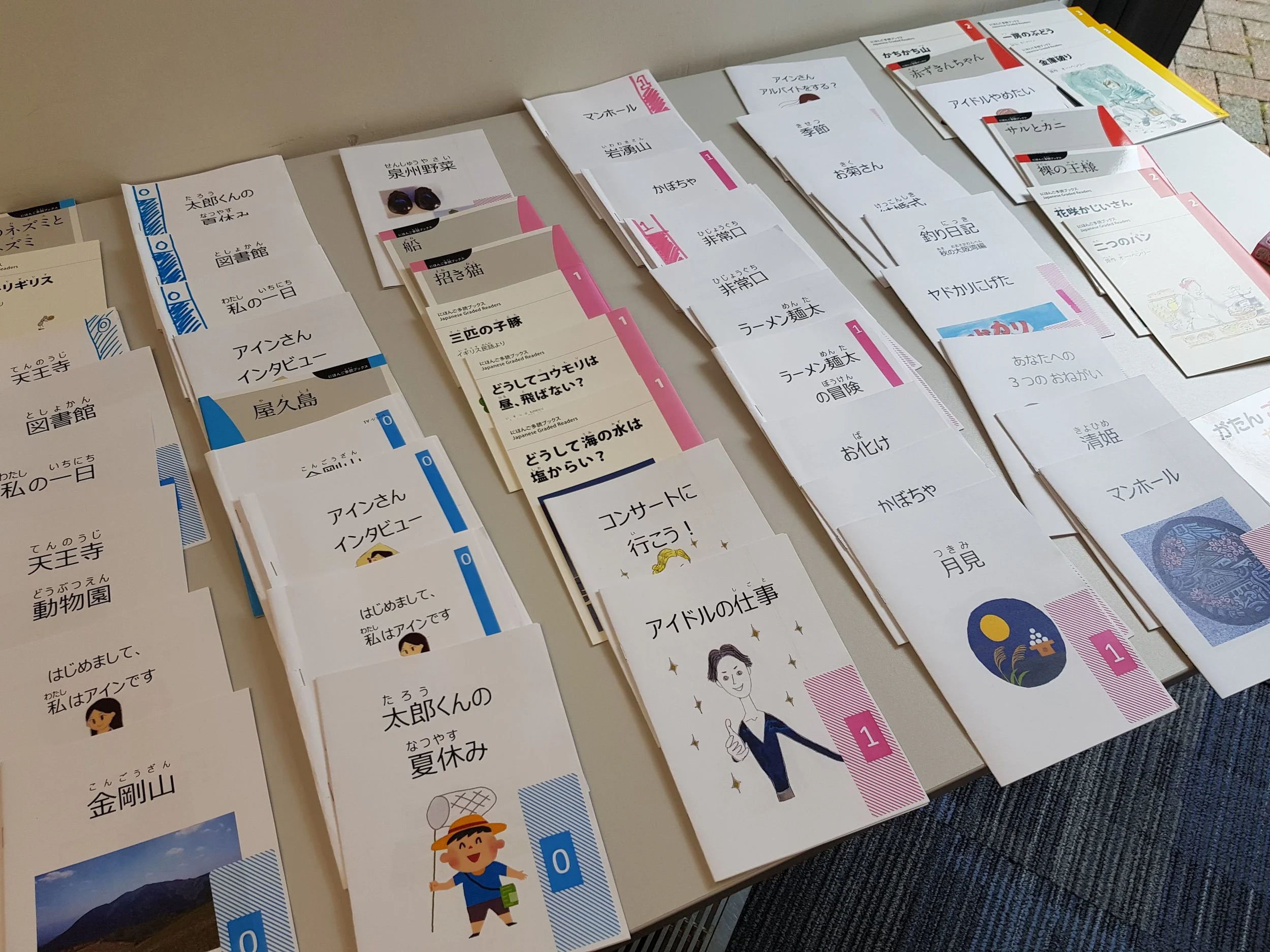

多読の本が日本から届いて、私の生徒には良さそうなレベルだと思いました。でも正直、少しつまらないんじゃないかと心配しました。大人の生徒は本当に「3匹の子ぶた」が読みたいのだろうか?でも、自分で読み始めて、驚きました。すごく楽しかったのです。

絵本だからわからないときは、絵を見て推測してみることもできます。絵を見てもわからないときは、コンテクストから推測するのもいいです。それでもわからなければ、続けて読むだけでいいです。

ただ、辞書を使うことだけは許されていません。(私はこのルールに加えて、知らない単語の意味を先生に聞くのもダメだ、ともうちょっと厳しくしてみました。)

辞書を引いたり言葉の意味を聞いたりするのは、読むことを遮って進むペースが遅くなるんです。そして読むのが楽しくなくなって、生徒はやる気がなくなってしまいます。そこで、多読では知らない単語や表現に出会う時は、飛ばし読みが勧められています。

もう少し先を読めば自然にわかるようになりますから。そして、(これが面白いよ!)時々わからなくて大丈夫です。読めば読むほど、外国語を理解するのが易しくなるんですよ!

私は2007年に日本語を勉強し始めましたが、初めて日本語の本を丸々一冊読み終えたのは2012年でした。あの5年間に多読のことを知っていたらどんなにたくさんの易しい日本語の本が読めていただろう、と今思います。

私の多読のグループに参加した生徒の中には、1年間しか日本語を勉強したことがない人もいましたが、2、3回目のクラスまでに(つまり、2〜3時間の間に)様々な日本語の本も読めたのは、大変な業績だと思います。

レベル別に分かれていて、簡単で、短い本だからこそ、Step Up Japaneseの生徒は早く楽しく読めました。

多読の読み方のルール

(NPO多読のウェブサイトから引用)1.やさしいレベルから読む

絵がついていて、母語に訳さなくても読めるやさしいものから読みましょう。絵をじっくり見て本の世界に入ることが大切です。

2.辞書を引かないで読む

わからない言葉を辞書で調べていると、速く読めません。ゆっくり読むと、つまらなくなってしまいます。わからない言葉が出てきても、辞書を引かないで、絵を見たり、その後の文を読んでみましょう。

3.わからないところは飛ばして読む

絵を見たり、ちょっと考えてもわからない部分は、飛ばしてしまいましょう。楽しく読めていれば、全部わからなくていいのです。

4.進まなくなったら、他の本を読む

進まないのは、読んでいる本が難しいか、興味がないからです。その時は止めて他の本に替えましょう。

生徒がルールを守れるかどうかという心配もありました。辞書を開きたくなったり、興味がないのに無理やり本を読み続けたりすることも絶対あると思いました。みんなにとって和やかな雰囲気が作りたかったけれど、リラックスしすぎた感じだったら、生徒が本を読まずにおしゃべりしてしまう可能性もあるんじゃないか、という不安もありました。

でも、心配することはありませんでした。みんなしっかりルールに従って勉強できました!だって、本をたくさん読むために多読のコースに参加したんですから。

「辞書なし」というのは一番大変だったらしいです。授業の終わりに「ルールに従って多読できた?」と聞いたら、ある生徒は今まで見たこともない漢字一つをこっそり辞書で調べたことを告白しました。その漢字は「臼」でした。

「続けて読んでみたらコンテクストからわかったかもね」と私は言いました。(あと、「臼」はほとんど見かけない漢字なので、調べないで本を読み続けたほうが効率のいい学習法でしょう?とも思いました。)とは言っても、基本的に生徒は辞書を使わずに楽しく読めました。

一回目の授業が終わったら、買った本の数は少なかったと気づきました。生徒がこんなに早く読めると思いませんでした。ネットで多読の本をもっと注文しました。

6週間多読をして、生徒にはいろいろなメリットがあったと私は思います。そして、私も先生としていろいろ学ぶことができました。

これまで授業のために読み物を選ぶとき、私はできるだけ面白そうなものを選ぼうとしてきました。時間があるときは自分で短いストーリーを書いたりもします。でも、多読で読んだ本と比べたら、どれも面白くないなと気づきました。

それはなぜかというと、基本的に教科書に載っている読み物はつまらないからなんです。

簡単な読み物でも面白いものがたくさんあるというのは、多読が私に教えてくれたことなんです。

「ラーメン麺太の冒険」(右)は人気の作品一つでした。

始める前に、生徒はどの本を読めばいいか、自分にとってどのレベルがいいかわからないこともあるんじゃないかと思ったけれど、そういうことは全くありませんでした。生徒は自分が興味のあるトピックで、自分のレベルに合わせた本を選ぶことで、自分の日本語のレベルにも自信がつきました。

授業中、私も簡単な楽しい本を読んで、質問されたときはこんな風にかわしました:

Bさん: 先生、これはどういう意味ですか。

自分: Bさんはどう思いますか。

Bさん: あ、そっか。ルール2ですね。

6週間のコースの真ん中で、私は夏休みの旅行でポルトガルに行ってきました。ビーチでビールを飲みながら「コンビニ人間」という日本語の本を読みました。辞書を開かずに、知らない単語を深く考えずに、早く楽しく読めました。

つまり、「多読」という勉強法は生徒だけではなく、私にも革命的でした。

2007年に知っていたらよかったな、と今思います。あの初めの5年間でどんなにたくさんの易しい日本語の本が読めていただろう!

来年の多読コースについて考えてみたら:

読んだ本について生徒に短い感想を書かせる?:

写真:国際交流基金

音楽を聴きながら読むのはどうかな?

一年で6週間以上した方がいいんじゃない…?

リンク:

NPO多言語多読→ https://tadoku.org/

日本語多読たどくブックス注文申し込み(NPO多言語多読版)→ https://tadoku.org/japanese/to-order

KCよむよむ(無料で多読ブックスをダウンロードできます!)→ https://jfkc.jp/clip/yomyom/

ブライトンの新聞(The Argus)に掲載されたStep Up Japaneseについての記事(英語)! Japanese Language School is Running a New Course in Brighton

→ https://www.theargus.co.uk/news/16361201.japanese-language-school-is-running-a-new-course-in-brighton「日本語教師のための多読授業入門」→ https://amzn.to/2T5AAkY *

「コンビニ人間 → https://amzn.to/2CFJjDA *

*が付いているリンクはアフィリエイトリンクです。そこをクリックして本をご購入いただいた場合は、私はアマゾンからわずかな手数料を受け取ることができます。お客様には普通の価格でご購入いただき、手数料はかかりません。いつも応援してくださってありがとうございます!m(_ _)m

'Tadoku': Here's What I Learned From Running a Japanese Silent Reading Course

I’m not a particularly loud person, but some parts of my Japanese classes are quite loud. We sing and dance, talk and play games. We’ve even been asked to keep the noise down before by a group in the next room who were having a meeting (sorry about that!)

But in summer 2018, I ran a very quiet course. Students worked alone, in a comfortable silence.

And I was the teacher, but I mostly sat reading a hand-stapled book, looking up only to check that students were happily entertaining themselves.

This was Tadoku - a reading class with a difference.

(Click here to read this article in Japanese 日本語版はこちら)

I’m not a particularly loud person, but some parts of my Japanese classes are quite loud. We sing and dance, talk and play games. We’ve even been asked to keep the noise down before by a group in the next room who were having a meeting (sorry about that!)

But in summer 2018, I ran a very quiet course. Students worked alone, in a comfortable silence.

And I was the teacher, but I mostly sat reading a hand-stapled book, looking up only to check that students were happily entertaining themselves.

This was Tadoku - a reading class with a difference.

Tadoku (多読) is a Japanese method of learning foreign languages by reading easy books. Ta (多) means “a lot” and doku (読) is “reading”, so Tadoku literally means “read-a-lot”. It’s sometimes called “extensive reading”.

In Tadoku you read easy material, slightly below your current study level, and in doing so you learn new words, phrases and structures.

I was quite nervous about starting a Tadoku “class”. What would I do in class while students are reading? Just sit there? My students could just read at home, couldn't they? Who’s going to enrol in a silent reading class?

I did some research, and ordered a set of Tadoku graded readers from NPO Tadoku Supporters, a Tokyo-based organisation that promotes the practice of Tadoku around the world.

I also got this book: 日本語教師のための多読授業入門 nihongo kyoushi no tame no tadoku jugyou nyuumon (“An Introduction to Tadoku Instruction for Teachers of Japanese”)*, which had useful case studies and practical advice.

Several members of NPO Tadoku Supporters got in touch from Japan to wish us luck and to offer their support. That was hugely encouraging.

We were in The Argus too (Brighton and Hove’s newspaper)! Now I was starting to get really nervous…

When the Tadoku graded readers arrived, they seemed a good level. But to be honest, I was still a bit concerned that they might be boring. Would my adult students really want to read The Three Little Pigs in Japanese? So I started reading them myself. And to my surprise, it was a lot of fun.

Tadoku readers have pictures, so if you don't understand something you can look at the picture and guess. If you still don’t understand, you can try to guess by context. Or you can just keep reading.

One thing you are not allowed to do in Tadoku is to use your dictionary. I pushed this rule a bit further in our class, to include: you cannot ask your teacher what a word means either!

Using a dictionary (or asking your teacher) slows you down and interrupts your flow. This makes the reading experience less fun, which discourages you. Instead of using the dictionary, in Tadoku you are encouraged to skip over words and phrases you don't know.

If you just keep reading, you may eventually work out what the word means. But – and this is the interesting bit – if you never work it out, that’s fine too. Just keep going, and reading Japanese will get easier.

I started learning Japanese in 2007, but it was 2012 before I read a whole book in Japanese. Imagine how many easy books I could have read in those five years, if only I’d known they existed!

Some of my Tadoku students had only been learning Japanese for a year, and within a few weeks on the course they’d already read several books. I think that’s an amazing achievement.

Of course, these are easy books, level-appropriate and short. That’s why they were able to read them quickly and easily.

The four golden rules of Tadoku (from NPO Tadoku Supporters) are:

Four Golden Rules

1. Start from scratch.

Read easy books you can enjoy without translating. That way, you will understand better and so you will read more.2. Don’t use your dictionary

Don’t use your dictionary when you come across words you don’t know. Guess the meaning from the pictures and/or the story.3. Skip over difficult words, phrases and passages.

If guessing doesn’t work, skip over that word, phrase or passage and go on reading. You can often enjoy the book without understanding every small detail.4. When the going gets tough, quit the book and pick up another.

The going gets tough when the book is not suitable for your level or your interest. Simply throw the book away and start reading something else.

I was a bit nervous that my students wouldn't follow the rules. I thought they would want to use their dictionaries, or would feel compelled to finish books they weren’t interested in. I wanted to create a comfortable, relaxed environment, but I worried that if it was too relaxed, students might sit and chat, rather than read the books.

But of course they followed the rules! They’d signed up for this, after all.

‘No dictionaries’ was probably the hardest part. One student confessed to “cheating “ by looking up an unfamiliar kanji she was encountering for the first time. “If you’d kept going, you might have guessed it from context,” I argued. (Also, 臼 [mortar!] isn’t a particularly common kanji, so arguably looking it up isn’t a great use of time when you could be reading the rest of the book instead).

My students read so fast, after the first session I realise I needed to order more books.

I think my students gained a lot from practicing Tadoku for six weeks. And as their teacher, I learned a lot too.

I realised that a lot of the time, the materials I ask my students to read are not very interesting. I try to pick out the most interesting stories from Japanese textbooks, and when I have time, I sometimes write little stories, to make content relevant or funny (or preferably both!)

But generally speaking, textbook reading exercises are quite boring. Doing Tadoku showed me that easy reading materials can be funny and interesting too.

This story about the prince of ramen (right) was a popular book

I also saw, in a new light, the extent to which my adult students are really good self-guided learners. I thought I might have to help them choose which books to read, or guide them as to which level to pick. No one needed my help with this.

Actually, I just had fun reading easy books and deflecting occasional questions:

Student: “What does this word mean?”

Me: “Hmm…what do you think?”

Student: “Oh yeah…rule 2, sorry”

In the middle of the course, we had a week off and I went to Portugal. I lay on the beach and read a Japanese book (コンビニ人間 kombini ningen, Convenience Store Woman) without using my dictionary. I raced through it, enjoying the book for what it is.

So Tadoku was pretty revolutionary for me, too, as well as my students.

I wish I’d known about Tadoku in 2007…I could have read some fun books in those first five years!

Thoughts for next year:

Students could write short book reviews in the back of each book? Like this:

Photo: Japan Foundation

Could we listen to music while reading?

Maybe we should do Tadoku for more than six weeks of the year…?

Links:

Links with an asterisk* are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

NPO Tadoku Supporters (English page) → https://tadoku.org/en/vision

Buy Tadoku Books online (English/Japanese page) → https://tadoku.org/japanese/to-order

KC Clip - download free Tadoku books (Japanese page) → http://jfkc.jp/clip/yomyom/index.html

Step Up Japanese in The Argus! Japanese Language School is Running a New Course in Brighton (English)→ https://www.theargus.co.uk/news/16361201.japanese-language-school-is-running-a-new-course-in-brighton

日本語教師のための多読授業入門 An Introduction to Tadoku Instruction for Teachers of Japanese (Japanese book) → https://amzn.to/2T5AAkY*

コンビニ人間 Convenience Store Woman (Japanese book)→ https://amzn.to/2CFJjDA*

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.