Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Why Does The Japanese Language Have So Many Alphabets?

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

Until the 1st or 2nd century, Japan had no writing system. Then, sometime before 500AD, kanji - Chinese characters - made its way to Japan from China (probably via Korea).

These characters were originally used for their meaning only - they weren't used to write native Japanese words.

↓ And at that time, Japanese writing looked like this. Look, it looks like Chinese!

(Image Source - Nihon Shoki, Wikipedia)

But it was inconvenient not being able to write native Japanese words down, and so people began to use kanji to represent the phonetic sounds of Japanese words, not only the meaning. This is called manyougana and is the oldest native Japanese writing system.

For example, in manyougana the word asa (morning) was written 安佐 (that's a kanji for the “a” sound - 安 - and another for the “sa” sound - 佐). These characters indicate the sound of the word - “asa” - but not its meaning.

In modern Japanese we'd use 朝, the kanji that means "morning" for asa. This character shows its meaning AND its sound.

The problem was, manyougana used multiple kanji for each phonetic sound - over 900 characters for the 90 phonetic sounds in Japanese - so it was inefficient and time-consuming.

Gradually, people began to simplify kanji characters into simpler characters - that's where hiragana and katakana came from.

Katakana means "broken kana" or "fragmented characters". It was developed by monks in the 9th century who were annotating Chinese texts so that Japanese people could read them. So katakana was really an early form of shorthand.

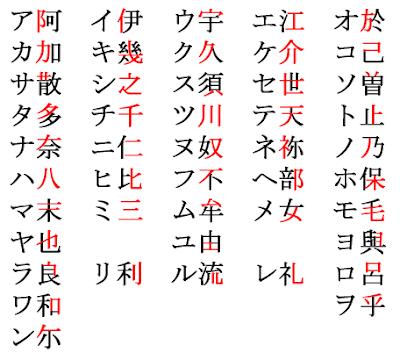

Each katakana character comes from part of a kanji: for example, the top half of the kanji 呂 became katakana ロ (ro), and the left side of the kanji 加 became katakana カ (ka).

↓ Each katakana comes from part of a kanji.

(Source - Katakana origins, Wikipedia)

Women in Japan, on the other hand, wrote in cursive script, which was gradually simplified into hiragana. That's why hiragana looks all loopy and squiggly. Like katakana, hiragana characters don't have meaning - they just indicate sound.

↓ How kanji (top) evolved into manyougana (middle in red), and then hiragana (bottom).

(Source - Hiragana evolution, Wikipedia)

Because it was simpler than kanji, hiragana was accessible for women who didn't have the same education level as men. The 11th-century classic The Tale of Genji was written almost entirely in hiragana, because it was written by a female author for a female audience.

Modern Japanese writing uses all three of these “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji - often all mixed up in the same sentence.

What would 12th-century people in Japan think of my students, 900 years later, learning hiragana as they take their first steps into the Japanese language?

First published 28th Oct 2016

Updated 27th Jan 2020

How Do I Know if a Group Language Class is For Me?

If you’re thinking about taking Japanese lessons, one of the first things you’ll have to decide is whether you want to join a group class, or take one-to-one lessons.

There are pros and cons to all methods of learning a language. Here, I’ll look at some of the key advantages of joining a group.

If you’re thinking about taking Japanese lessons, one of the first things you’ll have to decide is whether you want to join a group class, or take one-to-one lessons.

There are pros and cons to all methods of learning a language. Here, I’ll look at some of the key advantages of joining a group.

1) Meet other language learners

Classes give you access to a teacher, but a group class also provide you with an instant group of other people with the same interest as you.

You can speak in your target language together, go out for dinner and order in Japanese, and message each other asking "what was last week's homework again?"

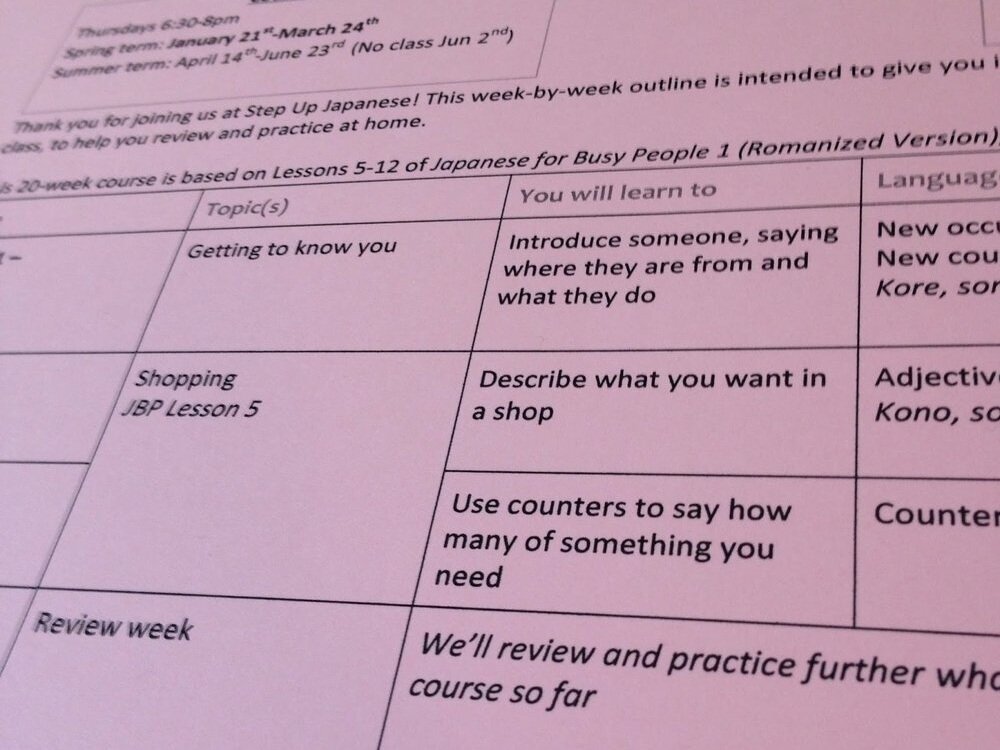

(Just kidding - thanks to the course outline I'll provide you with, you'll always know what this week's homework is.)

In a group class, students can support and help each other. It's obvious to me that my lovely students gain a lot from each others' support!

2) Keep a regular schedule

To gain any skill, you need to practice regularly. The great thing about having class on a regular day is it forces you to practice. Unlike exclusive self-study where you'll always have an excuse to procrastinate, weekly classes require you to be prepared for every class so you can get the most out of it.

Practice makes perfect, after all.

3) It's your class

You might feel like the only way to get a class tailored to your needs is to take one-to-one lessons. But a good group class - especially one for a small group of students - should be tailored to the students in it as much as a private lesson would be.

That's why I ask my students to give me regular feedback (informally, and through anonymous questionnaires) about how class is going and where you want it to go next.

It's your class, not mine, and we can focus on what you want to focus on.

That doesn't mean I'm going to do the hard work for you. If you want to get good at Japanese, you'll need to find ways of practicing and exposing yourself to the language as much as possible outside of class too.

But a group class can provide the basis of your knowledge, a structure to work with, and a group of friendly faces to answer your questions.

It also gives you a great excuse to go to that great Japanese restaurant again with your classmates.

First published June 2016; updated 9th January 2020.

What to Write in Japanese New Year's Cards

Every year, Japanese households send and receive New Year’s postcards called nengajō (年賀状). The cards are sent to friends and family, as well as to people you have work connections with.

If you post your cards in Japan before the cut-off date in late December, the postal service guarantees to deliver them on January 1st.

Every year, Japanese households send and receive New Year’s postcards called nengajō (年賀状). The cards are sent to friends and family, as well as to people you have work connections with.

Image: yubin-nenga.jp

If you post your cards in Japan before the cut-off date in late December, the postal service guarantees to deliver them on January 1st.

Card designs often feature the Chinese zodiac animal of the new year. For example, 2016 was the year of the monkey, so lots of designs that year included monkeys!

Cards sold in shops or at the post office usually have a lottery number on the bottom, too:

Nengajō greetings are a good opportunity to practice your Japanese handwriting. You might want to practice on a piece of blank paper before writing on the card itself.

Every year, we use printed templates to write New Year messages in class. I love helping my students write nengajō to their family and friends.

Photo by Bob Prosser

But what should you write in nengajō?

There are two key phrases to remember for writing nengajō:

1. あけましておめでとうございます!

akemashite omedetou gozaimasu

Happy New Year!

2. 今年もよろしくお願いします。

kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu

I hope for your favour again in the coming year.

You could also go for something like:

明るく楽しい一年でありますように

Akaruku tanoshii ichinen de arimasu you ni

I hope you have a wonderful year.

or:

旧年中は大変お世話になりました。

Kyuunenjuu wa taihen osewa ni narimashita.

Thank you for your kindness throughout the last year.

Photo by Bob Prosser

Photo by Bob Prosser

A very happy new year from me (Fran), and:

今年もよろしくお願いします!

Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu!

(I hope for your favour again in the coming year)

First published 31st December 2018

Updated 16th December 2019

Is it Shinbun or Shimbun?

It’s both. And it’s neither.

Beginner students often ask whether “shinbun” or “shimbun” (the word for “newspaper” in Japanese) is correct.

You’ll see both spellings...and books about the Japanese language don’t seem to be able to agree either.

If you look at the two most popular Japanese beginner textbooks, Genki has “shinbun”, whereas Japanese for Busy People has “shimbun” and also “kombanwa”.

But why?

It’s both. And it’s neither.

Beginner students often ask whether “shinbun” or “shimbun” is the correct spelling of the word for “newspaper” in Japanese.

You’ll see both spellings… and books about the Japanese language don’t seem to be able to agree either.

If you look at the two most popular Japanese beginner textbooks, Genki has “shinbun”, whereas Japanese for Busy People has “shimbun” and also “kombanwa”.

But why?

Well, there are different ways of writing Japanese in romaji (roman letters i.e. the alphabet). All romaji is an approximation, and there are two different major systems, both used widely.

In elementary school, Japanese kids learn Kunrei, the government’s official romanization system. Kunrei is more consistent, but not particularly intuitive for non-Japanese speakers.

In the Kunrei system:

しょ is written as “syo”

こうこう is written as “kookoo”

But textbooks for people learning Japanese tend to use the Hepburn system, which is easier for non-native speakers. Modernised Hepburn writes しょ as “sho” and こうこう as “kōkō”.

"N or M?"

Under the older Hepburn system of romaji, a ん (n) before a "b" or "p" sound used to be written as m. This gave us romaji spellings like shimbun and sempai. (The Kunrei system, on the other hand, never used this rogue "m" at all).

When Modernised Hepburn was introduced in 1954, the "m" rule was dropped. Since 1954, both major systems have said that these words should be written as shinbun and senpai.

So shimbun-with-an-m hasn't been officially used since 1954...but it is still the preferred romanization of several major Japanese newspapers: Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun.

So it seems like shimbun-with-an-m is still with us.

"So which is better?"

Arguably, “shimbun” is closer to the pronunciation of the word. There IS a sound change going on here – before a “p” or “b” sound in Japanese, the ん sounds more like “m” than “n”.

But "shinbun" is more consistent, and personally I prefer it - especially if you’re still learning kana.

There is no ‘m’ hiragana, and I don’t want you wasting your time looking for it on your kana chart.

"Which is more common?"

I don’t know. But it kind of doesn’t matter which one is more common: the Japanese way to write the word for newspaper isn't “shinbun” or “shimbun”. It’s not really even しんぶん. The Japanese word for newspaper is 新聞.

Which brings me neatly onto my next question...

“Why are you writing it in romaji anyway?"

Some people say that the shimbun/shinbun thing is a slightly pointless question. Everyone should just learn the kana, and then we wouldn't have this problem, right?

But romaji isn’t just read by people learning Japanese. Romanised stations and place names and even people's names are read by millions of people visiting Japan who don’t know Japanese.

And for people who don’t speak Japanese (especially English speakers), it's easier to guess the pronunciation of “shokuji” than “syokuzi”.

So, while the current system is a bit of a muddle, it's the best thing we've got. I think we can all agree on that.

(First published February 12, 2016. Updated June 21, 2019)