Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

Hiking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage Trail in 2018 - A Round-Up

The week I spent last spring walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail was peaceful, thought-provoking, and challenging - often all at once.

Here’s all my writing about that trip in one place.

The week I spent last spring walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage trail was peaceful, thought-provoking, and challenging - often all at once.

Here’s all my writing about that trip in one place.

Part 1 - Plan, plan, plan!

Are you a planner? Or a no-planner?

Some people like to "wing it" when they travel. They book a ticket and turn up, deciding what to do once they arrive. Me, I like to have things planned out. Especially when the trip involves a week of solo walking in Japan…

Click here to read Part 1 - Plan, plan, plan!

Part 2 - The Best First Day in Japan

Spoiler alert: this post isn't about the Shikoku pilgrimage, although it is about the same trip. It's about what I did with my spare first day in Nagoya: the lost day...

Arriving first thing in the morning on a long-haul flight is not ideal. You're tired, jet-lagged and yet you need to stay awake until a normal bedtime, so you can adjust your body clock.

I had almost 12 hours to kill on that first day, and was waiting for my friends to finish work.

So what do you do with a whole day to yourself?

Ciick here to read Part 2 - The Best First Day in Japan

Part 3 - What To Wear

When I told my Japanese friends I was planning to walk the Shikoku Henro trail, several of them said the same thing. "Are you going to wear a hat?"

For many people, the image of a walker in a bamboo hat is the first thing that comes to mind when they think of the pilgrimage.

But what "should" you wear on the Shikoku 88, a Buddhist pilgrimage trail?

Click here to read Part 3 - What To Wear

Part 4 - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

A stranger, they say, is just a friend you haven't met yet.

And talking to strangers is a great way to speak lots of Japanese. I did lots of this while walking the first section of the Shikoku pilgrimage this spring.

But how do you start a conversation with a stranger? Here are some ideas to get you going, even if you're a beginner at Japanese.

Click here to read Part 4 - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Part 5 - Signs of Shikoku

I heard lots of "gambatte kudasai" (“keep going!”) walking the first leg of the Shikoku 88 pilgrimage this spring. It was written everywhere too - in fact there were lots of interesting signs.

The pilgrimage trail is pretty well marked. Signage is consistently spaced, and in many places there's a way-marker every 100 metres.

But it's also endearingly inconsistent in design - on some stretches every sign is different, and many are handmade….

Click here to read Part 5 - Signs of Shikoku

Part 6 - Shouting at the French

"Sumimaseeeeeeeeeeeeeeen!" I shouted. ("Excuse me!")

The couple turned round, but they didn't move.

They were both dressed in full pilgrim garb: long white clothes, their heads protected by conical hats.

"Otoshimono desu!" ("You dropped this!")

They stared at me blankly. I waved the little grey bag with its digital camera inside. "KAMERA!"

I still couldn't make out their faces, but I thought I saw a glimmer of recognition. One of the pair walked towards me, and it was only then that I saw her face.

"I thought you were Japanese," she said, and I heard a European accent I couldn't place.

"I thought you were Japanese," I said…

Click here to read Part 6 - Shouting at the French

Part 7 - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

Kyūkei shimashou" (休憩しましょう) is one of the first phrases I teach all my students, and it means "let's take a break".

Rest is every bit as important as activity - perhaps more important. In class, it helps you digest and absorb ideas.

And on a long-distance walk, rest stops (called kyūkeijo 休憩所 in Japanese) can be a good place to

strike up a conversation.

Click here to read Part 7 - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

Part 8 - O-settai, or, "I'll treasure this tissue case"

Near Kumadani-ji, temple number 8, we had stopped in front of some glorious cherry blossom, and I got chatting to two older gentlemen who were walking the trail. One told me he had never spoken to a gaijin-san, foreigner, before. We took some pictures in front of the cherry blossom, and walked up the hill together.

Further up the road, a lady came out of her house and gave us some hard-boiled sweets.

The sweets were a form of o-settai, small gifts given to walking pilgrims. Traditionally, pilgrims didn't carry money, so they were helped along their way by gifts of food, lodging and other acts of generosity from local people.

“Wait here,” she said when she saw me, “I have something else for you.”

Click here to read Part 8 - O-settai, or, "I'll treasure this tissue case"

Part 9 - Eating Shōjin Ryōri - Buddhist temple food

The “strange” meals were “quite unlike any food I’ve ever tasted”, wrote one visitor to the Sekishoin Shukubo temple in Mount Kōya, eliciting the blunt reply from one monk:

“Yeah, it’s Japanese monastic cuisine you uneducated fuck.”

Guests online also complained about the lack of heating in the Buddhist temple, the absence of English tour guides, and “basic and vegetarian” food.

I stayed in a couple of shukubo (宿坊) earlier this year…

Click here to read Part 9 - Eating Shōjin Ryōri - Buddhist temple food

Thanks so much for reading! I hope you found it useful and/or interesting.

I can’t wait to go back and walk the next bit…

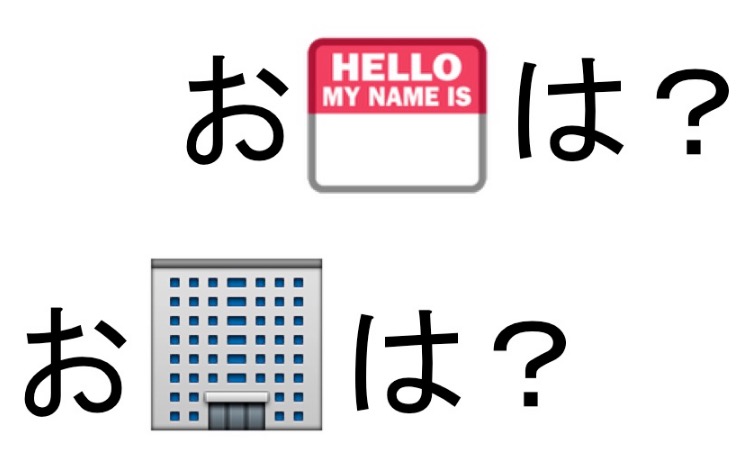

Three Ways You Should Be Using The Japanese Honorific お (Part 1)

Fairly early on in your Japanese-learning journey, you'll learn some set phrases like:

o-genki desu ka? (How are you?)

o-shigoto wa nan desu ka? (What's your job?)

Usually I teach that the “o” in o-genki desu ka makes the question more polite. This is true, but it’s not the whole story.

Fairly early on in your Japanese-learning journey, you'll learn some set phrases like:

o-genki desu ka? (How are you?)

o-shigoto wa nan desu ka? (What's your job?)

Usually I teach that the “o” in o-genki desu ka makes the question more polite. This is true, but it’s not the whole story.

Honorific o (or sometimes go) is basically used for three things:

1) Being polite about someone else

It's good to be more polite about other people than you are about yourself, right?

So when you're speaking about someone else, there are certain words that get an o (or go) on the front:

o-shigoto お仕事 (your honourable job)

o-sumai お住まい (your respected abode)

Like in these common Japanese questions:

o-namae wa? お名前は? (What is your esteemed name?)

o-genki desu ka お元気ですか。 (Are you [person I respect] well?)

When you talk about yourself, however, don't use o or go: just namae, genki, kazoku, shigoto. You can't talk about your own o-namae or go-kazoku!

2) Sounding more polite generally

Adding o to a word can make your speech sound more polished. Words that don’t necessarily need o, but often get it, include:

sushi / o-sushi (sushi)

kome / o-kome (rice)

sake / o-sake (rice wine)

With these words, either way is fine. If you're trying to speak politely you might want to use the 'o' version.

Unlike the first group, this kind of o isn’t anything to do with whose sushi or sake it is. It just sounds a bit nicer if you stick the o on there. Like you’re respecting the rice.

3) Some words just always have it

So, some words need o/go only when you're talking about someone else. Others can either have it or not.

There's a third category, too - words where the o/go has been subsumed into the word completely, and can't really be detached:

Gohan (ご飯, meal/cooked rice) always needs go - there's no unadorned word "han" for rice (although there presumably was at some point.)

O-cha (お茶, tea) pretty much always gets o, as does o-kane (お金, money). Just cha or kane sounds quite rough.

Words like this don't really belong to the "o/go is polite" rule of thumb. It's best just to learn them as whole words.

O or go?

Generally, words of Chinese origin take the prefix go, instead of o:

go-kazoku (your esteemed family)

go-kyouryoku (your noble cooperation)

go-ryoushin (your respected parents)

There are some exceptions, though… but more on that next time.

First published (as “Hey! What’s That お Doing There?”) in December 2015

Updated 21 December, 2018

Why Don't Japanese Questions Have Question Marks?

Often, questions written in Japanese end in a full stop, not a question mark. But why?

Often, questions written in Japanese end in a full stop, not a question mark. But why?

When not to use a question mark

If a question ends in the question marker ka (か), it doesn't need a question mark, because the 'ka' tells us that this is a question:

今何時ですか。

Ima nanji desu ka.

What time is it?

That doesn't mean you can't use a question mark with か. People do it, especially in casual contexts. You just don't need to (and you shouldn't in formal writing).

Here's a question with か and a question mark, from the McDonald’s Japan website:

ハンバーガーは長い間放置しても腐らないと聞きました。本当ですか?

Hambaagaa wa nagai aida houchi shitemo kusaranai to kikimashita. Hontou desu ka?

I heard you can leave a hamburger for a long time and it won't go bad. Is that true?

Adding a question mark after か here makes 本当ですか? sound a bit more casual, friendly and questioning.

When to use a question mark

In questions without ka, question marks are pretty common:

明日は?

Ashita wa?

How about tomorrow?

お仕事は?

O-shigoto wa?

What's your job?

学校に行った?

Gakkou ni itta?

You went to school?

Without a question mark, these short written statements wouldn't obviously be questions.

That's all from me for today. So... any questions?

First published December 11, 2015

Updated December 13, 2018

Are Loanwords "Real" Japanese?

Shortly after I started studying Japanese at university, I got an email from a friend in Sweden:

“How’s it going? Learned any more ‘Japanese words’ like camera and video?”

I’d copy-pasted her some of the "new words" from my textbook. There was a list of them - words like kamera (camera) and rajio (radio)…

I felt like I was cheating. These aren’t Japanese words!

Or are they?

Shortly after I started studying Japanese at university, I got an email from a friend in Sweden:

“How’s it going? Learned any more ‘Japanese words’ like camera and video?”

I’d copy-pasted her some of the "new words" from my textbook. There was a list of them - words like kamera (camera) and rajio (radio)…

I felt like I was cheating. These aren’t Japanese words!

Or are they?

Japanese has LOADS of these loanwords - words borrowed from other languages. And two things often happen when a foreign word gets used as a loanword:

Extra vowel sounds

All Japanese syllables - except ん (n) - end in a vowel sound. That means when we convert a foreign word into Japanese, some rogue vowels get thrown in there too:

hot dogホットドッグ hotto doggu

world cup ワールドカップ waarudo kappu

2. Abbreviations

Adding in all those extra vowels makes these loanwords in Japanese much longer than their English equivalents, so they often get shortened:

suupaamaaketto スーパーマーケット

↓

suupaa スーパー (supermarket)

depaatomento sutoa デパートメントストア

↓

depaato デパート (department store)

↓ Spot the katakana loanword(s)!

Sometimes the first bit of both words gets used:

dejitaru kamera デジタルカメラ

↓

dejikame デジカメ (digital camera)

paasonaru konpuuta パーソナルコンピュータ

↓

pasokon パソコン (personal computer)

...which I hope you'll agree are some of the most adorable words ever.

These loanwords, therefore, can teach us a bit about Japanese pronunciation, as well as the Japanese love of abbreviations. I was wrong about them not being "Japanese words", though - depaato and pasokon are definitely Japanese words. Japan may have borrowed them, but it's not giving them back.

Is learning loanwords cheating? What's your favourite Japanese loanword? Let me know in the comments!

First published December 2015

Updated December 7, 2018

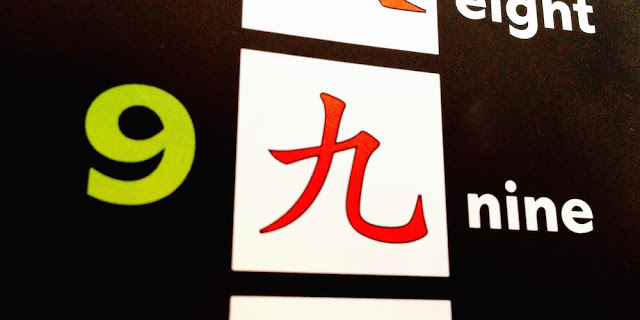

Is it Nana or Shichi? A Brief Introduction to Japanese Numbers

Counting 1-10 should be easy, right?

“Ichi, ni, san, yon... (or is it shi?), go, roku, nana (or shichi), hachi, kyuu (but sometimes ku)...”

Oh, yeah...Japanese has multiple words for the same number! Seven can be either "nana" or "shichi", for example.

So how do you know which word to use?

Sometimes, either is fine – like when you count 1-10, for example. But sometimes, only one word will do.

Let's take a look at some of those special cases.

Counting 1-10 should be easy, right?

“Ichi, ni, san, yon... (or is it shi?), go, roku, nana (or shichi), hachi, kyuu (but sometimes ku)...”

Oh, yeah...Japanese has multiple words for the same number! Seven can be either "nana" or "shichi", for example.

So how do you know which word to use?

Sometimes, either is fine – like when you count 1-10, for example. But sometimes, only one word will do.

Let's take a look at some of those special cases.

FOUR - yon / shi / yo

Yon is used in ages:

よんさい yonsai four years old

and in big numbers:

よんじゅう yonjuu 40

よんひゃく yonhyaku 400

よんせん yonsen 4,000

よんまん yonman 40,000

But you have to use shi for the month:

しがつ shigatsu April

And there’s yo, too, occasionally. Think of it as an abbreviated "yon":

よじ yoji 4 o’clock

よにん yo’nin four people

SEVEN - nana / shichi

Nana is also used in ages:

ななさい nanasai 7 years old

...and in big numbers:

ななじゅう nanajuu 70

ななひゃく nanahyaku 700

ななせん nanasen 7,000

ななまん nanaman 70,000

But shichi must be used in the month AND the o’clock:

しちがつ shichigatsu July

しちじ shichiji 7 o’clock

NINE - kyuu / ku

Nine is usually kyuu, but a notable exception is:

9時くじ kuji nine o’clock

When is a one not a one? When it’s January

So why does Japanese have multiple words for the same number?

It's partly to do with superstition - “shi” sounds like the Japanese word for death and “ku” can mean suffering; “shichi” can also mean “place of death”.

But actually, most languages have multiple words for numbers. We have this in English, too:

1st is “first” (not “one-th”)

The first month of the year is “January” (not “month one”)

Practice makes perfect

Once you've learned which number word to use when, the next step is to practise until they stick!

Anyway, I hope these examples have demystified Japanese numbers for you a little bit. How do you like to practise numbers?

This blog post started life as the answer to a question in one of my Japanese classes (back in 2015!) If you have a question you can't find the answer to, please let me know in the comments or on Facebook / Twitter.

First published November 2015

Updated 27th January, 2019

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 9) - Eating Shōjin Ryōri - Buddhist temple food

The “strange” meals were “quite unlike any food I’ve ever tasted”, wrote one visitor to the Sekishoin Shukubo temple in Mount Kōya, eliciting the blunt reply from one monk:

“Yeah, it’s Japanese monastic cuisine you uneducated fuck.”

Guests online also complained about…

The “strange” meals were “quite unlike any food I’ve ever tasted”, wrote one visitor to the Sekishoin Shukubo temple in Mount Kōya, eliciting the blunt reply from one monk:

“Yeah, it’s Japanese monastic cuisine you uneducated fuck.”

Guests online also complained about the lack of heating in the Buddhist temple, the absence of English tour guides, and “basic and vegetarian” food. In an interview with the Guardian, Buddhist monk Daniel Kimura promised to “tone down” his comments in future and said he regretted swearing in his responses.

I stayed in a couple of shukubo (宿坊) earlier this year. Shukubo are temple lodgings for pilgrims, usually simple and plain by design. And yes, the food served is usually vegetarian - often it’s shojin ryori (精進料理), Buddhist temple food prepared to strict and fascinating guidelines. Shojin ryori probably is unlike anything the visitor had ever had before.

Breakfast at shousanji (焼山寺), temple number 12.

A key principle of shojin ryori, which literally means “devotional cuisine”, is that it is prepared without any animal products. This is grounded in the Buddhist principle of ahimsa, compassion for all living things. Traditionally, shojin ryori doesn't use eggs or dairy either, meaning it’s often vegan.

When you consider that truly vegetarian food is not that easy to find in Japan, where many meals contain dashi fish stock, the fact that many temples serve vegan food is pretty interesting.

Shojin ryori also follows the “rule of five”: every meal must offer five colours (green, yellow, red, black, and white) as well as five flavours (sweet, spicy, sour, bitter, and salty). This guarantees a wide variety different vegetable-based ingredients. And seasonal vegetables are used – so it’s fresh, as well as healthy.

Garlic, onions and other pungent flavours are prohibited in shojin ryori. Instead of fish stock, seaweed or vegetable stock is used. This gives it a really delicate flavour, I think. Protein tends to come in the form of beans and tofu.

I stayed in three temples on my spring trip to Shikoku. I’m not vegetarian now, but I was for over ten years, and I love vegetarian food. And I loved shojin ryori.

Dinner at shousan-ji (焼山寺). Can you spot the five colours (green, yellow, red, black, and white)?

dinner in the dining hall at juraku-ji (十楽寺), temple number 7. Some people abstain from alcohol while on the pilgrimage, but in this temple you could get beer or sake with dinner.

Breakfast at tatsue-ji (立江寺), temple 19. i ate with a nice dutch couple who were touring japan for the first time. they loved everything except the ‘terrible coffee’!

the food at tatsue-ji was meat-free, but with some fish ingredients.

The rest of the time I stayed in minshuku (民宿 guest houses). In the minshuku, meals usually have meat or fish.

If you have the chance to stay in a shukubo, I really, really recommend it. Just don’t complain about the food being vegetarian or the corridors being unheated!

Related posts:

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 1) - Plan, plan, plan!

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 2) - The Best First Day in Japan

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 3) - What To Wear

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage(Part 4) - How to Talk to Strangers in Japanese

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 5) - Signs of Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 6) - Shouting at the French

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 7) - Five Types of Rest Stop You'll Find Hiking In Shikoku

Walking the Shikoku 88 Pilgrimage (Part 8) - O-settai, or, "I'll Treasure This Tissue Case"

How to Use Anki to Not Forget Vocabulary

Lots of you probably use flashcards already. Why not use really, really clever ones?

Imagine you're studying Japanese vocabulary with a set of flashcards. You go through the cards one by one, putting them into a "pass" pile if you remembered them, and a "fail" pile if you didn't.

When you finish, you work through the "fail" pile again. You get about half of them right.

The next day, you go through all the cards again. It takes ages, and it's boring - you did all these yesterday…

You want to use flashcards. Why not use really, really clever ones?

Imagine you're studying Japanese vocabulary with a set of paper flashcards. You go through the cards one by one, putting them into a "pass" pile if you remembered them, and a "fail" pile if you didn't.

When you finish, you work through the "fail" pile again. You get about half of them right.

The next day, you go through all the cards again. It takes ages, and it's boring - you did all these yesterday.

Or maybe you start with the "fail" pile. But this card pile is smaller, so when the cards come up, you just remember the fact that you failed them yesterday!

This approach is okay, if you’re enjoying yourself. (Anything is okay, as long as you're having fun. This is my basic approach to language learning).

But you can make flashcards much more efficient - and stop wasting your time - with a spaced repetition system like Anki.

The power of active recall

When you use flashcards to test yourself, you're engaging in active recall - you're pushing your brain to remember something. This is the most effective way to commit things to memory.

You know that feeling when you're struggling to remember a word, and then finally get to it? That's active recall.

At that moment, you've just cemented the correct meaning of the word in your mind. And you'll remember it much quicker next time.

What is Anki?

Anki is a spaced repetition system (SRS) - a system for remembering things. It's free for PC / Mac, and Android. The iPhone app is not free (it’s £23.99), so I'd try it out on a computer first and see if you like it.

(Then again, it might be the best £23.99 you ever spend...)

Anki shows you digital flashcards and tests you. It then spaces out the cards into the future, depending on how difficult you found them.

If you don't remember a word, Anki shows you it again in 10 minutes.

If you said it's easy, it might show you in three days. If in three days it's still easy, it waits seven days before it tests you on that word again.

If you keep getting it right, the interval increases exponentially, until Anki knows it'll be years before you forget that word. When you get it wrong, Anki knows you need to practice that word again soon.

So Anki sorts the “piles” of flashcards for you, testing you on material just as it thinks you're about to forget it.

I told you it was clever.

What to study?

Anki has shared decks that you can download - sets of flashcards made by other users.

If you're studying for the JLPT, there are loads of decks for that. And whatever Japanese textbook you're using, there'll be an Anki deck for it.

You probably don’t want to memorise every word in your textbook - maybe you don't think you need the word for "municipal hospital", or you want to focus on certain areas. Just delete the cards you don't need.

Or you can make your own decks by adding your own material. That's probably the best approach.

Maybe you want to memorise verb conjugations (masu form to -te form; -nai form, etc). Or maybe you just can't remember the difference between ウ and ワ. Stick it in your Anki deck, and forget about forgetting things.

What not to study

A word of caution - don't try and memorise things you don't understand yet.

For example, let's say in your textbook there's a chart giving the -nai forms of common verbs. You could put those in your anki deck and memorise them, I guess.

But it's no use if you don't know what the -nai form is and how it's used. Learn what it is - practice it, speak it, own it - and use spaced repetition to help you remember.

A useful companion

I tried to use Anki to re-learn some French last year (my high school French class was a long time ago).

I downloaded a beginner French deck, and I'd sit on the train testing myself on vocabulary. It helped a bit, but I didn't magically learn to speak French! That's basically because I never tried to produce any French in that time. I didn't speak with anyone or write down anything in French...

To master a language, you need to speak out loud, and listen a lot.Spaced repetition is a brilliant tool and a companion to learning. But it's not everything... you need to actually practice too.

I'd love to know how you're getting on with Anki. Do you love it or hate it? Tweet me a screenshot of your cards, or let me know in the comments.

First published May 08, 2017

Updated October 09, 2018

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.