Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

What is Shadowing and Can it Improve Your Spoken Japanese? I Tried Shadowing Every Day for a Month

“I can read it and understand it, but I can’t speak like that!”

…Does this sound familiar?

Almost all language learners feel that their production (speaking and writing) is not as strong as their comprehension (listening and reading). This is normal, but it’s still frustrating.

One method that is supposed to improve your listening and speaking is shadowing.

I’d heard of shadowing before, and I’d seen Japanese language learning resources devoted to it – but I’ve never tried it. I decided to try this every day for a month, and see what impact it had.

“I can read it and understand it, but I can’t speak like that!”

…Does this sound familiar?

Almost all language learners feel that their production (speaking and writing) is not as strong as their comprehension (listening and reading). This is normal, but it can be very frustrating.

One method that is supposed to improve your listening and speaking is shadowing.

I’m a Japanese teacher, but as a non-native speaker, I’m a Japanese learner too. I’m confident with my spoken Japanese, but like everybody I stumble over my words sometimes. And I’m aware that my spoken Japanese will never feel quite the same as my native language does.

Earlier in the year, while trying to speak Japanese every day for a month (without being in Japan), I went on a deep dive into Japanese pitch accent.

(Pitch accent In brief: Japanese has high-low tones, and pronouncing a word with the wrong pitch accent pattern makes you sound unnatural.)

I started watching the fantastic “Japanese Phonetics by Dogen” series on YouTube. Dogen recommends two key ideas to improve your spoken Japanese:

1) Record yourself and listen back to the recording, checking for speech errors

2) Practise shadowing every day

I’d heard of shadowing before, and I’d seen Japanese language learning resources devoted to it – but I’ve never tried it. I decided to try this every day in March, and see what impact it had.

I was hoping to improve my phonetic awareness (like most non-native speakers, I had never explicitly learned Japanese pitch accent before this). I also hoped that shadowing practice would work a bit like warm-up exercises to speaking, allowing me to speak more quickly without losing accuracy.

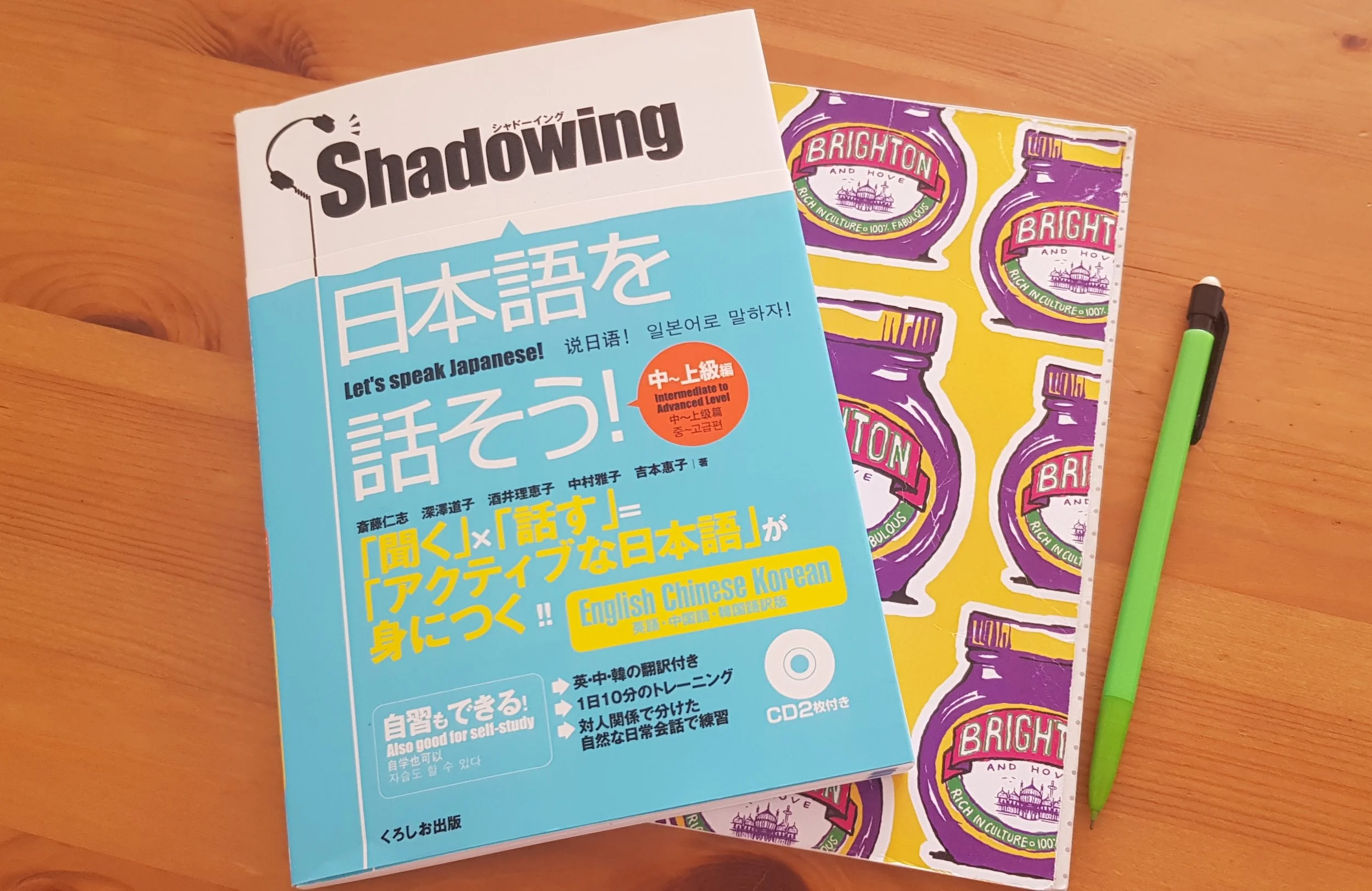

I didn’t have to look far to find a great shadowing resource – there is a popular book and CD combo called Shadowing: Let's Speak Japanese. It comes in two levels - beginner/intermediate, and intermediate/advanced. I ordered the latter from Amazon Japan, and followed the directions in the book. Every day for a month!

What is shadowing?

Most people are familiar with “listen and repeat” in language learning contexts. You listen to a conversation line-by-line and repeat each sentence after the recording.

Shadowing is different from simple “listen and repeat” in that you start speaking while the person on the audio is still talking. You echo the speaker 1 or 2 seconds after they speak, and talk over them.

If you tried to do this with long-form listening materials, even in your native language, it would be impossible – you’d get lost. And you wouldn't gain much phonetics or speaking practice by doing this.

So in shadowing, you use very short passages. The goal is to be able to produce the dialogue with perfect pronunciation, as close to the recorded audio as possible.

To do that, we need to break the process down into steps.

The book I bought was quite prescriptive, which at first seemed intimidating but in practice I found very helpful.

It suggests practising shadowing for 10 minutes a day, and doing one section o of the book (about 10 short conversations of about 4-5 lines each) continuously for 2-3 weeks.

So that’s what I did, following this process from the book to the letter.

How to do shadowing - step by step:

1) Find material at the right level for shadowing. Specifically, choose a short dialogue that is easy to read and understand, but difficult to say with fluency.

[Note from me (Fran): If you already have a Japanese textbook you’re using, you don’t need to buy a separate shadowing book. Use the short dialogues in your textbook.]

2) Listen to the audio and/or read the script, checking that you understand the conversation and looking up any words or expressions you don't know. You’re going to be repeating this conversation over and over, so it’s important that you understand what you’re saying, or the exercise is pointless.

3) Listen to the script and follow along with your finger.

4) Listen to the script and repeat the dialog in your head, without vocalising. That’s right – without speaking or moving your lips, silently repeat the dialogue a few seconds after the speaker.

5) Listen while visually following the script, and say the dialogue aloud a few seconds after the speaker. You’ll be talking over them.“The objective…is to keep up with natural speed, so think of it as a work out for your mouth when you practise.”

6) Without looking at the script, play the audio and say the dialogue aloud a few seconds after the speaker.

7) Without using the script, shadow the audio while thinking about the meaning of the conversation. Think about the emotions of the people in the conversation and the context.

Shadowing moves words and phrases from your passive to your active vocabulary

I followed a few steps from this process every day for at least 10 minutes. In a month, I did two sections of the shadowing book.

That’s not very much, really – 25 or 30 short conversations. But I felt like the words and phrases wormed their way into my spoken Japanese.

Here are a few examples:

1) I was talking to a friend about British weather, and the word 土砂降り(doshaburi, downpour) came out of my mouth. I’ve seen, heard and read that word before. But I don't think it’s ever been a part of my active spoken vocabulary.

2) I went for coffee with a Japanese friend and we were talking about something I feel quite sceptical about, when the phrase そうかな… (sou ka na? “I don’t think so?”) popped out of my mouth. Again, I’ve heard Japanese people say that phrase. But I don't think I’ve ever actually said it before.

Shadowing moved these words from my passive vocabulary into my active vocabulary. I kind of own them now – they’re part of my speech.

This shows how important it is to choose shadowing material that fits the way you want to speak. And it’s a good example of why you probably shouldn't shadow anime, unless you want to sound like a pirate or a robot cat.

Record yourself!

I also watched about half of Dogen’s Japanese Phonetics series on YouTube and made notes. I started to get into the habit of looking up the pitch accent of words I wasn't sure about.

And I recorded myself speaking, and listened back to it, comparing it line by line to the recording.

Like most people, I don't even like listening to recordings of myself in my native language. So listening to myself speak Japanese was quite painful. But I definitely noticed speaking habits I have that I didn't know I had, and little mistakes I didn't know I was making.

The downside of recoding yourself (as opposed to just shadowing) is that recording yourself and listening back to it takes about three times as long as just shadowing would.

Give it a go!

I found it easier to speak over the dialogue wearing headphones. But because shadowing involves talking to yourself, you can’t really do it on public transport. That being said, I found it relatively easy to squeeze 10 minutes of practice into my day. I did it before work, or afterwards when I got home.

Shadowing has its critics (if you want to read more about that, google “does shadowing work?”). But if you want to improve your spoken Japanese, I really recommend that you give it a try. I feel like it worked for me. Maybe it’ll work for you too?

Like me, you might find your vocabulary for British weather expanding! Or you might learn a new way to be sceptical. Same thing really.

Links:

Amazon links with an asterisk* are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

Japanese Phonetics by Dogen https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jakXVEUTT48 (some of these fantastic videos are free; the complete series is available to Dogen’s Patreon supporters)

Shadowing: Let's Speak Japanese! Beginner to Intermediate (Book & Audio CD) https://amzn.to/2XSzW0H *

Shadowing: Let's Speak Japanese! Intermediate to Advanced Level (Book & Audio CD) https://amzn.to/2XQCwEk *

Please note that both books are likely to be slightly cheaper on Amazon Japan:

シャドーイング-日本語を話そう-初〜中級編 https://www.amazon.co.jp/シャドーイング-日本語を話そう-初〜中級編-斎藤-仁志/dp/4874243541/

シャドーイング-日本語を話そう-中~上級編 https://www.amazon.co.jp/シャドーイング日本語を話そう-中~上級編-斎藤仁志;深澤道子;酒井理恵子;中村雅子;吉本惠子/dp/4874244955/

ブライトンの日本語教室で手伝ってくれる素晴らしいボランティアの皆さん

ブライトン近郊に住んでいる日本人から「ステップアップジャパニーズでボランティアできますか?」というメールを時々いただきます。

こういうメールをいただいて、私は毎回とても嬉しく思います。近くに住んでいる日本人が私の日本語教室を見つけて、しかも手伝いに行きたいと思ってくださることは、とてもありがたいと思います。

今年度、日本人のボランティアは授業に手伝いに来てくださっただけではなく、イベントやワークショップも一緒に開くことができました。

イギリスのボランティア・ウィーク(Volunteers’ Week)をご存知ですか。

(英語版はこちら Click here to read this article in English)

ブライトン近郊に住んでいる日本人から「ステップアップジャパニーズでボランティアできますか?」というメールを時々いただきます。

こういうメールをいただいて、私は毎回とても嬉しく思います。近くに住んでいる日本人が私の日本語教室を見つけて、しかも手伝いに行きたいと思ってくださることは、とてもありがたいと思います。

今年度、日本人のボランティアは授業に手伝いに来てくださっただけではなく、イベントやワークショップも一緒に開くことができました。

イギリスのボランティア・ウィーク(Volunteers’ Week)をご存知ですか。毎年6月1日〜7日に行われる感謝のキャンペーンです。手伝ってくださるボランティアの皆さんに感謝を込めて「ありがとう」とお伝えする一週間です。

それでは、2019〜20年のボランティアの皆さんへ大きな「ありがとう!」をお伝えしたいと思います。

サマープログラムに手伝いに来てくださったありあさんへ。

生徒たちと一緒にゲームをしながら、「ホットドッグ」の正しい発音を教えてくださってありがとうございます。

STEP 1(初級)とSTEP 2(初級2) の生徒さんと優しく話して、自信を持たせてくださった真里さんへ。

そして先月、素晴らしい折り紙のワークショップを一緒に開いてくださったさやさんへ。

皆さん、ありがとうございました!

Is it Shinbun or Shimbun?

It’s both. And it’s neither.

Beginner students often ask whether “shinbun” or “shimbun” (the word for “newspaper” in Japanese) is correct.

You’ll see both spellings...and books about the Japanese language don’t seem to be able to agree either.

If you look at the two most popular Japanese beginner textbooks, Genki has “shinbun”, whereas Japanese for Busy People has “shimbun” and also “kombanwa”.

But why?

It’s both. And it’s neither.

Beginner students often ask whether “shinbun” or “shimbun” is the correct spelling of the word for “newspaper” in Japanese.

You’ll see both spellings… and books about the Japanese language don’t seem to be able to agree either.

If you look at the two most popular Japanese beginner textbooks, Genki has “shinbun”, whereas Japanese for Busy People has “shimbun” and also “kombanwa”.

But why?

Well, there are different ways of writing Japanese in romaji (roman letters i.e. the alphabet). All romaji is an approximation, and there are two different major systems, both used widely.

In elementary school, Japanese kids learn Kunrei, the government’s official romanization system. Kunrei is more consistent, but not particularly intuitive for non-Japanese speakers.

In the Kunrei system:

しょ is written as “syo”

こうこう is written as “kookoo”

But textbooks for people learning Japanese tend to use the Hepburn system, which is easier for non-native speakers. Modernised Hepburn writes しょ as “sho” and こうこう as “kōkō”.

"N or M?"

Under the older Hepburn system of romaji, a ん (n) before a "b" or "p" sound used to be written as m. This gave us romaji spellings like shimbun and sempai. (The Kunrei system, on the other hand, never used this rogue "m" at all).

When Modernised Hepburn was introduced in 1954, the "m" rule was dropped. Since 1954, both major systems have said that these words should be written as shinbun and senpai.

So shimbun-with-an-m hasn't been officially used since 1954...but it is still the preferred romanization of several major Japanese newspapers: Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun.

So it seems like shimbun-with-an-m is still with us.

"So which is better?"

Arguably, “shimbun” is closer to the pronunciation of the word. There IS a sound change going on here – before a “p” or “b” sound in Japanese, the ん sounds more like “m” than “n”.

But "shinbun" is more consistent, and personally I prefer it - especially if you’re still learning kana.

There is no ‘m’ hiragana, and I don’t want you wasting your time looking for it on your kana chart.

"Which is more common?"

I don’t know. But it kind of doesn’t matter which one is more common: the Japanese way to write the word for newspaper isn't “shinbun” or “shimbun”. It’s not really even しんぶん. The Japanese word for newspaper is 新聞.

Which brings me neatly onto my next question...

“Why are you writing it in romaji anyway?"

Some people say that the shimbun/shinbun thing is a slightly pointless question. Everyone should just learn the kana, and then we wouldn't have this problem, right?

But romaji isn’t just read by people learning Japanese. Romanised stations and place names and even people's names are read by millions of people visiting Japan who don’t know Japanese.

And for people who don’t speak Japanese (especially English speakers), it's easier to guess the pronunciation of “shokuji” than “syokuzi”.

So, while the current system is a bit of a muddle, it's the best thing we've got. I think we can all agree on that.

(First published February 12, 2016. Updated June 21, 2019)

A Japan Pub Quiz!

I wrote a little bit about my Japanese volunteers who come to help out at class and with events and workshops.

But I’m also helped enormously at Step Up Japanese by my students, who organise events, give me great ideas, and share helpful feedback on how to make class better.

I wrote a little bit about my Japanese volunteers who come to help out at class and with events and workshops.

But I’m also helped enormously at Step Up Japanese by my students, who organise events, give me great ideas, and share helpful feedback on how to make class better.

Huge thanks to STEP 4 student Sheen-san for organising this fantastic Japan-themed quiz for us last week. And thank you all for coming!

またしましょうね。Let’s do it again sometime!

Our Fantastic Volunteers

Sometimes, Japanese people write and ask if they can volunteer at Step Up Japanese.

I’m always very happy that Japanese people in Brighton and Hove have found my school and want to visit and help out.

This year, a number of Japanese volunteers have helped out in class and with events and workshops.

This Volunteers Week, I’d like to say a big thank you to my 2018-19 volunteers!

(Click here to read this article in Japanese 日本語版はこちら)

Sometimes, Japanese people contact me and ask if they can volunteer at Step Up Japanese.

I’m always very happy that Japanese people in Brighton and Hove have found my school and want to visit and help out.

This year, a number of Japanese volunteers have helped out in class and with events and workshops.

This Volunteers Week, I’d like to say a big thank you to my 2018-19 volunteers!

Aria-san, who came to help out with Summer Programmes in 2018. Thank you for playing games with my students and teaching them how to say ホットドッグ (hotto doggu; hot dog):

Mari-san, for chatting with STEP 1 and STEP 2 students and encouraging them to speak with confidence:

And Saya-san, for teaching us incredible origami!

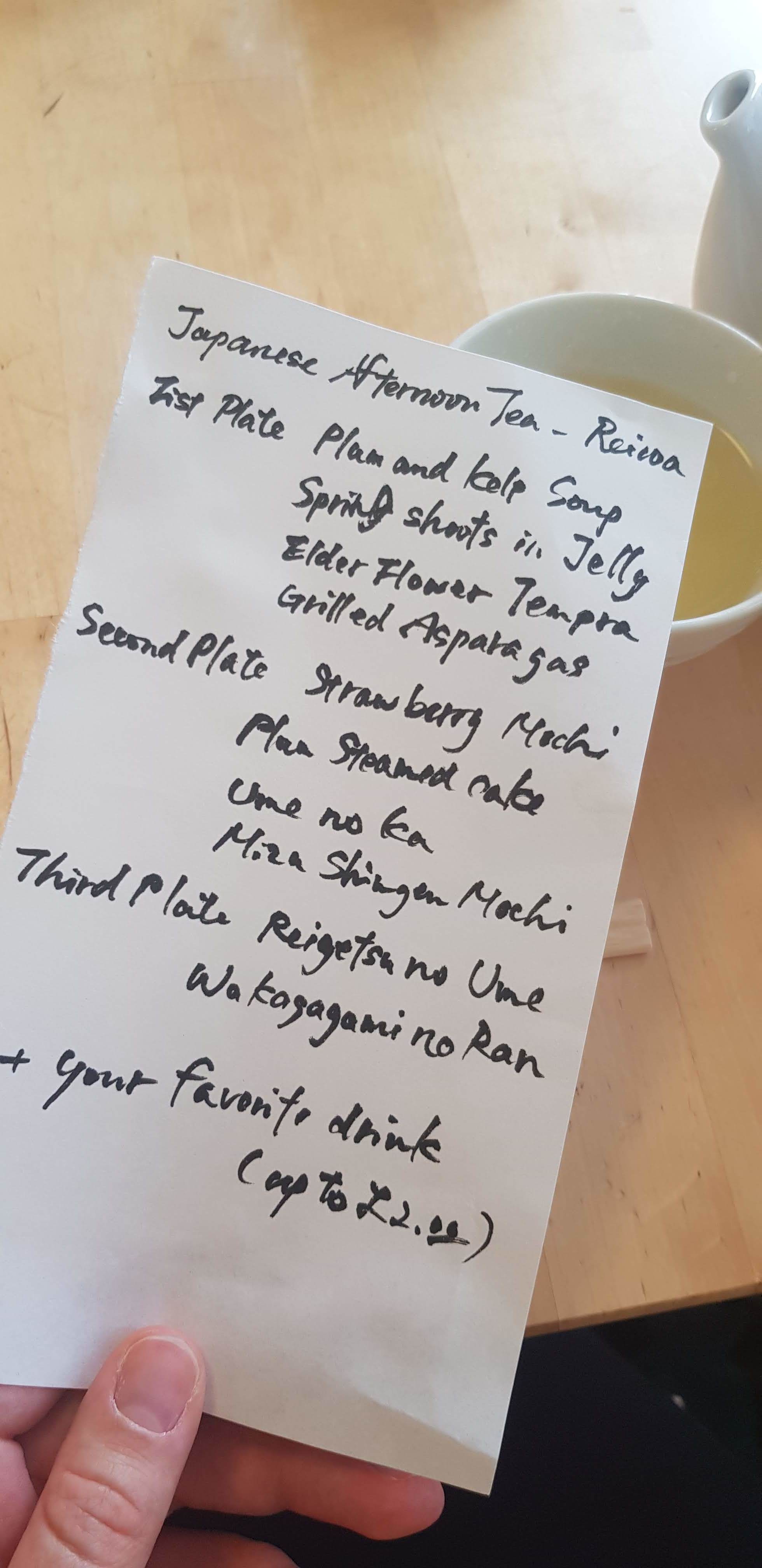

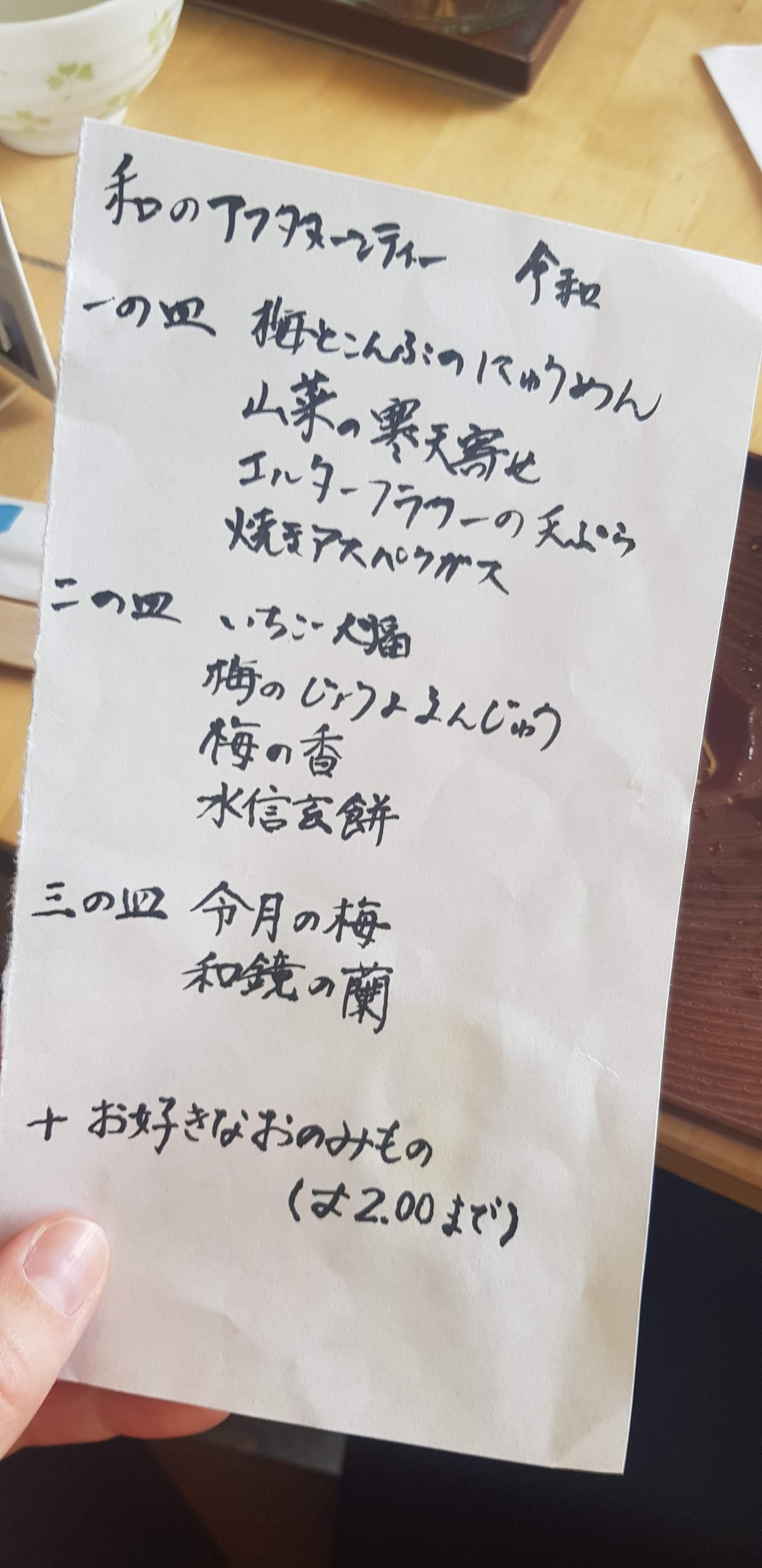

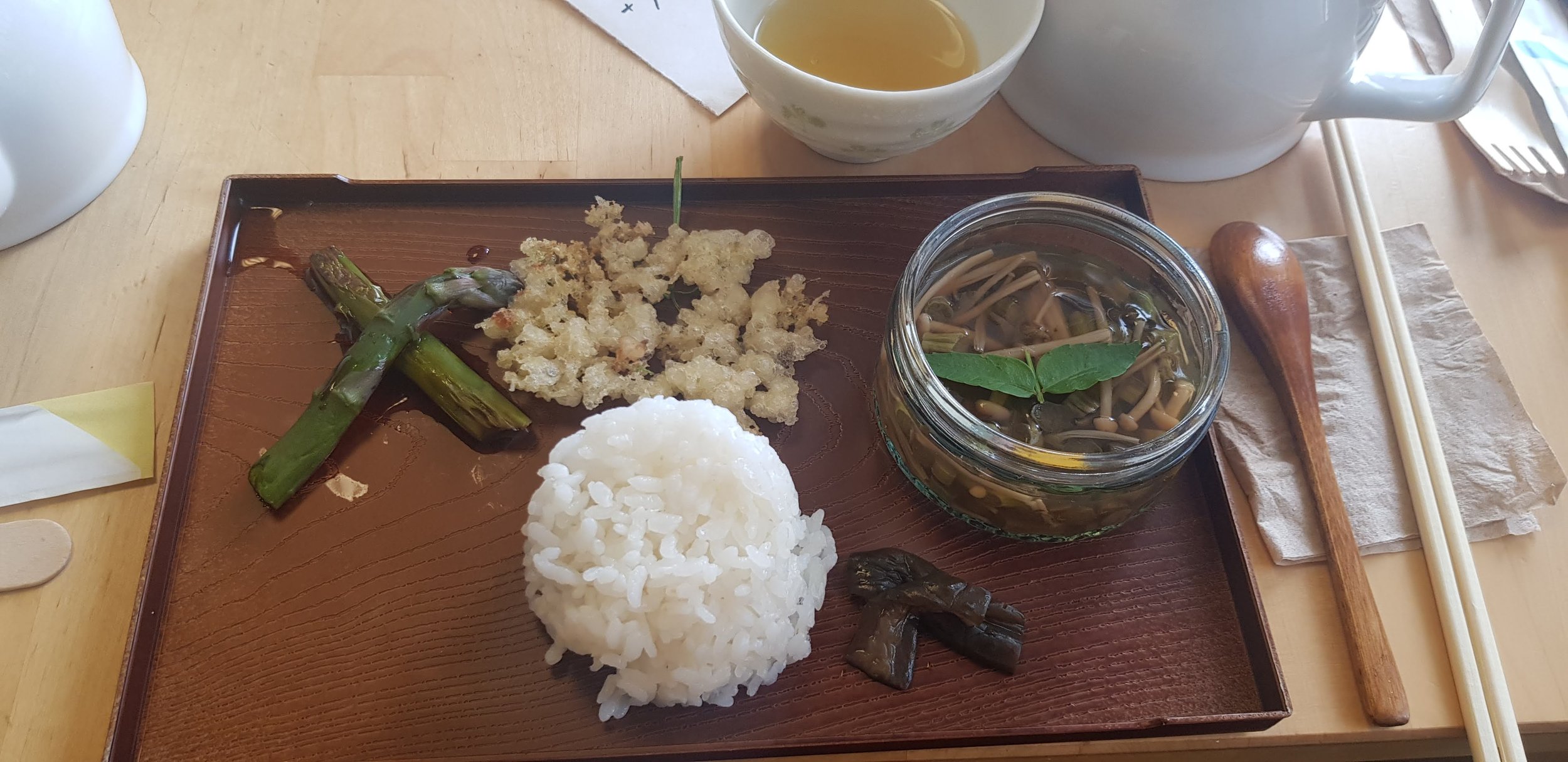

Reiwa Afternoon Tea at Cafe an-an!

My students and I went to eat these amazing Japanese sweets at Cafe an-an in Portslade.

We had Japanese afternoon tea themed around Reiwa (令和), the new Japanese era which started on May 1st.

My favourite was the elderflower tempura (so good!) and 水信玄餅 mizu shingen mochi - the clear "raindrop" mochi.

Also, I learned that the Japanese word for elderflower is エルダーフラワー (erudaafurawaa).

My students and I went to eat amazing Japanese sweets at Cafe an-an in Portslade.

We had Japanese afternoon tea themed around Reiwa (令和), the new Japanese era which started on May 1st.

My favourite was the elderflower tempura (so good!) and 水信玄餅 mizu shingen mochi - the clear "raindrop" mochi.

Also, I learned that the Japanese word for elderflower is エルダーフラワー (erudaafurawaa).

Noriko-san, ありがとうございました! Thank you very much for having us!

What is the Japanese Calendar, and what year is it?

Did you know that Japan has its own numbering system for the years? As well as the Gregorian calendar (the same calendar used in the west, the one that says it's 2019 now), Japan uses another system which names years after the reign of the emperor.

(The western calendar is commonly used too - and the two systems can be used interchangeably.)

So, what's the date?

Did you know that Japan has its own numbering system for the years? As well as the Gregorian calendar (the same calendar used in the west, the one that says it's 2019 now), Japan uses another system which names years after the reign of the emperor.

(The western calendar is commonly used too - and the two systems can be used interchangeably.)

So, what's the date?

After Emperor Naruhito ascended to the Japanese throne on 1st May 2019, the new Japanese era Reiwa (令和) began.

This means that 2019 has two different names in Japanese: the first part is named after the previous era. And the second part is named after the new era.

So the period between 1st January and 30th April 2019 was 平成31年 (heisei sanjuuichi nen; Heisei 31).

And the period from 1st May to 31st December 2019 is 令和1年 (reiwa ichi-nen; Reiwa 1) or 令和元年 (reiwa gan-nen; gan-nen being a special word referring to the first year of an imperial reign).

1st June 2019, therefore, can be written in Japanese as:

令和1年6月1日

Reiwa ichi-nen roku-gatsu tsuitachi

(Japanese dates go from big to small: year → month → day)

Or even just as:

1/6/1

Cool, huh?

A year in seven days

Emperor Hirohito died in the 64th year of his reign, on 7th January 1989. So the "year" Showa 64 was only seven days long. The rest of 1989 (from January 8th onwards) got the name Heisei 1.

Date-spotting in Japan

The Japanese date system is commonly used in New Year’s greetings. You might see the year written in kanji on a New Year’s card too.

Can you read the year on this card?

Image source: yubin-nenga.jp

You can also see the Japanese year on coins and banknotes in Japan.

What year is this from?

Image: Wikipedia

You don't need to memorise the dates of all the emperors, though (unless you want to). There are apps and online converters that will tell you any year in the Japanese equivalent.

Should we start calling 2019 “Elizabeth 67”?

If this all seems strange, remember that we do this in other languages, too.

When we talk about "the Victorian era" (the years of Queen Victoria’s rule) or “the Victorians” (people who lived during that time), that's basically the same thing.

We just don’t name the individual years after the current ruler. We could if we wanted, though, I guess...?

Top image source: Wikipedia