Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

How to Read The Japanese News (Or Any Japanese Website!) with Rikaichan

When I first moved back to Brighton from Japan I had a lot of time on my hands. I also didn't have a job, so I was desperate for free Japanese reading material.

So I started borrowing Japanese books from the library.

This plan was not exactly a success. It turns out reading Twilight in Japanese is only slightly more entertaining than reading it in English.

But we are really lucky to live in a world where, if you have internet access, you can read just about anything you want in Japanese online. And the news is a great place to start.

When I first moved back to the UK from Japan I had a lot of time on my hands. I also didn't have a job, so I was desperate for free Japanese reading material.

So I started borrowing Japanese books from the library.

This plan was not exactly a success. It turns out reading Twilight in Japanese is only slightly more entertaining than reading it in English.

But we are really lucky to live in a world where, if you have internet access, you can read just about anything you want in Japanese online. And the news is a great place to start.

If you can't read fluently yet, looking at a page of Japanese text can be intimidating. You don't know the meaning of the word, or even how to sound it out.

You need a dictionary - a really smart free one like Rikaichan. Rikaichan is a browser add-on that works as a pop-up dictionary. I used it every day for years, and I love it. Let's take a look at how it works, and start reading the news!

How Rikaichan works

Here we are on the website of the Asahi Shimbun, one of Japan's largest national newspapers.

I hover the cursor over the word 音楽. Rikaichan's little blue pop up tells me the reading of the word (おんがく ongaku) and what it means - "music".

Rikaichan also shows us the dictionary entries for individual kanji (Chinese characters).

Here, it's showing 音, the first character in the word 音楽, and telling us that 音 means "sound".

Learn where words begin and end

Standard written Japanese doesn't have spaces between words so if you're looking at unfamiliar words, it can be hard to know where each word starts and finishes.

Rikaichan is pretty smart at doing that bit for you.

Here, in the below example, it knows that 九州 (Kyushu island) is one word, and 豪雨 (torrential rain) is the next, separate word.

How to get it

So that's what Rikaichan does. Here's how to get started with it!

1) Get the right browser

Rikaichan and its "little brother" Rikaikun are for the web browsers Firefox and Chrome. If you're not using one of those, you'll need to download the browser first.

It's worth it. I used Firefox religiously for years just so I could use Rikaichan to get my morning news.

As far as I know the add-on doesn't work on mobile, unfortunately. (There's a similar-looking app called Wakaru for iOS - if you've used it, let me know what you think.)

2) Install Rikaichan or Rikaikun

Which one do you need? Rikaichan and Rikaikun are the same add-on, but for Firefox and Chrome. So, download and install Rikaichan from the Mozilla add ons page, or Rikaikun from the Chrome Web Store.

3) Download a dictionary

Rikaichan needs a dictionary to pull readings and meanings from, so after you've installed the add-on, you'll be prompted to install at least one dictionary file. If English is your first language, you want the "Japanese - English" dictionary.

I recommend installing the "Japanese Names" dictionary too, so that Rikaichan can identify common names when they pop up. That way, it'll know that 中田 is Nakada, a common Japanese surname, and doesn't just mean "middle of the ricefield".

4) Turn Rikaichan on

You probably won't want Rikaichan on all the time. Sometimes you'll want to read without a dictionary, and sometimes you won't be reading Japanese. You can turn it off and on when you like. Turn Rikaichan on, and let's give it a go.

Read everything!

Years ago when I started using Rikaichan, I set myself a challenge to read one headline with it every day.

Next, I made myself read three headlines per day. Then five. Then the first paragraph of an article. Eventually I was reading entire news articles, and using the dictionary less and less.

These days I get the Asahi Shimbun news straight to my inbox, because I don't need to look up words often enough to use Rikaichan any more.

But it was a completely invaluable part of my language learning journey. And it's definitely more interesting than reading Twilight in Japanese.

Updated 23rd Oct 2020

Why Does Everybody Forget Katakana?

I'll let you into a secret. I used to hate katakana.

Students of Japanese tend to start with its two phonetic alphabets. We start with hiragana, the loopy, flowing letters that make up all the sounds of Japanese.

Then we move on to katakana - all the same sounds, but in angular blocky font.

Hiragana seems fairly straightforward, I think. And when you start learning Japanese everything you read is written in hiragana, so by reading you constantly reinforce and remember.

Katakana? Not so much.

I'll let you into a secret. I used to hate katakana.

Students of Japanese tend to start with its two phonetic alphabets. We start with hiragana, the loopy, flowing letters that make up all the sounds of Japanese.

Then we move on to katakana - all the same sounds, but in angular blocky font.

Hiragana seems fairly straightforward, I think. And when you start learning Japanese everything you read is written in hiragana, so by reading you constantly reinforce and remember.

Katakana? Not so much.

The katakana "alphabet" is used extensively on signs in Japan - if you're looking for カラオケ (karaoke) or ラーメン (ramen noodles) you'll need katakana.

But if you're outside Japan, then beyond the letters in foreign names, you probably don't get a lot of exposure to katakana.

I think that's why a lot of beginning students really struggle to remember katakana.

Here are a couple of suggestions:

1) Use mnemonics

I learned katakana using mnemonics. For example, I still think katakana ウ (u) and ワ (wa) look super similar - I remember that ウ has a dash on the top, just like hiragana う (u) .

2) Practice, practice, practice

I'm not a huge fan of having you simply copy letters over and over again, but there is something to be said for "writing things out". By writing letters down, you activate muscle memory, which helps you remember. So get writing katakana!

3) Start learning kanji

It might feel like running before you can walk, but starting to read and write kanji (Chinese characters) before your katakana is completely perfect can be a good option.

Kanji textbooks have the Chinese readings of the characters in katakana, so learning kanji is also really good katakana practice.

And maybe, just maybe, you'll turn into a katakana lover?

Updated 23rd Oct 2020

A Year of Monthly Japanese Learning Challenges

How do you keep practising Japanese, even when it doesn’t seem relevant? How do you stay motivated, when your life and your motivations change?

At the beginning of 2019, I decided to set myself a series of monthly Japanese study challenges. I’d do one every other month, and blog about it.

In January, I tried to speak Japanese every day for a month. This was probably the hardest challenge, from a logistical perspective. I don’t live in Japan, and we don’t speak Japanese at home (much). At the time, I was also working another job three days a week, where I wasn’t using Japanese at all. So speaking Japanese every day was, quite literally, a challenge.

How do you keep practising Japanese, even when it doesn’t seem relevant? How do you stay motivated, when your life and your motivations change?

At the beginning of 2019, I decided to set myself a series of monthly Japanese study challenges. I’d do one every other month, and blog about it.

In January, I tried to speak Japanese every day for a month. This was probably the hardest challenge, from a logistical perspective. I don’t live in Japan, and we don’t speak Japanese at home (much).

At the time, I was also working another job three days a week, where I wasn’t using Japanese at all. So speaking Japanese every day was, quite literally, a challenge.

But this was a great start to the year and probably one of my favourite things I’ve done using Japanese. Plus, I got to eat katsu curry at cafe an-an in Portslade and chalk it up as Japanese practice:

I Tried to Speak Japanese Every Day for a Month (Without Being in Japan)

In March, I tried shadowing every day.

What is shadowing? Most people are familiar with “listen and repeat” in language learning contexts. You listen to a conversation line-by-line and repeat each sentence after the recording.

Shadowing is different from simple “listen and repeat” in that you start speaking while the person on the audio is still talking. The goal is to be able to produce the dialogue with perfect pronunciation, as close to the recorded audio as possible.

I really enjoyed this challenge, and I also discovered that you can practise shadowing (quietly) in hotel rooms, waiting rooms, and even on the bus.

What is Shadowing and Can it Improve Your Spoken Japanese? I Tried Shadowing Every Day for a Month

In May, I read Japanese books every day. This was really fun, too, and not so hard once I got into a routine. If you get in the habit of taking a book with you everywhere you go, reading every day is relatively easy:

How to Read More in Japanese – I Tried Reading in Japanese Every Day for a Month

In July, I decided to play Japanese video games every day for a month, because who says challenges have to be challenging?

I played Japanese video games for about 20 minutes a day for a month, and here’s what I learned: six reasons to play video games in a foreign language.

This is not a “how to” post. I’m not going to tell you how to “learn Japanese in a week just by playing video games” or to claim this is a “quick route to fluency” (it’s not, namely because there is no quick route to fluency, just an endless and potentially very enjoyable road trip).

Instead, I’m just going to share some reflections on the very fun experience that was playing Japanese video games every day.

How to Practise Japanese by Playing Video Games Every Day

(IMAGE SOURCE: NINTENDO)

In September, I tried to watch Japanese TV every day. This is where the monthly challenges really started to come unstuck. September was a busy month, and life got in the way.

I also discovered that when a challenge isn’t very challenging, I don’t personally find it very motivating!

One fantastic thing that came out of this experience, however, was the idea for my new course Learn Japanese with Netflix! … but then covid-19 happened, which meant the Netflix course only ran for a few weeks. I hope to run it, or a similar course, again in the future.

Watching Japanese TV Every Day for a Month (Or, What to Do When Things Don't Go To Plan)

After that I took a two month break, and then in December, I got well and truly back on the horse, and spent a month practising handwriting kanji from memory every day.

I really enjoyed the routine of practising kanji again. I find kanji practice surprisingly relaxing - and I mentioned this to some students, who also said they find kanji writing practice relaxing, even meditative. Little and often is probably key.

"How Did You Learn Kanji?"

What next?

The process of setting bi-monthly goals was a stimulating and enjoyable experience, and I might repeat it another year, but I’m not doing monthly challenges in 2020.

We’re a few months into 2020, and due to covid-19, this year is already shaping up to be significantly more challenging than 2019.

2020 has already proved to be a year of radical change, for students at Step Up Japanese as well as for people all over the world. In March 2020 I moved all lessons online - another new challenge, but an enjoyable one.

I hope you stay healthy and safe throughout 2020, and that if Japanese study is a part of your life at the moment, that you enjoy it and have fun. And if life gets in the way sometimes….that’s okay too.

What's the Difference Between Mina and Minna (And Why Does It Matter Anyway?)

If you watch Japanese TV or anime (or are paying attention in class) you've probably come across the Japanese word mina-san (皆さん) meaning "everybody".

But what's the difference between mina and minna? What's mina-sama all about? And ... does it actually matter?

Mina-san, konnichiwa! (皆さん、こんにちは ) Hello everybody!

If you watch Japanese TV or anime (or are paying attention in class) you've probably come across the Japanese word mina-san (皆さん) meaning "everybody".

But what's the difference between mina and minna? What's mina-sama all about? And ... does it actually matter?

1.皆さん Mina-san

Mina means "everybody", and it's commonly used with "-san" (the honorific suffix you put on the end of people's names to be polite).

Mina-san is often used when addressing a group of people, especially when they don't know either other too well or the situation calls for a slightly more formal greeting.

I find myself using mina-san in class a lot, which makes sense - I’m addressing a group of people.

As you might expect, Japanese YouTubers say “mina-san konnichiwa” a lot too ("hi guys!")

These example sentences from jisho.org should give you a good idea of the kinds of situation when mina-san is used:

2.みんな Minna

Also common is minna, which is just a spoken form of mina. Minna is more casual than mina.

Examples from jisho show us that people also use minna when they talk about everyone, as well as when addressing groups:

3. Beware! It’s not みんなさん minna-san

You can't mix them up and use minna-san though. That's incorrect.

Probably no one will mind or notice in a casual situation, but if you're trying to be polite, stick with mina-san. Or you can even go more polite with...

4. 皆様 Mina-sama

In more formal situations, the -san suffix is switched up to the more polite/formal -sama.

Mina-sama functions a lot like "ladies and gentlemen", or “esteemed guests”, and is used in writing, and in announcements:

Why does this matter?

Well really, which word you use is going to depend on the situation.

Mina-sama is super formal and it would sound weird if you use it with your friends. Likewise, minna is pretty casual and might not be appropriate in a business setting.

A lot of gaining fluency in a language is about choosing the right word for the right situation. The more examples you can read, and the more you can expose yourself to the Japanese language, the more these distinctions will start to make sense.

Mina-san, if you'd like to learn more Japanese with me, click here to check out my new online Japanese language courses!

First published 9th June 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

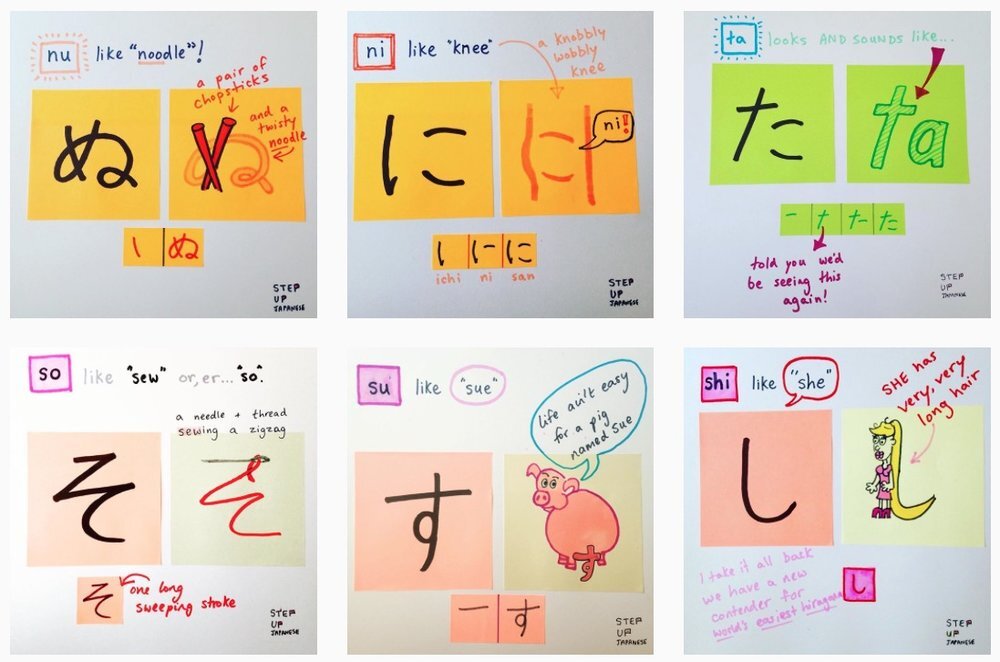

How to Learn Hiragana and Katakana using Mnemonics

I finally got around to going through the mid-course feedback from my students and drawing up plans to incorporate some of what you asked for into the rest of the course. Several learners mentioned the importance of learning the kana early on.

Learning to read Japanese can be a daunting task. The Japanese language has three distinct "alphabets" (four if you count romaji!) and learning kanji is a task that takes years. You can learn the kana (hiragana and katakana) pretty quickly, though, if you use the most efficient way to memorise them - mnemonics.

Hi! This article was first published in April 2017. I updated it recently (April 2020) and fixed some broken links.

This week I finally got around to going through the mid-course feedback from my students and drawing up plans to incorporate some of what you asked for into the rest of the course.

Several learners mentioned the importance of learning the kana early on.

Learning to read Japanese can be a daunting task. The Japanese language has three distinct "alphabets" (four if you count romaji!) and learning kanji is a task that takes years.

You can learn the kana (hiragana and katakana) pretty quickly, though, if you use the most efficient way to memorise them - mnemonics.

Hiragana and Katakana are the "building blocks" of the Japanese written language. Students in my beginner Japanese classes mostly start with the romaji edition of 'Japanese For Busy People'*, because my priority is to get you speaking from day one, and to spend class time on speaking as much as possible. Reading and writing is mostly set as homework.

But if you want to learn to read Japanese, you definitely need to start by learning hiragana - the 46 characters that make up the first basic Japanese “alphabet”. But how to remember them?

The best, quickest, most fun method is to associate each character with a picture that it (clearly or vaguely) looks like, ideally also using the sound of the letter.

Hiragana and katakana are pretty simple, so associating each character with a picture is super easy.

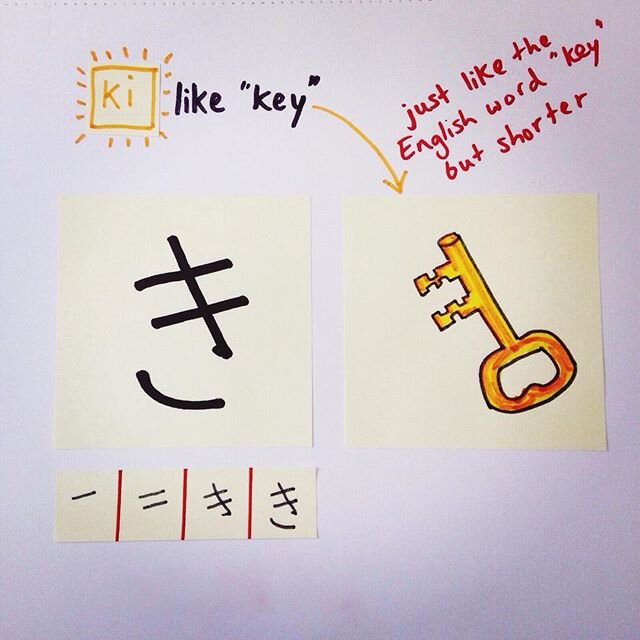

Here's hiragana き (ki), which we can imagine is a picture of a KEY. My image of akey is an old-fashioned one. Yours might be modern and spiky. Or it might have wings on it and be flying about getting chased by Harry Potter on a broomstick.

The point is to think of a strong visual image that makes the picture of the key stick in your mind:

Of course, you need to learn to read words and sentences too. So as well as learning each letter, you need to practice writing and reading. This where the mnemonic really sinks in.

Memorisation doesn't help you remember. What helps you remember is active recall.

Let me give you an example.

You're reading a sentence and come across the word きのこ (kinoko, mushroom). You're staring at the letter き - "which one was that again?" and struggle a little bit to remember it.

Then you remember - aha! it's the KEY! This is ki.

This process of active recall - pushing a little bit to remember something - is the process that cements the mnemonic in your mind.

For me, one of the great thing about using mnemonics to remember the kana is that when I explain the system to learners, they often tell me that's what they're doing anyway, even if they don't have a name for what they're doing:

"Oh yes, that's how I remember む too - it's a funny cow's face! MOO"

"No, む is a man saying MO-ve!"

I've also found - luckily for me - it doesn't matter seem to matter if the actual picture is rubbish. (You don't even have to draw them, I just did this to help my students out and to share the idea).

What's important is that the picture in your head is super clear.

...and once you finish hiragana, you can do the whole thing again for katakana (the second basic Japanese alphabet):

You can find the whole set of hiragana and katakana mnemonics on instagram with the hashtag #stepupkana - please check it out and let me know what you think.

I'd love to hear what mnemonics you use to help remember the kana - let me know in the comments or add your story to the instagram posts for that character.

*Links with an asterisk * are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

First published April 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

Plateaus in Language Learning and How to Overcome Them

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth. I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

Do you remember the first conversation you ever had in a foreign language?

The first three years I was learning Japanese I basically studied quite hard for tests and barely opened my mouth.

I liked kanji, and what I saw as the oddness of the Japanese language. Three "alphabets"! A million different ways of counting things! I liked hiragana - so pretty! I studied hard and thought my university Japanese exams were easy.

Then, on holiday in China, I met a Japanese woman (at a super-interesting Sino-Japanese cultural exchange club, but that's a story for another time). I tried to speak to her in Japanese. And I couldn't say anything.

I told this nice, patient lady that I was studying Japanese and she asked me how long I was staying in China for. I wanted to tell her I was going back to England next Thursday, but instead I said 先週の水曜日に帰ります (senshuu no suiyoubi ni kaerimasu) - "I'll go back last Wednesday."

OOPS.

I think about this day quite a lot because it shows, I think, that although I'd studied lots of Japanese at that point my communicative skills were pretty poor. I considered myself an intermediate learner, but I couldn't quickly recall the word for Wednesday, or the word for last week.

I realised at that point that I hadn't made much real progress in the last two years. The first year I zipped along, memorising kana and walking around my house pointing at things saying "denki, tsukue, tansu" (lamp, desk, chest of drawers) But after that my Japanese had plateaued.

So, I started actively trying to speak - I took small group lessons, engaged in them properly, did the prep work. I wrote down five sentences every day about my day and had my teacher check them. I met up with a Japanese friend regularly and did language exchange - he corrected my grammar and told me when I sounded odd (thanks, Kenichi!)

(Most of this happened in Japan, but like I said, you don't need to live in Japan to learn Japanese.)

And I came out of the plateau. I set myself a concrete goal - to pass the JLPT N3. The JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) is a standardised test in Japanese, for non-native speakers. N3 is the middle level - intermediate.

Once I’d passed that, I started aiming for N2, the next level up. I had some job interviews in Japanese, a terrifying and fascinating experience.

I wanted to get a job with a Board of Education, and a recruiter told me you needed N1 - the highest level of the JLPT - for that, so I started cramming kanji and obscure words. I was back on the Japanese-learning train.

I didn't pass N1 though, not that time.

And I was bored of English teaching and didn't want to wait to pass the test before I got a job using Japanese - that felt a bit like procrastinating - so I quit my English teaching job and got a job translating wacky entertainment news.

And after six months translating oddball news I passed the test.

That's partly because exams involve a certain amount of luck and it depends what comes up. But I also believe it's because using language to actively do something - working with the language - is a much, much better way of advancing your skills than just "studying" it.

Thanks to translation work, I was out of the plateau again. Hurrah!

When you're in the middle of something - on the road somewhere - it's hard to see your own development.

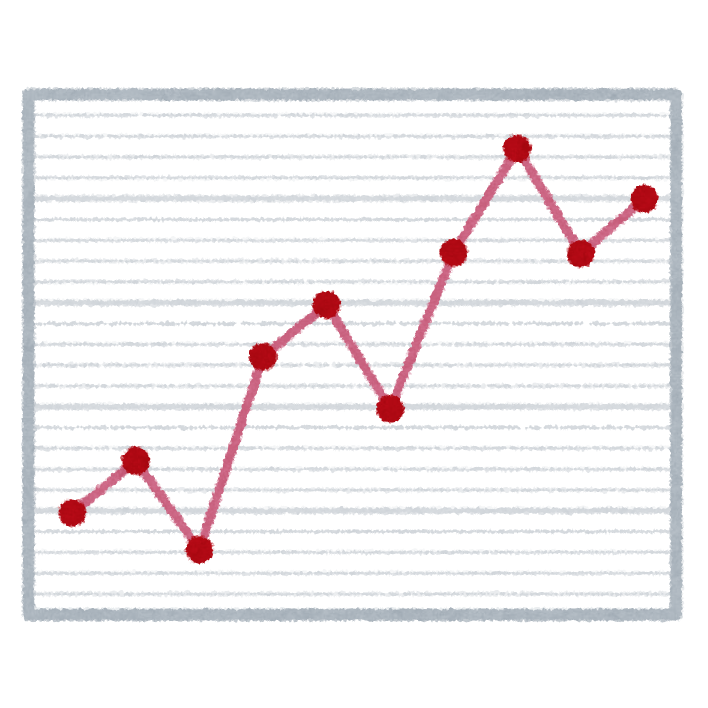

Progress doesn't move gradually upwards in a straight line. It comes in fits and starts.

Success doesn't look like this:

It looks like this:

And if you feel like you're in a slump at the moment, there are two approaches.

One is to trust that - as long as you're working hard at it - if you keep plugging away, you'll suddenly notice you've jumped up a level without even realising. You're working hard? You got this.

The other approach is to change something. Make a concrete goal. Start something new. Find a new friend to talk to or a classmate to message in Japanese. Talk to the man who owns the noodle shop about Kansai dialect. Write five things you did each day in Japanese. Take the test. Apply for the job. がんばる (gambaru; “try your best”).

Originally posted February 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

A Trip to Japanese Vegetable Farm Namayasai, or, Why I Had a Shungiku Omelette for Breakfast this Morning

Did you know there's a dedicated Japanese vegetable farm right here in Sussex?

I spent a Saturday with the Brighton Japan Club at Namayasai, near Lewes. Namayasai a Japanese vegetable farm owned by Robin and Ikuko, from Devon and Japan respectively, and is a Natural Agriculture farm - a specific type of organic farming that uses no pesticides / herbicides / artificial fertilisers.

Hi! This post was originally published 10 March 2017

Did you know there's a dedicated Japanese vegetable farm right here in Sussex?

I spent last Saturday with the Brighton Japan Club at Namayasai, near Lewes. Namayasai a Japanese vegetable farm owned by Robin and Ikuko, from Devon and Japan respectively.

Namayasai is a Natural Agriculture farm - a specific type of organic farming that uses no pesticides / herbicides / artificial fertilisers.

Robin started by giving us a tour of the farm, showing us their rainwater collection system, lots and lots of interesting plants, and compost toilet (I resisted the temptation to take a picture of the compost toilet).

We had a go at eating nettles, identified a nashi pear plant from its buds, spotted some daikon (sadly a bit frosted on top - the non-frosted ones were protected under a sheet so no photos of them):

...and even found some rhubarb!

As well as outdoor crops, the farm has a huge greenhouse filled with Japanese herbs and leafy vegetables.

Tour over, we had a quick stop for cake, and then it was time to do some actual work!

We mixed the compost and Robin told us we were going to plant 113 trays of seeds. That sounded like quite a lot to me, but he seemed confident we would get it all done.

Robin showed us how to plant the seeds with chopsticks (well it is a Japanese farm...)

We planted mitsuba (also known as "Japanese parsley" but more like shiso), shungiku (edible chrysanthemum) and daikon, amongst other things. The daikon seeds were bright orange, which was cool / surprising.

I can't remember what these guys were planting but it looked significantly more fiddly than what I was doing:

When we'd finished planting (yep, all 100-and-something trays), Robin sent us home with bags and bags of vegetables.

I spent the next four days eating massive amounts of green veg, which made me extremely happy.

It was a lot of fun - massive thanks to Robin for having us, and Tom at the Brighton Japan Club for organising!

As well as locally, Namayasai supplies lots of famous Japanese restaurants in London, and Robin and Ikuko also run a vegetable box scheme with collection points around Sussex which I now have my eye on.

They have lots of info about the veg box, the farm itself and work/volunteer opportunities on their website - please do check it out!

Originally posted 10 March 2017

Updated 31st March 2020