Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

"How Did You Learn Kanji?"

I had a friend in 2011 who also lived in Japan and was also learning Japanese. Like me, he hoped to be fluent one day. I told him that I was going to learn all 2136 common-use kanji by making up a mnemonic story for each one. He laughed at me, of course. I don’t blame him.

But this slightly convoluted method is the thing that took my Japanese kanji knowledge from beginner to advanced.

So here is the story of how I studied kanji, some suggestions for kanji practice, plus some advice from another friend who took a totally different approach to me. I hope you’ll find it useful!

I had a friend in 2011 who also lived in Japan and was also learning Japanese. Like me, he hoped to be fluent one day. I told him that I was going to learn all 2136 common-use kanji by making up a mnemonic story for each one. He laughed at me, of course. I don’t blame him.

But this slightly convoluted method is the thing that took my Japanese kanji knowledge from beginner to advanced.

So here is the story of how I studied kanji, some suggestions for kanji practice, plus some advice from another friend who took a totally different approach to me. I hope you’ll find it useful!

Learning kanji takes time

Written Japanese uses a mix of three “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji (Chinese characters).

Individual hiragana and katakana characters indicate sound only - the hiragana character あ makes the sound “a”, but it doesn’t have any meaning by itself. (Just like how the letter “B” doesn’t have any meaning by itself - it’s just a sound).

Kanji, on the other hand, indicate meaning as well as sound. For example, the kanji 木 means “tree”; 重 means “heavy”.

To read Japanese fluently, a student must be able to understand at least 2000 kanji. There is even an official list of the 2136 kanji that all Japanese children learn by the end of secondary school, called the jōyō kanji (常用漢字, meaning “regular-use kanji”).

The task of learning at least 2000 kanji is a major undertaking - even for Japanese people. That’s why students in Japan continue learning the jōyō kanji right up until the end of high school. And traditional methods of learning kanji tend to focus on rote memorisation, which is very inefficient.

The Heisig Method

When I got serious about learning kanji, in 2010, I did a bit of googling and stumbled across people talking about “the Heisig method”. This is the kanji study method introduced by James W. Heisig in his popular (and somewhat controversial) book ‘Remembering the Kanji I: A complete course on how not to forget the meaning and writing of Japanese characters’.*

The Heisig approach can be summed up as follows:

1) Learn the meaning of kanji

2) Learn the meaning of radicals

3) Memorise how to write kanji by making up descriptive mnemonic stories

You’ll note that reading kanji (how to pronounce them) does not feature on this list.

1) Learn the meaning of kanji

Heisig argues that before learning the readings of any kanji characters, it is more efficient to first learn the meanings. To this end, he gives each kanji an English keyword. For example, the kanji character 行 means “go”, so Heisig gives it the English keyword “going”.

By learning the meanings of kanji, the learner can guess at unfamiliar words.

I got to show off this ability years later in Okinawa, when my good friend Karli and I were looking at some artefact:

“What’s it made of?” she asked.

“I think it’s ivory.”

“Fran, why the hell do you know the Japanese word for ‘ivory’?”

“I don’t,” I said, pointing at the sign which had the word 象牙 on it. “But this one (象) "means ‘elephant’, and this one (牙) means ‘tusk’.”

2) Learn radicals

Heisig also puts a lot of focus on learning radicals - small parts which make up kanji. (He calls them “primitive elements”, but radicals is a more commonly-used term).

Radicals are the building blocks of kanji, and by learning to identify these constituent parts, you can “unpick” new and unfamiliar characters. Knowledge of radicals is also very helpful for looking up kanji in a dictionary.

For example, the kanji 明 (meaning “bright”) is made up of the two smaller parts 日 (“sun“) and 月 (“moon”). If the SUN and the MOON appeared in the sky together, that’d be pretty BRIGHT, right?

3) Make mnemonics

Using these radicals, Heisig argues that by making vivid and memorable stories, you can remember even complex kanji easily.

A common and simple example of a kanji mnemonic is 男, the character for “man”. The top half of this kanji is 田 “rice field“, and the bottom half is 力, “power”. So here’s the image: A MAN is someone who uses POWER in the RICE FIELD.

(If you’re not great at making up mnemonics, you can do what I did and copy other people’s funny stories from the Kanji Koohii website).

4) Practice writing by hand - from memory

Heisig says that in order to learn to read and recognise kanji characters, you should practise writing them. But rather than just copying them out endlessly, you need to use the power of active recall. He tells the student to use flashcards to test yourself on your ability to write the character from memory.

So for instance, on the front of the flashcard you have the word “man”, and then you recall the story ("oh yes, the POWER 力 in the RICE FIELD 田”) and write the kanji out from memory: 男.

The controversial part is the suggestion that you should do all of this work - make up 2000+ mnemonic stories, and learn to handwrite each kanji from memory - before learning how to read (i.e. pronounce) any of the kanji.

In practice, most students will be studying Japanese at the same time. (Who’s using the Heisig method to learn kanji, but not also learning the Japanese language? Nobody, I reckon.)

Combining the Heisig method with Anki

Heisig’s book was first published in 1977, so he suggests using paper flashcards. But the method really comes into its own when you use it with a flashcard app. I’l talk about Anki here because it’s the app I used.

Anki is a flashcard app that uses the principle of spaced repetition to make practising with flashcards as efficient as possible. Put simply, spaced repetition means the app decides when you need to see a flashcard next, based on how recently you got it right.

I used Anki for years, both for vocabulary practice and for kanji writing practice. It’s actually the reason I got a smartphone, in 2011.

You can make your own flashcard decks (a “deck” is what Anki calls a set of cards) with Anki, or you can download decks that other people have made. I used a deck that someone else made, but I edited it a bit.

On the front of the each card, I had the Heisig keyword. In this case, Heisig’s keyword is “eat”. This is a good keyword, as the kanji 食 means “eating” or “foodstuff”, and 食べる (taberu) is a verb meaning “to eat”. So, the idea is that you see the word “eat” and have to remember how to write the kanji:

How this works in practice

I probably practised writing kanji like this every day for about 15 minutes, for about a year and a half in 2010-2011. Essentially, that’s how I learned to write Japanese.

And by learning the meanings of kanji, suddenly all those signs and labels all around me (I was living in Japan by this time) started to have meaning.

Outside my flat there was a sign with the word 歩行者 on it. I knew that 歩 meant “walk”, 行 meant “go”, and 者 meant “person”. That’s how I learned that 歩行者 means “pedestrian”. I didn’t know how to read it aloud, but I knew what it meant.

The school that I worked at was an eikaiwa gakkou, an English conversation school. On the front of the school was the word 英会話. I knew that 英 could mean “English”, 会 meant “meet”, and 話 meant “talk”. I also knew that the character 英 could be read as ei, because it was in the word 英語 (eigo, the English language). And that 話 could be read as wa, because it was at the end of 電話 (denwa, telephone). So from this I could guess that 英会話 was ei-something-wa… and I knew the word eikaiwa (English conversation), so I asked my boss if 英会話 was “eikaiwa” - yes.

I was vegetarian when I first moved to Japan, so I spent some time scouring packages in supermarkets to work out whether I could eat things or not. I knew that the radical 月 could mean “meat” or “flesh”, and I knew that 豕 meant “pig”, so I could guess that 豚 was probably “pork” or “pig”. I didn’t know the word for pig, or the word for pork. But I could guess that I probably didn’t want to eat something with 豚 in it.

In other words, the Heisig method works - when combined with other Japanese study.

(Incidentally, I don’t “teach” Heisig because it’s a bit weird, and not for everyone. But I don’t teach kanji through rote memorisation either. I use an integrated approach - I want students to learn the meaning of individual kanji, and the readings of whole words, and to learn kanji in context as much as possible. But I still think that Heisig is a great self-study method, and if you’re interested, you should check out his book*).

Post-Heisig

As my Japanese got better, I no longer associated the kanji with English keywords. When I saw the kanji 食 I’d think of the meaning - something to do with eating or food - but not necessarily Heisig’s keyword. So later, on the front of each card, I added an example word containing the kanji, which is written in hiragana. In this case, the word is たべる (taberu; to eat), and to test myself, I have to write out the word 食べる (i.e., not just the individual kanji):

I also have the stroke order on the back of the card, so that I can check straight away if the stroke order I wrote out is correct or not. I added these by screenshotting the stroke order diagram in takoboto, the dictionary app I use on my phone.

(I used to be a bit lazy about stroke order, but since I started teaching Japanese I have spent some time correcting my bad habits).

The stroke order diagram is good for checking that you’re handwriting the kanji in the correct way, too. A common mistake learners make is copying typeface fonts, but many kanji look quite different when handwritten to how they look in type.

In December 2019, I decided to dust off this (very neglected) Anki deck and do some handwriting practice, every day for a month. For twenty minutes every day, I’d go through flashcards and test myself on whether I could handwrite the kanji.

I really enjoyed the routine of practising kanji again. I find kanji practice surprisingly relaxing. I mentioned this to some students, and they (well some of them anyway!) said they find kanji writing practice relaxing, even meditative. Little and often is probably key.

Find something you enjoy, and do it every day forever

Years later, I was out for dinner with an American friend in Japan. We were looking at the kanji-filled handwritten menu, and I realised that his Japanese reading was really quick - much faster than mine. “How did you learn to read kanji?” I asked him.

“Er, I dunno. Just, reading books I guess? For, like, years.”

It probably doesn’t matter too much how you study kanji. To be honest, I’m not sure that the Heisig method is better than any other. It worked for me, but if you put the time in, there are other methods of learning kanji that might work just as well.

The key thing is to find something that works for you, and spend a little time on it every day. And if your friends laugh at you, try and ignore them! One day they might be asking you how you did it.

Related posts

Links

Links with an asterisk* are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

What is Shadowing and Can it Improve Your Spoken Japanese? I Tried Shadowing Every Day for a Month

“I can read it and understand it, but I can’t speak like that!”

…Does this sound familiar?

Almost all language learners feel that their production (speaking and writing) is not as strong as their comprehension (listening and reading). This is normal, but it’s still frustrating.

One method that is supposed to improve your listening and speaking is shadowing.

I’d heard of shadowing before, and I’d seen Japanese language learning resources devoted to it – but I’ve never tried it. I decided to try this every day for a month, and see what impact it had.

“I can read it and understand it, but I can’t speak like that!”

…Does this sound familiar?

Almost all language learners feel that their production (speaking and writing) is not as strong as their comprehension (listening and reading). This is normal, but it can be very frustrating.

One method that is supposed to improve your listening and speaking is shadowing.

I’m a Japanese teacher, but as a non-native speaker, I’m a Japanese learner too. I’m confident with my spoken Japanese, but like everybody I stumble over my words sometimes. And I’m aware that my spoken Japanese will never feel quite the same as my native language does.

Earlier in the year, while trying to speak Japanese every day for a month (without being in Japan), I went on a deep dive into Japanese pitch accent.

(Pitch accent In brief: Japanese has high-low tones, and pronouncing a word with the wrong pitch accent pattern makes you sound unnatural.)

I started watching the fantastic “Japanese Phonetics by Dogen” series on YouTube. Dogen recommends two key ideas to improve your spoken Japanese:

1) Record yourself and listen back to the recording, checking for speech errors

2) Practise shadowing every day

I’d heard of shadowing before, and I’d seen Japanese language learning resources devoted to it – but I’ve never tried it. I decided to try this every day in March, and see what impact it had.

I was hoping to improve my phonetic awareness (like most non-native speakers, I had never explicitly learned Japanese pitch accent before this). I also hoped that shadowing practice would work a bit like warm-up exercises to speaking, allowing me to speak more quickly without losing accuracy.

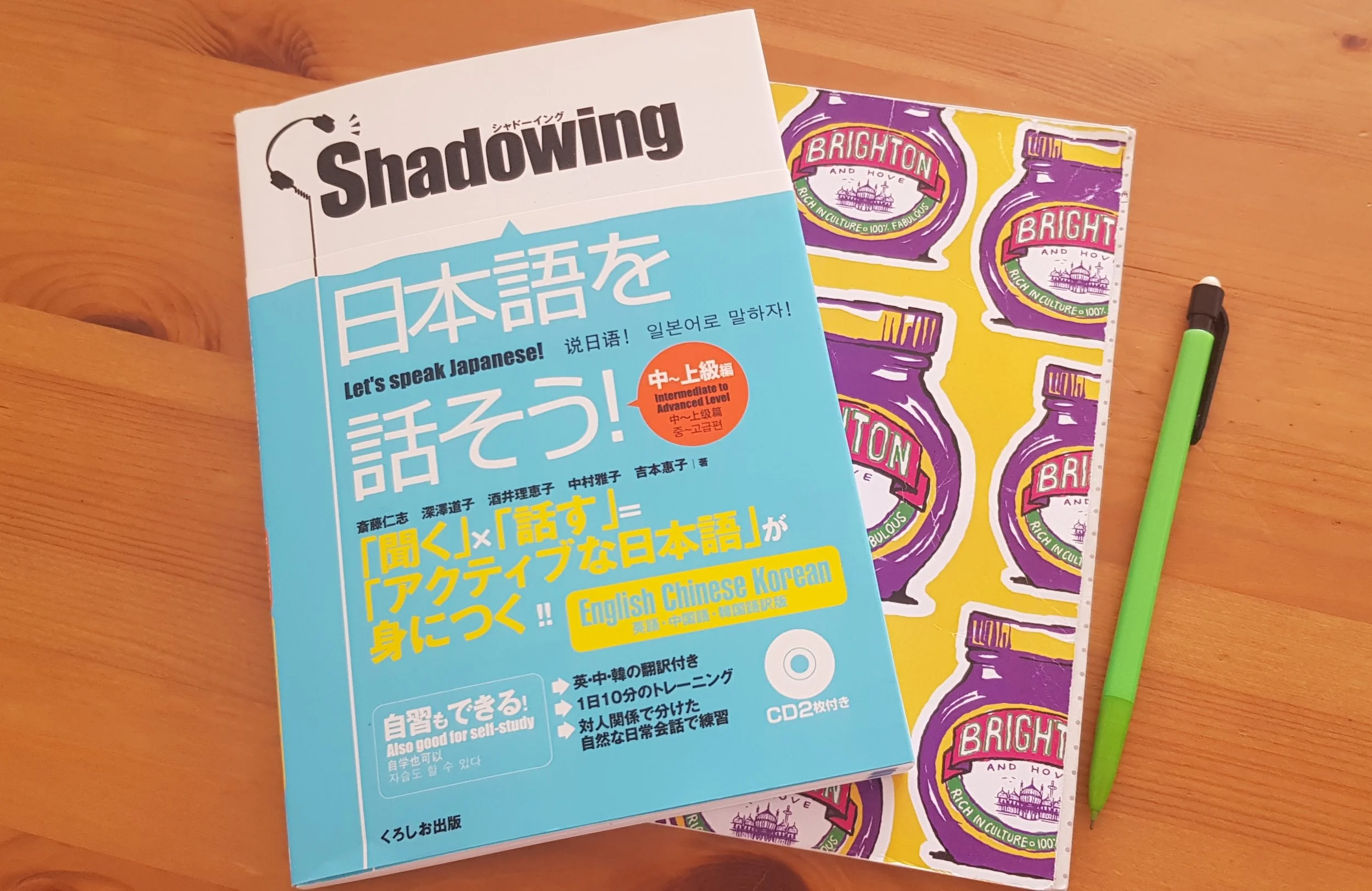

I didn’t have to look far to find a great shadowing resource – there is a popular book and CD combo called Shadowing: Let's Speak Japanese. It comes in two levels - beginner/intermediate, and intermediate/advanced. I ordered the latter from Amazon Japan, and followed the directions in the book. Every day for a month!

What is shadowing?

Most people are familiar with “listen and repeat” in language learning contexts. You listen to a conversation line-by-line and repeat each sentence after the recording.

Shadowing is different from simple “listen and repeat” in that you start speaking while the person on the audio is still talking. You echo the speaker 1 or 2 seconds after they speak, and talk over them.

If you tried to do this with long-form listening materials, even in your native language, it would be impossible – you’d get lost. And you wouldn't gain much phonetics or speaking practice by doing this.

So in shadowing, you use very short passages. The goal is to be able to produce the dialogue with perfect pronunciation, as close to the recorded audio as possible.

To do that, we need to break the process down into steps.

The book I bought was quite prescriptive, which at first seemed intimidating but in practice I found very helpful.

It suggests practising shadowing for 10 minutes a day, and doing one section o of the book (about 10 short conversations of about 4-5 lines each) continuously for 2-3 weeks.

So that’s what I did, following this process from the book to the letter.

How to do shadowing - step by step:

1) Find material at the right level for shadowing. Specifically, choose a short dialogue that is easy to read and understand, but difficult to say with fluency.

[Note from me (Fran): If you already have a Japanese textbook you’re using, you don’t need to buy a separate shadowing book. Use the short dialogues in your textbook.]

2) Listen to the audio and/or read the script, checking that you understand the conversation and looking up any words or expressions you don't know. You’re going to be repeating this conversation over and over, so it’s important that you understand what you’re saying, or the exercise is pointless.

3) Listen to the script and follow along with your finger.

4) Listen to the script and repeat the dialog in your head, without vocalising. That’s right – without speaking or moving your lips, silently repeat the dialogue a few seconds after the speaker.

5) Listen while visually following the script, and say the dialogue aloud a few seconds after the speaker. You’ll be talking over them.“The objective…is to keep up with natural speed, so think of it as a work out for your mouth when you practise.”

6) Without looking at the script, play the audio and say the dialogue aloud a few seconds after the speaker.

7) Without using the script, shadow the audio while thinking about the meaning of the conversation. Think about the emotions of the people in the conversation and the context.

Shadowing moves words and phrases from your passive to your active vocabulary

I followed a few steps from this process every day for at least 10 minutes. In a month, I did two sections of the shadowing book.

That’s not very much, really – 25 or 30 short conversations. But I felt like the words and phrases wormed their way into my spoken Japanese.

Here are a few examples:

1) I was talking to a friend about British weather, and the word 土砂降り(doshaburi, downpour) came out of my mouth. I’ve seen, heard and read that word before. But I don't think it’s ever been a part of my active spoken vocabulary.

2) I went for coffee with a Japanese friend and we were talking about something I feel quite sceptical about, when the phrase そうかな… (sou ka na? “I don’t think so?”) popped out of my mouth. Again, I’ve heard Japanese people say that phrase. But I don't think I’ve ever actually said it before.

Shadowing moved these words from my passive vocabulary into my active vocabulary. I kind of own them now – they’re part of my speech.

This shows how important it is to choose shadowing material that fits the way you want to speak. And it’s a good example of why you probably shouldn't shadow anime, unless you want to sound like a pirate or a robot cat.

Record yourself!

I also watched about half of Dogen’s Japanese Phonetics series on YouTube and made notes. I started to get into the habit of looking up the pitch accent of words I wasn't sure about.

And I recorded myself speaking, and listened back to it, comparing it line by line to the recording.

Like most people, I don't even like listening to recordings of myself in my native language. So listening to myself speak Japanese was quite painful. But I definitely noticed speaking habits I have that I didn't know I had, and little mistakes I didn't know I was making.

The downside of recoding yourself (as opposed to just shadowing) is that recording yourself and listening back to it takes about three times as long as just shadowing would.

Give it a go!

I found it easier to speak over the dialogue wearing headphones. But because shadowing involves talking to yourself, you can’t really do it on public transport. That being said, I found it relatively easy to squeeze 10 minutes of practice into my day. I did it before work, or afterwards when I got home.

Shadowing has its critics (if you want to read more about that, google “does shadowing work?”). But if you want to improve your spoken Japanese, I really recommend that you give it a try. I feel like it worked for me. Maybe it’ll work for you too?

Like me, you might find your vocabulary for British weather expanding! Or you might learn a new way to be sceptical. Same thing really.

Links:

Amazon links with an asterisk* are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you, when you click through and buy the book. Thanks for your support!

Japanese Phonetics by Dogen https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jakXVEUTT48 (some of these fantastic videos are free; the complete series is available to Dogen’s Patreon supporters)

Shadowing: Let's Speak Japanese! Beginner to Intermediate (Book & Audio CD) https://amzn.to/2XSzW0H *

Shadowing: Let's Speak Japanese! Intermediate to Advanced Level (Book & Audio CD) https://amzn.to/2XQCwEk *

Please note that both books are likely to be slightly cheaper on Amazon Japan:

シャドーイング-日本語を話そう-初〜中級編 https://www.amazon.co.jp/シャドーイング-日本語を話そう-初〜中級編-斎藤-仁志/dp/4874243541/

シャドーイング-日本語を話そう-中~上級編 https://www.amazon.co.jp/シャドーイング日本語を話そう-中~上級編-斎藤仁志;深澤道子;酒井理恵子;中村雅子;吉本惠子/dp/4874244955/

Japanese guys don’t want your Valentine’s Day chocolate anyway

ハッピーバレンタインデー! Happy Valentine's Day!

Valentine's Day in Japan is pretty different from the U.K. There's honmei choko (chocolate for someone you're into), giri choko (obligation chocolate), and even tomo choko (chocolate for friends)...

And a month later there's White Day to contend with…

ハッピーバレンタインデー! Happy Valentine's Day!

Valentine's Day in Japan is pretty different from the U.K. There's honmei choko (chocolate for someone you're into), giri choko (obligation chocolate), and even tomo choko (chocolate for friends)...

And a month later there's White Day to contend with…

One survey revealed that 90% of Japanese men said they didn't care about getting Valentine's Day chocolate, and wished women wouldn't bother.

Click here to read an article I wrote for SoraNews24 on the subject.

(It's from a couple of years ago, but I think it's still super relevant... especially on Valentine's Day).

New Year's Resolutions - 2018

明けましておめでとうございます! (Akemashite omedetou gozaimasu!) Happy New Year!

Did you make any New Year's Resolutions this year?

January is a really good time to think about goals for the year ahead. Apart from anything else, it's cold! And it's nice to be inside making plans.

Here are my New Year's Resolutions for 2018…

明けましておめでとうございます! (Akemashite omedetou gozaimasu!) Happy New Year!

Did you make any New Year's Resolutions this year?

January is a really good time to think about goals for the year ahead. Apart from anything else, it's cold! And it's nice to be inside making plans.

Here are my New Year's Resolutions for 2018:

1) blog once a week

This one is easy (I hope!) and a continuation of last year.

In 2017 I aimed to publish a blog post a week. I actually did 26, which is one a fortnight.

That's not bad, but I definitely want to beat that in 2018.

2) play more games

In class, I mean. I want to work on making classes more fun, and one easy way to do that is more games.

My lovely students playing fukuwarai ("Lucky Laugh") game ↓

When we laugh together, we learn together.

(Cheesy but true).

3) read every day

This is a personal one. Last year I tried to read more Japanese fiction, and kind of failed.

I did find, though, that once I actually start reading I'm ok. It's the getting started that's the tricky part.

This year, I'm going to read some Japanese fiction every day, and keep a note in my 5-year diary when I've done it.

(16 days in, this is going pretty well.)

4) go to more teaching events

This year, I'm planning to go to more Japanese teaching and education-related events in London.

I went to a couple recently - a Japanese grammar teaching workshop at SOAS, and a bunch of seminars at the Language Show London.

I found it super helpful to reflect on my teaching practice and discuss ideas with other teachers and linguists.

I definitely want to go to more events like this in 2018.

...and it's a good excuse to go to London for the day too.

5) track these goals

Waiting until the end of the year to see how your goals are going doesn't really work.

In 2017, I actually completely forgot about one of my resolutions (to watch more drama in class). I'm going to avoid that this time by pinning them above my desk.

I'd love to know what New Year's Resolutions you made. Let me know in the comments!

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.