Hi! This blog is no longer updated, but on this page you can find an archive of my blog posts, 2016-2022. Click here to view the blog index (a list of all posts).

For the latest news about Step Up Japanese, sign up to my newsletter.

Search this blog:

"Does Japanese Have Plurals?"

After the excitement of our first school Summer Barbecue, I spent the day in bed watching one of my favourite films in Japanese.

It wasn’t a Japanese film though. I watched Hot Fuzz (or to give its Japanese title ホット・ファズ -俺たちスーパーポリスメン "Hot Fuzz: We Are The Super-Policemen!")

Watching British comedies dubbed into Japanese might not be the "purest" way to listen to Japanese. But if you enjoy it, it's definitely worth doing. Dubbed films are easy to watch, too, assuming you've seen the film before and know the plot already.

Anyway, there's a little scene in the Hotto Fazzu dub that's a nice example of Japanese plurals in action, so I thought I'd share it with you.

After the excitement of our first school Summer Barbecue (back in 2017), I spent the day in bed watching one of my favourite films in Japanese.

It wasn’t a Japanese film though. I watched Hot Fuzz (or to give its Japanese title ホット・ファズ -俺たちスーパーポリスメン "Hot Fuzz: We Are The Super-Policemen!")

Watching British comedies dubbed into Japanese might not be the "purest" way to listen to Japanese. But if you enjoy it, it's definitely worth doing. Dubbed films are easy to watch, too, assuming you've seen the film before and know the plot already.

Anyway, there's a little scene in the Hotto Fazzu dub that's a nice example of Japanese plurals in action, so I thought I'd share it with you.

Angel and Danny are in the corner shop, and the shopkeeper asks them:

殺人犯たち捕まらないの?

satsujinhan tachi tsukamaranai no?

"No luck catching them killers then?"

"Killers" is translated as 殺人犯たち satsujinhan-tachi. You take the word 殺人犯 satsujinhan (murderer) and add the suffix たち (tachi) - which makes it plural.

See? Japanese does have plurals! ... when it needs them.

Danny doesn't notice the shopkeeper's slip-up (she knows more than she's letting on), and replies:

人しかいないんだけど。

hitori shika inai n da kedo.

"It's just the one killer actually."

PC Angel, of course, mulls over the shopkeeper's words, and realises their significance: there's more than one killer on the loose.

It's a turning point of the movie, and it rests on a plural. Yay!

You can use たち like this when you need to indicate plurality:

私たち watashi-tachi we, us (plural)

あなたたち anata-tachi you (plural)

ジョンたち jon-tachi John and his mates

It's not that common, but it does exist. Keep an eye out for it! You never know, you might just solve a murder case.

First published 8th Sept 2017

Updated 11th Dec 2020

What's the Difference Between Mina and Minna (And Why Does It Matter Anyway?)

If you watch Japanese TV or anime (or are paying attention in class) you've probably come across the Japanese word mina-san (皆さん) meaning "everybody".

But what's the difference between mina and minna? What's mina-sama all about? And ... does it actually matter?

Mina-san, konnichiwa! (皆さん、こんにちは ) Hello everybody!

If you watch Japanese TV or anime (or are paying attention in class) you've probably come across the Japanese word mina-san (皆さん) meaning "everybody".

But what's the difference between mina and minna? What's mina-sama all about? And ... does it actually matter?

1.皆さん Mina-san

Mina means "everybody", and it's commonly used with "-san" (the honorific suffix you put on the end of people's names to be polite).

Mina-san is often used when addressing a group of people, especially when they don't know either other too well or the situation calls for a slightly more formal greeting.

I find myself using mina-san in class a lot, which makes sense - I’m addressing a group of people.

As you might expect, Japanese YouTubers say “mina-san konnichiwa” a lot too ("hi guys!")

These example sentences from jisho.org should give you a good idea of the kinds of situation when mina-san is used:

2.みんな Minna

Also common is minna, which is just a spoken form of mina. Minna is more casual than mina.

Examples from jisho show us that people also use minna when they talk about everyone, as well as when addressing groups:

3. Beware! It’s not みんなさん minna-san

You can't mix them up and use minna-san though. That's incorrect.

Probably no one will mind or notice in a casual situation, but if you're trying to be polite, stick with mina-san. Or you can even go more polite with...

4. 皆様 Mina-sama

In more formal situations, the -san suffix is switched up to the more polite/formal -sama.

Mina-sama functions a lot like "ladies and gentlemen", or “esteemed guests”, and is used in writing, and in announcements:

Why does this matter?

Well really, which word you use is going to depend on the situation.

Mina-sama is super formal and it would sound weird if you use it with your friends. Likewise, minna is pretty casual and might not be appropriate in a business setting.

A lot of gaining fluency in a language is about choosing the right word for the right situation. The more examples you can read, and the more you can expose yourself to the Japanese language, the more these distinctions will start to make sense.

Mina-san, if you'd like to learn more Japanese with me, click here to check out my new online Japanese language courses!

First published 9th June 2017

Updated 7th April 2020

Why Does The Japanese Language Have So Many Alphabets?

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

My students ask a lot of good questions. And one that sent us off on a bit of a tangent a few weeks ago was: “how old is Japanese writing?”

So, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of Japanese history with a very brief introduction to the Japanese writing system!

Until the 1st or 2nd century, Japan had no writing system. Then, sometime before 500AD, kanji - Chinese characters - made its way to Japan from China (probably via Korea).

These characters were originally used for their meaning only - they weren't used to write native Japanese words.

↓ And at that time, Japanese writing looked like this. Look, it looks like Chinese!

(Image Source - Nihon Shoki, Wikipedia)

But it was inconvenient not being able to write native Japanese words down, and so people began to use kanji to represent the phonetic sounds of Japanese words, not only the meaning. This is called manyougana and is the oldest native Japanese writing system.

For example, in manyougana the word asa (morning) was written 安佐 (that's a kanji for the “a” sound - 安 - and another for the “sa” sound - 佐). These characters indicate the sound of the word - “asa” - but not its meaning.

In modern Japanese we'd use 朝, the kanji that means "morning" for asa. This character shows its meaning AND its sound.

The problem was, manyougana used multiple kanji for each phonetic sound - over 900 characters for the 90 phonetic sounds in Japanese - so it was inefficient and time-consuming.

Gradually, people began to simplify kanji characters into simpler characters - that's where hiragana and katakana came from.

Katakana means "broken kana" or "fragmented characters". It was developed by monks in the 9th century who were annotating Chinese texts so that Japanese people could read them. So katakana was really an early form of shorthand.

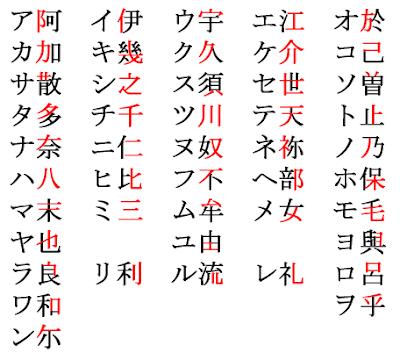

Each katakana character comes from part of a kanji: for example, the top half of the kanji 呂 became katakana ロ (ro), and the left side of the kanji 加 became katakana カ (ka).

↓ Each katakana comes from part of a kanji.

(Source - Katakana origins, Wikipedia)

Women in Japan, on the other hand, wrote in cursive script, which was gradually simplified into hiragana. That's why hiragana looks all loopy and squiggly. Like katakana, hiragana characters don't have meaning - they just indicate sound.

↓ How kanji (top) evolved into manyougana (middle in red), and then hiragana (bottom).

(Source - Hiragana evolution, Wikipedia)

Because it was simpler than kanji, hiragana was accessible for women who didn't have the same education level as men. The 11th-century classic The Tale of Genji was written almost entirely in hiragana, because it was written by a female author for a female audience.

Modern Japanese writing uses all three of these “alphabets” - hiragana, katakana, and kanji - often all mixed up in the same sentence.

What would 12th-century people in Japan think of my students, 900 years later, learning hiragana as they take their first steps into the Japanese language?

First published 28th Oct 2016

Updated 27th Jan 2020

How Do I Know if a Group Language Class is For Me?

If you’re thinking about taking Japanese lessons, one of the first things you’ll have to decide is whether you want to join a group class, or take one-to-one lessons.

There are pros and cons to all methods of learning a language. Here, I’ll look at some of the key advantages of joining a group.

If you’re thinking about taking Japanese lessons, one of the first things you’ll have to decide is whether you want to join a group class, or take one-to-one lessons.

There are pros and cons to all methods of learning a language. Here, I’ll look at some of the key advantages of joining a group.

1) Meet other language learners

Classes give you access to a teacher, but a group class also provide you with an instant group of other people with the same interest as you.

You can speak in your target language together, go out for dinner and order in Japanese, and message each other asking "what was last week's homework again?"

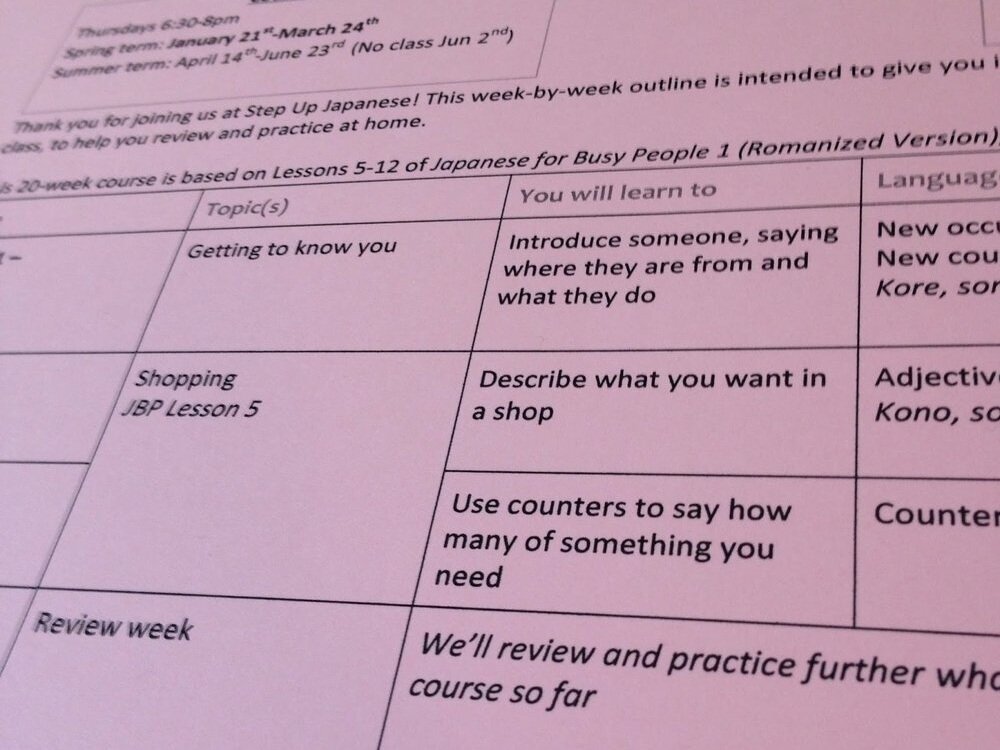

(Just kidding - thanks to the course outline I'll provide you with, you'll always know what this week's homework is.)

In a group class, students can support and help each other. It's obvious to me that my lovely students gain a lot from each others' support!

2) Keep a regular schedule

To gain any skill, you need to practice regularly. The great thing about having class on a regular day is it forces you to practice. Unlike exclusive self-study where you'll always have an excuse to procrastinate, weekly classes require you to be prepared for every class so you can get the most out of it.

Practice makes perfect, after all.

3) It's your class

You might feel like the only way to get a class tailored to your needs is to take one-to-one lessons. But a good group class - especially one for a small group of students - should be tailored to the students in it as much as a private lesson would be.

That's why I ask my students to give me regular feedback (informally, and through anonymous questionnaires) about how class is going and where you want it to go next.

It's your class, not mine, and we can focus on what you want to focus on.

That doesn't mean I'm going to do the hard work for you. If you want to get good at Japanese, you'll need to find ways of practicing and exposing yourself to the language as much as possible outside of class too.

But a group class can provide the basis of your knowledge, a structure to work with, and a group of friendly faces to answer your questions.

It also gives you a great excuse to go to that great Japanese restaurant again with your classmates.

First published June 2016; updated 9th January 2020.

Japanese Loanwords From Languages That Aren't English

Modern Japanese contains a lot of loan words - words that Japanese has “borrowed” from other languages. These words are typically written in the katakana “alphabet”.

Many of these words come from English - but not all.

Modern Japanese contains a lot of loan words - words that Japanese has “borrowed” from other languages. These words are typically written in the katakana “alphabet”.

Many of these words come from English - but not all.

So if you’ve been wondering what happened to the “t” sound at the end of the Japanese word resutoran (レストラン, restaurant), it was never there in the first place - because that loanword didn’t come from English. It came from French.

And my students sometimes ask me why the Japanese word for salad is sarada (サラダ), not “sarado”. That’s because sarada comes not from the Engish word “salad”, but from the Portuguese “salada”.

It’s good to know which loanwords didn’t come from English - and it's interesting to know what languages they come from - so you can remember how to pronounce them correctly.

Hopefully this will help you remember that it’s resutoran (not resutoranto!)

Quiz time!

How many of these Japanese loanwords do you know? Can you guess the meaning of any?

Rentogen レントケン

Piero ピエロ

Arubaito アルバイト

Piiman ピーマン

Ruu ルー

Esute エステ

Ikura イクラ

Noruma ノルマ

Karuta カルタ

Sukoppu スコップ

Igirisu イギリス

⇩ HINT: Japan believes in calling a スコップ a スコップ

The Answers:

Rentogen レントケン X-ray (from German)

Piero ピエロ clown (French)

Arubaito アルバイト part time job (German)

Piiman ピーマン peppers [the vegetable] (French)

Run ルー roux sauce [or, more commonly, a block of Japanese curry mix used to make curry sauce] (French)

Esute エステ aesthetic salon i.e. beauty salon (French)

Ikura イクラ salmon roe (Russian)

Noruma ノルマ quota (Russian)

Karuta カルタ Japanese playing cards (Portuguese)

Sukoppu スコップ spade (Dutch; Flemish)

Igirisu イギリス the U.K. (Portuguese)

Pan パン bread (Portuguese)

So, next time you see a katakana word you don't recognise, don't despair - it might not have originated from a language you speak!

First published May 2016

Updated 9th Jan 2020

Is it Shinbun or Shimbun?

It’s both. And it’s neither.

Beginner students often ask whether “shinbun” or “shimbun” (the word for “newspaper” in Japanese) is correct.

You’ll see both spellings...and books about the Japanese language don’t seem to be able to agree either.

If you look at the two most popular Japanese beginner textbooks, Genki has “shinbun”, whereas Japanese for Busy People has “shimbun” and also “kombanwa”.

But why?

It’s both. And it’s neither.

Beginner students often ask whether “shinbun” or “shimbun” is the correct spelling of the word for “newspaper” in Japanese.

You’ll see both spellings… and books about the Japanese language don’t seem to be able to agree either.

If you look at the two most popular Japanese beginner textbooks, Genki has “shinbun”, whereas Japanese for Busy People has “shimbun” and also “kombanwa”.

But why?

Well, there are different ways of writing Japanese in romaji (roman letters i.e. the alphabet). All romaji is an approximation, and there are two different major systems, both used widely.

In elementary school, Japanese kids learn Kunrei, the government’s official romanization system. Kunrei is more consistent, but not particularly intuitive for non-Japanese speakers.

In the Kunrei system:

しょ is written as “syo”

こうこう is written as “kookoo”

But textbooks for people learning Japanese tend to use the Hepburn system, which is easier for non-native speakers. Modernised Hepburn writes しょ as “sho” and こうこう as “kōkō”.

"N or M?"

Under the older Hepburn system of romaji, a ん (n) before a "b" or "p" sound used to be written as m. This gave us romaji spellings like shimbun and sempai. (The Kunrei system, on the other hand, never used this rogue "m" at all).

When Modernised Hepburn was introduced in 1954, the "m" rule was dropped. Since 1954, both major systems have said that these words should be written as shinbun and senpai.

So shimbun-with-an-m hasn't been officially used since 1954...but it is still the preferred romanization of several major Japanese newspapers: Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun.

So it seems like shimbun-with-an-m is still with us.

"So which is better?"

Arguably, “shimbun” is closer to the pronunciation of the word. There IS a sound change going on here – before a “p” or “b” sound in Japanese, the ん sounds more like “m” than “n”.

But "shinbun" is more consistent, and personally I prefer it - especially if you’re still learning kana.

There is no ‘m’ hiragana, and I don’t want you wasting your time looking for it on your kana chart.

"Which is more common?"

I don’t know. But it kind of doesn’t matter which one is more common: the Japanese way to write the word for newspaper isn't “shinbun” or “shimbun”. It’s not really even しんぶん. The Japanese word for newspaper is 新聞.

Which brings me neatly onto my next question...

“Why are you writing it in romaji anyway?"

Some people say that the shimbun/shinbun thing is a slightly pointless question. Everyone should just learn the kana, and then we wouldn't have this problem, right?

But romaji isn’t just read by people learning Japanese. Romanised stations and place names and even people's names are read by millions of people visiting Japan who don’t know Japanese.

And for people who don’t speak Japanese (especially English speakers), it's easier to guess the pronunciation of “shokuji” than “syokuzi”.

So, while the current system is a bit of a muddle, it's the best thing we've got. I think we can all agree on that.

(First published February 12, 2016. Updated June 21, 2019)

What’s the difference between sensei and kyōshi?

The word "sensei" is pretty well-known even among people who don't speak Japanese, but did you know that you shouldn't use sensei about yourself?

Here's what the textbook has to say:

"Use 'kyōshi' for yourself and the respectful 'sensei' for another person."

That's a pretty good starting point. But there's a bit more to it than that.

Japanese has (at least) two words for "teacher".

The word "sensei" is pretty well-known even among people who don't speak Japanese, but did you know that you shouldn't use sensei about yourself?

Here's what the textbook has to say:

"Use 'kyōshi' for yourself and the respectful 'sensei' for another person."

That's a pretty good starting point. But there's a bit more to it than that.

1. Kyōshi = school teacher

Kyōshi means the academic kind of teacher, someone who teaches in a school:

(私は)高校の教師です。

(watashi wa) kōkō no kyōshi desu.

I'm a high school teacher.

Images: Irasutoya

2. Sensei is a title

Sensei, however, is a respectful title, and should be used when talking about other people:

彼は中学校の先生です。

kare wa chūgakkō no sensei desu.

He's a junior high school teacher.

Watashi wa sensei desu is best avoided.

3. Sensei = master

Sensei can also be used more generally for a person who teaches something.

People who teach flower arranging or martial arts, for example, are sensei:

お花の先生

ohana no sensei

flower-arranging teacher

空手の先生

karate no sensei

karate teacher

茶道の先生

sadō no sensei

teacher of tea ceremony

If you're talking about yourself, however, you still shouldn't go around calling yourself sensei.

You can use the verb 教える oshieru (to teach) instead:

(私は)お花を教えてます。

(watashi wa) ohana wo oshiete imasu.

I teach flower arranging.

Certain types of professionals such as doctors or lawyers are also sensei (but again, not kyōshi).

4. "Sensei!"

Sensei is attached after teachers' names instead of san:

山本先生

Yamamoto Sensei

= Mr/Ms Yamamoto; “Yamamoto teacher”

It's pretty common to drop the name, too, and just call your teacher sensei:

先生、おはようございます!

Sensei, ohayō gozaimasu!

“Good morning, teacher”

So to summarise:

Use '“kyōshi” for yourself and the respectful “sensei” for another person.

“Sensei“ is not just for teachers, but also for masters of other skills, and for doctors

Affix “sensei” to your teacher’s name to show respect